50 STATES OF FOLK: Chanteys on Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay

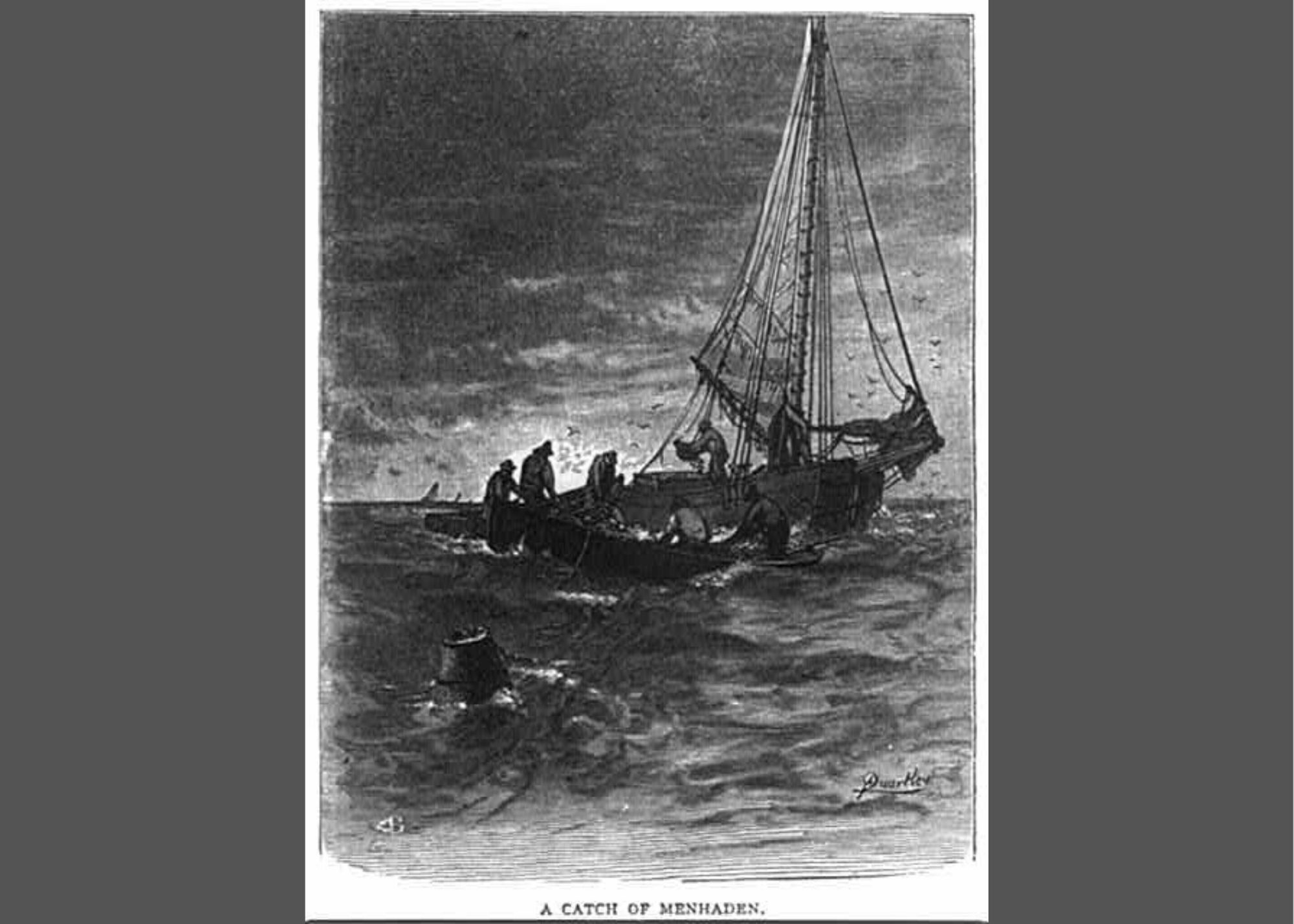

Illustration circa 1884 in The New Long Island / via Library of Congress

For as long as there has been work to do, there have been people singing while they do it. Collaborative tasks, in particular, seem to lend themselves to song. These songs do more than just help pass the time; they often help to coordinate efforts, with the rhythm itself being a tool for the workers. For centuries, the Mbuti of the Congo have incorporated distinct whistles and yodels into their hunting songs, allowing for the hunters to communicate the locations of themselves and their prey throughout the hunt. It is thought that farmers in 15th-century Holland sang an early version of “Yankee Doodle” while collecting their harvests, with the rhythm helping to set their pace and actions as they worked.

But one of the most iconic forms of work song is the chantey (or shanty), a working song meant for the water. Nowadays, the iconic popular imagery of sailors singing chanteys probably looks pretty white — Anglo-Saxon men on whaling ships singing songs about Old Ireland and drinking. But this couldn’t be further from the true evolution of seafaring songs. In fact, almost every hallmark trait of the canonical sea chantey comes from the working songs of Africa, transported to the New World, including coastal Maryland, via the transatlantic slave trade.

