50 STATES OF FOLK: How Illinois Launched a Worldwide Ragtime Craze

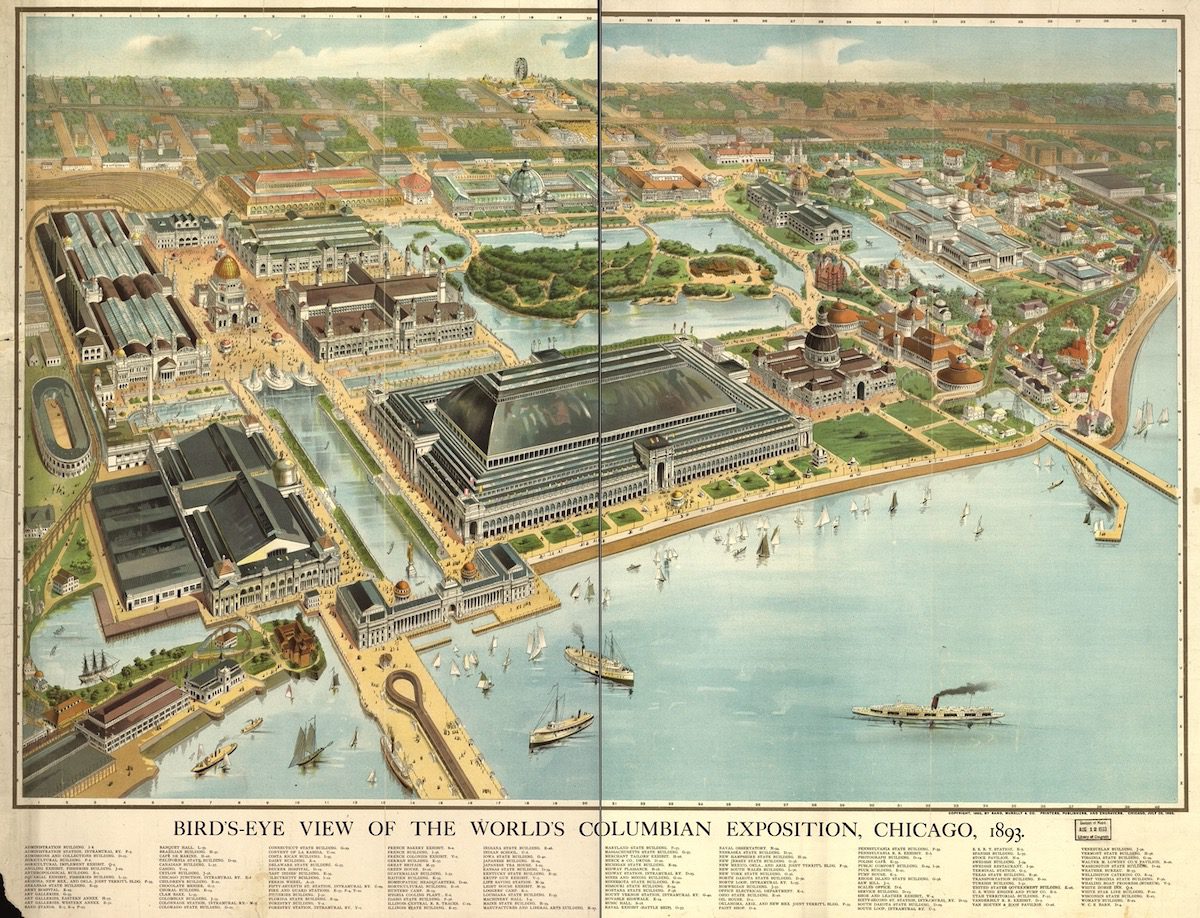

A Rand McNally and Company map showing a bird's-eye view of the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, 1893. (Photo via Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division)

As previously discussed in this column, much of what we consider to be “roots music” these days stemmed directly from the Black experience in America. Spirituals and gospel have their origins in the field churches of enslaved Black Americans. The blues were born in the financial despair of Reconstruction. Old-time and bluegrass wouldn’t exist without the banjo, an all-American instrument descended from similar folk instruments seen in dozens of West African cultures. I could go on and on (and arguably I do by having this column in the first place).

Ragtime, a jaunty and danceable progenitor of jazz, fits right into this same narrative. And while stylistically it is rooted in the sounds of the South, ragtime got its start — and began its rise to worldwide cultural domination — at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

The Black Roots of Ragtime

Much like with the blues, ragtime as a style can be traced back to Reconstruction. At the time, many Black folks were relocating from the rural landscapes that had dominated Black American life to that point and moving into urban centers, abandoning the places that had imprisoned them and their families for generations. Additionally, Black Americans were plagued by racist imagery and violence tying them to the South, as seen in popular art of Black individuals eating watermelons and in wildly popular touring minstrel shows that featured white performers in blackface playing banjos. So, in an attempt to navigate around these stereotypes and claim a new narrative for themselves, many Black musicians transitioned away from the outdoor, porch-jam styles of music that they had pioneered and instead opted to blaze a new trail, playing in nightclubs and dance halls.

In these nightclub shows, the artform of the blues started to arise out of African American spirituals, using musical elements such as call and response and repetition to embrace new themes of love, sex, and poverty.

