Overwhelmed by a confluence of crises, Justin Vernon retreats to a Wisconsin cabin and records Bon Iver’s 2007 debut, For Emma, Forever Ago: a set of melancholy, austere, and melodically haunting songs replete with acoustic guitars, textural vocal arrangements, and minimal / lo-fi production. The album occasionally references Nick Drake’s Pink Moon, Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, and Beck’s Sea Change; however, is more ostensibly a key contribution to a 1990’s / early 2000’s indie-folk wave that includes Elliott Smith’s oeuvre, Sufjan Stevens’ Seven Swans, Fleet Foxes’ eponymous debut, and Iron & Wine’s Our Endless Numbered Days.

Bon Iver’s follow-up EP, Blood Bank (2009), rather than fleshing out the traditional elements inventively navigated in For Emma, features Vernon exploring the rudiments of electronica, the four-song release a notable experiment in musical reinvention. Most striking is the concluding track, “Woods,” with its stark soundscape and uber-topical use of the vocoder. In this sense, the Dylan reference may be additionally relevant. As Dylan embraced what was most pressingly au courant in his age (electric music), so Vernon embraces the salient paradigm of his: digital nuancing and a consummate employment of recording and production options. And yet, as Dylan’s songwriting remained characteristically Dylan’s (the songs on 1964’s Another Side of Bob Dylan share a continuity with the songs on 1965’s Bringing It All Back Home, even if the musical contexts vary, sonically and energetically), so the Justin Vernon of For Emma is recognizable in Blood Bank, despite the songs on the latter album being written, perhaps, with different treatments in mind; indeed, perhaps the treatments are part and parcel of the compositional process. At any rate, still prominent are Vernon’s memorable falsetto, oblique lyricism, and impeccable sense of melody; i.e., Vernon’s songwriting is never eclipsed by digital applications; the emotional content of the album is complemented by Vernon’s utilization of the studio, never replaced by it.

Ditto his second full-length release, Bon Iver Bon Iver (2011). If Blood Bank represents Vernon’s initial romp in the domain of electronic folk, this album shows him mining the possibilities more vigorously. He certainly draws inspiration from Bjork; most apparently, the albums Homogenic, Vespertine, and Medúlla, the Icelandic’s nuanced voice bathed in a variety of digital textures. Vernon’s chief muse, however (then and now), may be Radiohead, a band that’s forged a career out of fusing the digital and traditional, the stark and maximal, the delicate and sublime. It may be worth further noting (speculating?) that throughout the history of recorded music, the projects that reflect mastery have featured fresh iterations of unity, artists alchemizing contradictory elements into paradoxical gestalts: Springsteen’s late-career synthesis of two signature styles—the rollicking Romanticism of “Born to Run” and the stripped-down balladry of a song like “Wreck on the Highway”—on 2012’s Wrecking Ball. Joni Mitchell’s intricate guitar work, delicate but soaring voice, and dire content on Blue. The despair and bliss, harmony and cacophony, of Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. Point being: Vernon has studied the canon; more importantly, is motivated, in his own way and via his own organic methods, to achieve a significant reconciliation of opposites.

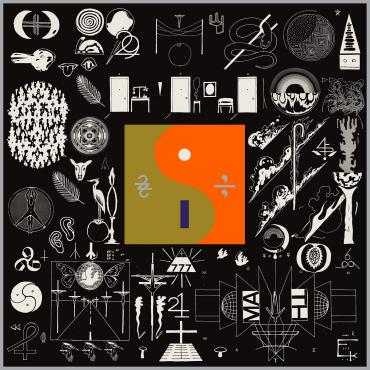

With his new album, 22, A Million, Vernon further hones his skills as a songwriter, sonic architect, and producer. Esoteric titles—references to math and numerology—conjure images from Darren Aronofsky’s nihilistic Pi, Max Cohen ambling down gray streets or hunched over his machine, madly calculating, programming, deciphering. Songs that wouldn’t be out of place on Duncan Jones’s Moon reveal Vernon moving further from his folk (For Emma) roots; or, more aptly, expanding the genre of folk in fertile directions. The opening track, “22 (OVER S∞∞N),” establishes the tone of the album, a funereal starkness reminiscent of passages from Pink Floyd’s Final Cut. Also included are samples from Mahalia Jackson’s “How I Got Over” and a jazzy sax segment, both of which are particularly evocative, grounding the album in accessible sounds while highlighting Vernon’s ability to blend disparate elements into a cogent whole.

On track three, “715 – CRΣΣKS,” Vernon effectively utilizes the vocoder (the effect more central to the song than on the abovementioned “Woods” from Blood Bank), informed by Laurie Anderson as well as contemporaries Frank Ocean and Kanye West:

low moon don the yellow road

i remember something

that leaving wasn’t easing

all that heaving in my vines

“33 “GOD,” with its hummable melody, is one of the more immediately accessible songs on the album. Included are several well-placed samples, including from Sharon Van Etten’s “Dsharpg.” Vernon’s oblique lyrics, rarely delivering a direct message or sentiment, evoke a mix of emotions, from sadness to anxiety:

is the company stalling?

we had what we wanted

your eyes

with no word from the former

i’d be happy as hell, if you stayed for tea

“666 ʇ” makes use of stark instrumentation and nuanced sampling, including from Dave Kingsby’s “Standing in the Need of Prayer.” Rhythms are both recognizable and percussively alien. Vernon balances the accessible and the unfamiliar, again combining potentially discordant elements to forge a compelling gestalt.

Throughout this album, we witness Vernon’s epic quest for meaning, his yearning to understand the root causes of suffering, a journey that might resonate with Homer or the Buddha: “not sure what forgiveness is / we’ve galvanized the squall of it all / i can leave behind the harbor.”

With the final track, “00000 Million,” Vernon offers a fitting lyrical conclusion: “must have been forces / that took me on them wild courses / who knows how many poses that i’ve been in.” And: “the days have no numbers.” The song ends abruptly: “it harms me / it harms i’ll let it in,” a musical and thematic truncation.

22, A Million is not so much a continued departure from Bon Iver’s earlier work as a further refinement of what was offered in more spontaneous and perhaps inchoate form on For Emma. With 22, A Million, we witness the completion of a standout superfecta—an album that both integrates the high points of Bon Iver’s first three recordings and illustrates Vernon’s continued foray into the broad realms of songwriting and production: his most focused and ambitious permutation to date.