A Brief History of Singing on the Water

While the modern form of the “sea chantey” wouldn’t be invented until much later, there have been bored people performing difficult and repetitive tasks on boats for as long as boats have floated on water.

There is a description of a rowing song in the ancient Greek novel Daphnis and Chloe, written sometime between 200-400 AD. Boatmen on the Zaire (Congo) River have long used (and still use today) call-and-response singing patterns to synchronize their work. And as early as the mid-16th century, you can find references to a Celtic maritime work song tradition, with a handful of heaving and hauling chants cataloged in the famous Complaynt of Scotland.

But despite all this history, the work song was truly perfected as an art form by New World Africans. In 1806, a white observer in Martinique marveled that “the negroes have a different air and words for every kind of labor; sometimes they sing, and their motions… keep time to the music.” It was from this branch that the chantey would grow.

Menhaden Fishing on the Chesapeake

Menhaden, sometimes referred to as “the most important fish in the sea,” have almost certainly defined your life experiences in ways that you don’t realize. No one just eats them — they’re oily and pungent and packed with tiny bones — so you can’t pick up a pound at your local supermarket (I know you were curious). And yet they are arguably the most important fish caught along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, exceeding the tonnage of all other species combined. We eat fish that eat menhaden, with 19th-century ichthyologist G. Brown Goode exaggerating only slightly by declaring that people who dine on Atlantic saltwater fish are eating “nothing but menhaden.” They are used as high protein feed for chicken, pigs, and cows throughout the meat industry. They are cooked down to extract their fatty oils for use in paint, linoleum, and dietary supplements.

But back in the 1800s, menhaden had other purposes: most notably oil and fertilizer. So it’s no surprise that there existed a booming industry for menhaden fishing on Chesapeake Bay in Maryland and Virginia, where the waters teemed with enormous schools of this small, homely fish.

Fishing for menhaden requires the use of purse seines — large nets that float at the surface of the sea and hang down deep into the water, ideal for catching an entire school of fish at once. To use the purse seine successfully, it must be cinched shut and hauled aboard by a team of fishermen working in unison.

It was backbreaking work, hauling in thousands of pounds of smelly, slimy fish at once, and the pay was set by the “share” or “lay” system, meaning men would get their salary based on how many fish they were able to bring in. These New World boatmen — mostly African American and Irish men — used a call-and-response pattern and occasionally the beat of a drum to keep the rhythm of the work, very similar in style to work songs heard off the coast of Ghana in the 1790s. Sometimes they sang established songs, usually Christian spirituals like “Roll, Jordan, Roll” and “Drinking Wine, Drinking Wine”. Often, though, the workers came up with the words and rhymes themselves, using them to express the emotions that came from harsh labor (e.g., “Going Back to Weldon”) and the homesickness of being on the water away from home. Eventually, singing in the chanteys came to be an unspoken requirement of the job: Lift your voice with the crew and keep good time, or you wouldn’t be back on the boat.

Changing Tides

Chanteys and other related work songs could be heard all throughout the South wherever freed African Americans found work. Black firemen on steamboats sang at their work, as did the stevedores and fishermen in Southern ports. It was quite common to hear work songs sung from crab-picking houses in North Carolina, among both black and white pickers. This is likely how chanteys began to spread and mix with Irish and Irish-American culture, as more and more Irish immigrants sailed across the Atlantic while fleeing the Great Famine. With all these men working on the same boats and in the same factories, and with everyone expected to sing together to maximize productivity, is it any wonder that Irish immigrants would adopt some of this music into their own expansive folk tradition? Or that some of their ballads and stories would become incorporated into the chantey tradition?

However, the broadly popular perception that chanteys originated in the British Isles, and the subsequent erasure of African Americans from the tradition, wouldn’t become prominent until the British folk music revival of the mid-20th century, as led by the amateur English folklorist A.L. Lloyd. His work would nearly single-handedly standardize the revived chantey tradition, creating “standard” forms of “traditional” songs that, of course, were traditionally improvised. These new, standardized versions, combined with the decades of work by white folklorists that fed into them, helped both to preserve the then-largely extinct chantey-singing tradition and to propagate a cultural myth that chanteys first originated from the British Isles.

Chanteys aren’t sung much anymore, as industrialization eventually eliminated the need to take large crews of men onto the water to haul in a catch, shovel coal into a furnace, or shuck oysters by hand. Moreover, the singing of work songs is now largely associated with slavery and forced labor in the minds of African Americans, leading to a sense of distaste with the tradition. But the improvisational nature of chanteys (along with their bawdy and sometimes rude nature) can still be seen in many styles of African American music to this day — most notably in rap and hip-hop, whose artists often prize themselves on the ability to create innovative rhymes and stinging diss tracks on the fly. As for chanteys themselves? You can probably still find those in your local Irish bar close to closing time — just be sure to let them know where they really came from as you sip a Guinness and sing along.

For a sampling of all-American sea chanteys, give a listen to this month’s 50 States of Folk playlist!