Similarly, elements of Black banjo music began to be adapted into early ragtime. Banjos and fiddles shifted away from being associated with Blackness, and pianos and horns began to replace them in the American psyche. In these crowded, dark nightclubs and halls, musicians needed instruments that could provide more volume and power than the acoustic string instruments that had dominated Black life in America up until this point.

“Some predecessors of ragtime believe the chords played with the left hand on the piano took over the function of the banjo while the left hand played the melody provided by the fiddle,” said Paul Wells, founder and director emeritus of the Center for Popular Music at Middle Tennessee State University, in a 1998 Chicago Tribune story about the roots of country music. Meanwhile, ragtime took its characteristic syncopation from both the bum-ditty of frailing banjo and from the dance known as the Juba — which later evolved into the 1900s dance sensation known as the cakewalk.

However, despite the efforts to avoid racist stereotypes and dismissal, they still followed wherever Black folks went. This can be seen in contemporaneous records, such as this observation from essayist Lafcadio Hearn from 1881: “Did you ever hear negroes play the piano by ear? … They use the piano exactly like a banjo. It is good banjo-playing but no piano-playing.”

The 1893 Chicago Expo and the Heyday of Ragtime

Ragtime didn’t become a cross-cultural phenomenon — breaking through to both white and Black audiences in America and abroad — just because of its danceable syncopated beats. It became a smash hit, in large part, because it was written down.

For generations, Black American music had been passed down through aural traditions. This is certainly true of European folk music as well. Written music, however, gained prominence and preference among wealthy, urban whites amid decades (if not centuries) of gatekeeping access to Western music instruction, including notation. Having published sheet music of the hottest new pop sensation helped make it accessible to affluent white music enthusiasts and fans, giving them an entry point to learn and play the music themselves. So even though the transcriptions were simplified compared to the often highly improvised and ornamented live performances by Black musicians, these written copies helped to propagate ragtime into new circles, lighting a fire that later became a craze for “Negro music.”

This ragtime fever can be traced back to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. More commonly known as the world’s fair, the event drew more than 27 million people, making it the grandest and best attended American exposition to date. In attendance were ragtime pioneers such as Ben Harney, Scott Joplin, Jesse Pickett, and Johnny Seamore (sometimes referred to as the “father of ragtime” among his musical contemporaries). While they and the other Black musicians present likely weren’t featured within the fairgrounds where the expo was held, they were performing all around town and the crowds were still exposed to this new, jubilant sound as they visited Chicago. When ragtime began to spread across the US in earnest as a new genre, the Chicago expo was still being cited as its place of origin.

But that would take a few years. The first piano rag that was written down and published was “Mississippi Rag” by William Henry Krell. As a white composer based in Chicago, Krell had gotten his start composing waltzes and ballads. In fact, he is credited with publishing one of the first transcriptions of a cakewalk, titled “The Cake Walk Patrol.” But as a touring musician in the 1890s, he spent significant time in the South, exposing him to the work and style of Black musicians who were advancing beyond the cakewalk and into early ragtime. Upon his return to Chicago, Krell’s publisher was holding a music writing contest, and Krell submitted “Mississippi Rag” — a simplified transcription of a number he had composed for his band to play on their tour. He won the contest, and “Mississippi Rag” was published on Jan. 27, 1897, marking the first time that sheet music with the word “rag” in the title was circulated.

Despite the name, “Mississippi Rag” wasn’t actually a genuine ragtime number — it was simply another cakewalk in the same style as his earlier composition, “The Cake Walk Patrol.” But in using the name, he landed himself a place in history. And with the song’s success came a deluge of rag pieces that would ultimately become a two decades-long sensation.

Contemporary Impact

It’s important to remember that, despite earning himself the distinction of being the first person to publish a written piano rag, Krell was not responsible for the popularity of ragtime. That credit belongs to the Black musicians and composers that created this new genre wholecloth out of their own varied musical traditions, particularly those living in the South. It was those musicians that inspired Krell in the first place, and it was those musicians that were systemically barred from access to the same kinds of opportunities to submit to competitions and get their work published that allowed Krell to get there first.

Nonetheless, the work of countless musicians and fans of all backgrounds kept the momentum going. Shortly after the publication of “Mississippi Rag,” Tom Turpin became the first Black composer to publish ragtime sheet music with his “Harlem Rag” (written in St. Louis, obviously). Two years later, Scott Joplin would publish what is largely considered to be the seminal piece of the genre, “Maple Leaf Rag.”

Although the ragtime fad itself faded by the 1920s, its impact did not. As the craze began to wind down, new evolutions such as stride and novelty piano cropped up, with ragtime and its canon at the heart of new compositions from musicians like Fats Waller. In the 1940s, there was a renewed interest in traditional or “Dixieland” jazz that resurfaced many lesser known rags, inserting them into the repertoires of swing bands featuring performers like Lu Watters and Pee Wee Hunt. Later, ragtime experienced a popular and academic revival in the ’60s and ’70s as record labels set to work republishing and rerecording seminal works from ragtime composers like Joplin and Eubie Blake.

However, the most famous example of modern ragtime that you’re likely familiar with is one that may come as a surprise: the 1967 smash hit by The Beatles, “When I’m 64.” Interestingly, and almost certainly unintentionally, this bouncy and lighthearted number asking if the listener will still love the singer when he grows “old” was released just about 64 years after ragtime hit its heyday as the pop music of America. In a way, the song answers its own question. Yes, Paul McCartney, I believe we do still love a good rag — even after all these years.