50 STATES OF FOLK: All Roads in Jazz Lead Back to Louisiana’s Congo Square

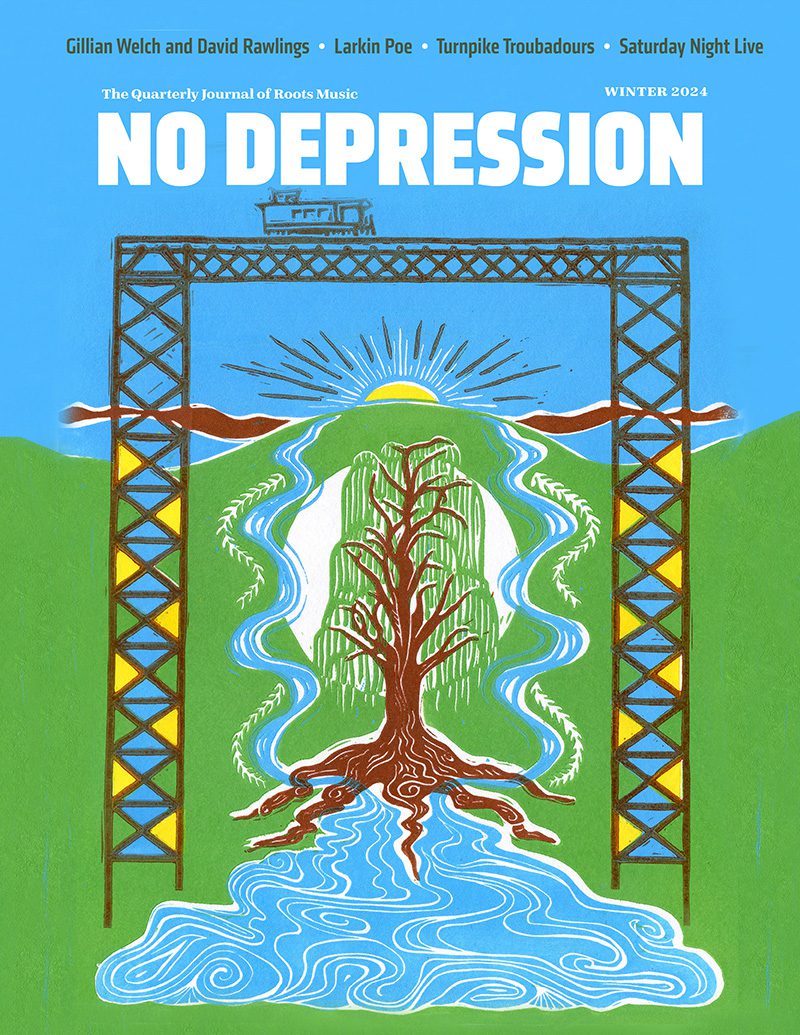

New Orleans' Congo Square (photo by Rebecca Todd / Getty Images)

This series was established with the goal of revealing the hidden histories of American music. But I doubt you’ll be surprised to learn that the heart of jazz is largely in New Orleans.

However, you may be surprised to learn just how specific that birthplace is. Jazz was not only born in New Orleans. It was born in one plot of land just north of Rampart Street, known as Congo Square.

Le Code Noir and the Birth of Congo Square

In 1718, the city of New Orleans was founded. Just one year later, the first slave ship from Africa would make port there.

By 1724, the Code Noir was put into law in Louisiana. This set of laws—based on earlier codes developed in the French Caribbean colonies—was meant to regulate the behavior of enslaved people, Native Americans, and free people of color living in Louisiana. This code provided the enslaved population of the territory with some rights, including requiring slave-owning whites to baptize them into the Catholic faith and to give them Sundays off work in order to worship.

While it granted more rights to slaves than in the American territories in some ways, French colonial slavery was still a brutal system in which to be imprisoned. And the slave-owning classes running New Orleans knew they had to keep it that way in order to continue extracting the labor necessary to build a glittering city on a swamp. Giving enslaved Africans time off was a calculated risk—one that was balanced by not allowing them to congregate outside of church. However, despite constant threats and crackdowns, informal gatherings almost immediately began to take hold. In remote and public places, the enslaved people would cook, dance, and sell goods to each other, thereby mixing and mingling with the many cultures of their fellow slaves—people from the Caribbean, Latin America, France, Spain, and tribes all over Africa.

Eventually, the white leadership of New Orleans recognized that they couldn’t prevent the enslaved population from gathering, so they decided to tightly regulate it. In 1817, Mayor Augustin de Macarty issued a decree restricting gatherings of enslaved people to an open plot between St. Anne and St. Peter streets. Eventually, this plot would come to be known as Congo Square.

The Musical Impacts of Congo Square

Randy Fertel, a writer and philanthropist with a specialization in New Orleans history, noted that “there are several places that are considered the birthplace for jazz, but the real roots are at Congo Square.” At the market established there, they were allowed not only to sell each other their wares, but also to play music. They could use their native instruments. They could play drums, dance, and sing.

In this melting pot of cultures, the building blocks of jazz were in place. You had call-and-response rhythms, syncopated beats, and the habanera rhythm of which Jelly Roll Morton once proclaimed, “If you can’t manage to put [the habanera] in your tunes, you will never be able to get the right seasoning […] for jazz.” Over time, as the enslaved Africans became more and more exposed to European culture, elements of European style began to tinge the music of Congo Square.

One such example is the iconic Second Line marches of New Orleans. Following the abolition of slavery and the end of the Civil War, Black musicians were hired to play in the regimented, military-style brass bands in town. With the contemporary popularity of the sousaphone to fill in the bass line of the band, these bands could now move. Black musicians began to experiment with the brass band format, taking it into the streets and adding in the traditional rhythms that they’d been playing for decades in Congo Square and for centuries before in their ancestral homes across the globe.

This soon evolved into what is now known as the “Second Line,” when Black musicians incorporated their new marching band format into their traditional funeral practices of honoring the dead by marching behind the funeral procession. These bands would play a broad range of music, spanning from mournful spirituals to upbeat brassy tunes — turning one family’s mourning into something that the whole community could share in.

Impacts Today

You don’t need me to tell you how influential jazz and African-American music have been to American culture—and, frankly, to all pop culture worldwide. The syncopated rhythms pioneered by enslaved Africans living in America not only gave us jazz—they also gave us the blues, soul, swing, bluegrass, rock and roll, and more. That influence can be heard everywhere, as all of those genres have influenced each other and as musicians listen across genres and hone their own unique musical voices. There are direct lines to Congo Square not just in the marching brigades of New Orleans, but also at every community swing dance, every Black church service, and in every DJ’s turntable. It is a testament to the power of the human spirit, and the unstoppable force of personal connection, that we continue to honor the original dancers, musicians, and merchants of one tightly regulated corner of New Orleans more than 200 years later.