Miranda Lambert – Nashville Lone Star

Just lately, in the weeks before our conversation, she’d been opening for Dierks Bentley, who headlines at big venues now, playing music that continues to bridge the gap between mainstream country and Americana — the gap that once seemed such a chasm.

And so, yes, this young Texas singer, the author of songs that are not production-line mainstream country issue by anybody’s standards, and who only a few years ago just stood still and strummed, has been paying attention.

“Dierks should be a headliner,” says Miranda Lambert, 23. “He’s such a good entertainer. I’m just a few years behind him. I’m watching every move he makes, thinking ‘OK, let’s see what he’s doing on tour today.’ I want to see where I’ll be in two years, follow in his footsteps, see what works, what doesn’t, where this crowd was good, this wasn’t — learn the ropes.

“You know, I hadn’t planned on being an entertainer that way at all until the last couple of years.”

But just standing still at the microphone is not a wise approach when you want to win over rowdy crowds at stadium-size venues, or in the midsize halls and bars where, more and more, Lambert can headline on her own. She is also coming to be known for fiery, electric shows, even as her first big-label album, Kerosene, has gone platinum.

“I guess I’ve kind of put myself in this niche of ‘rocker chick,'” Lambert says, with some evident wonder, “though I never thought of myself that way — ever.”

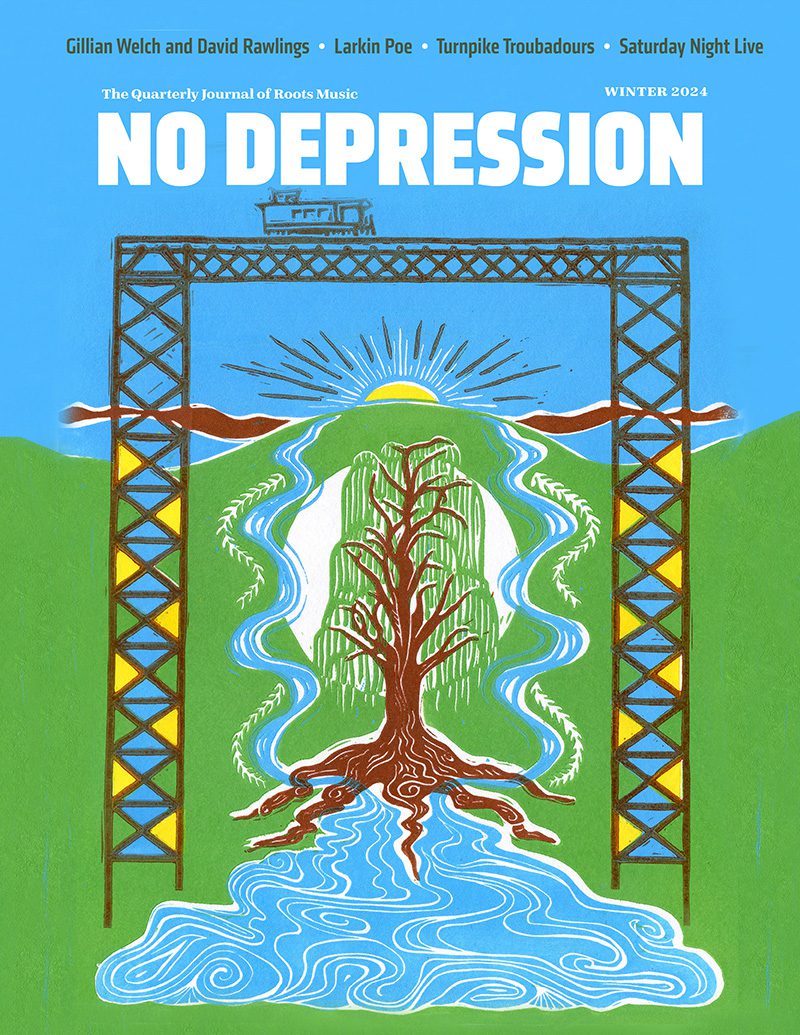

Her new disc, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, has its necessary share of hooky, sometimes rocky, radio-friendly, mainstream country single material — but also includes songs written by Gillian Welch & David Rawlings (“Dry Town”), Patty Griffin (“Getting Ready”), and Carlene Carter & Susanna Clark (“Easy From Now On”).

So add that up: This Texan rocks, and she turns to songs like those to record along with her own compositions (Lambert has eight with her name attached on the new record; she wrote or co-wrote eleven of the twelve songs on Kerosene). And her material sounds like it belongs in that company.

A decade ago, Lambert’s chances of charting in mainstream country as an unproven artist-songwriter, or even of being signed as a singer, would have been close to nil. Today, she’s having enough success that she’s already opened doors for others with the old alternative tinge. The Wreckers’ odds of being signed before her success, let alone charting in mainstream country, would have been about as high as Austin’s great, ghettoized all-female group the Damnations.

Things have changed. And Lambert is more than aware of the implications of her own success, its significance as another step in the real expansion of the possibilities for mainstream country music in this surprising decade. She alludes to Big & Rich playing with the introduction of hip-hop sounds; to Gretchen Wilson reintroducing the tough, knowing, working-class songwriter (a Loretta kind of woman) to a star level that had seemed reserved for Hollywood types; to Josh Turner starring as a contemporary traditionalist, singing in a deeper-than-Cash baritone. Those are all tendencies that would have been found only in alternative country in the 1990s.

If Lambert tends to laugh off the size of her own contributions to this new expansiveness, that’s by reason of personal experience. “I understand; I do, but I still have to open that door,” she says. “Even now, it’s so freakin’ hard!”

Lambert arrived in Nashville with all the interest in fashioning hit singles that an alternative country act has traditionally mustered. Which is to say, of course, very little at all.

“I wrote without any kind of thought about any kind of single,” she recalls, looking back five, six years. “I was kind of opposed to it, almost, like that ‘Texas singer-songwriter’ referring to a ‘Nashville’ single. You know?

“I grew up in Texas music. That was where I started, and that’s what I did. I’d be playing at one of the Texas music shows in a tent; I’d open up, like at one o’clock in the afternoon for an all-day festival, where people would be chanting, literally, ‘Nashville sucks! Nashville sucks!’ And I was thinking that any one of us would take a record deal in a heartbeat.

“There were guys like Pat Green and Jack Ingram who finally got out there, when the opportunity came,” she continues. “They were open-minded enough not to say, ‘Well, we’re just goin’ to stay in Texas; screw everybody else.’ Why wouldn’t you want to get our kind of music out there? My goal never was to stay in Texas and sing about beer and burritos.”