50 STATES OF FOLK: How the Banjo Put Down Roots in North Carolina

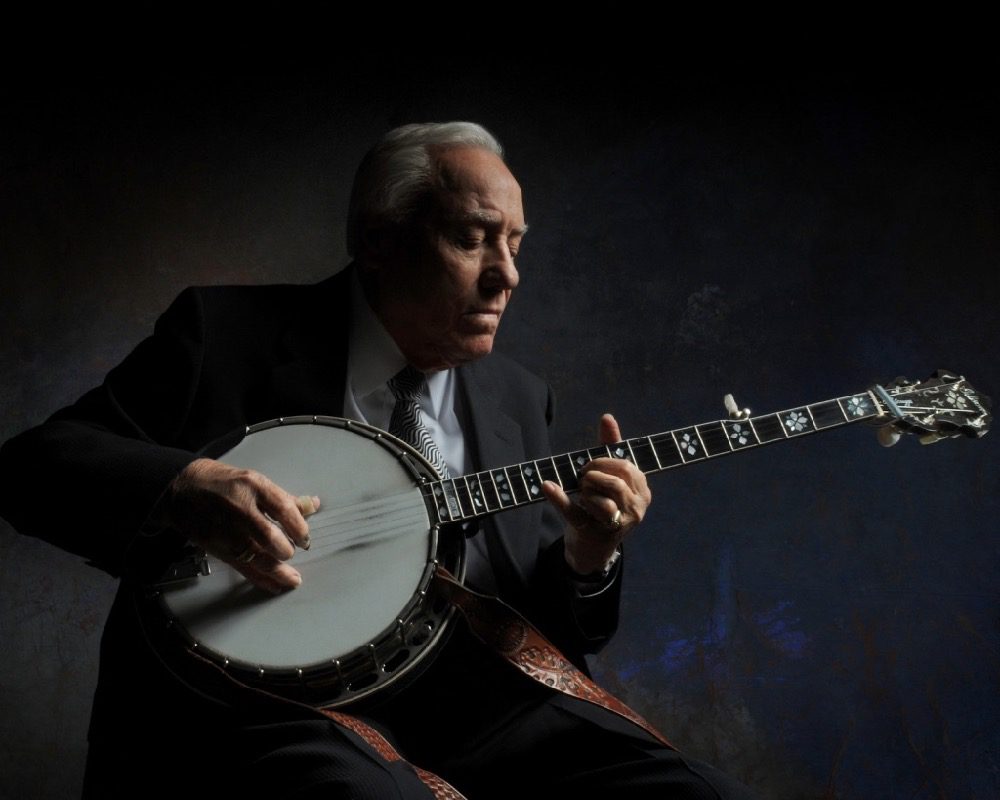

Earl Scruggs (photo by Jim McGuire)

We’re all familiar with the sounds of the banjo, popularized in the American imagination by media highlights like the dead-eyed banjo picker in Deliverance and the band on Hee Haw. But more than anything, you would recognize the iconic, rollicking sounds of The Beverly Hillbillies theme song, played by arguably the most famous bluegrass duo of all time, Lester Flatt and North Carolina’s own Earl Scruggs.

But if your idea of the banjo is simply the rapid-fire brash and brassy notes heard in Southern bluegrass bands, you’re missing a big part of the story. Before the banjo became a feature in classist stereotypes against poor white Southerners, it was a feature in racist blackface minstrel performances. And before that? It was played on the shores of western Africa before being stolen and sold by white America.

Coming to America

Long before America was founded, people in West Africa were playing hide-covered string instruments similar to the modern-day American banjo. There’s the ngoni, featuring anywhere between 3 and 9 strings, which was usually reserved for ceremonial purposes among the people living in what is now Gambia. There’s the xalam, thought to have originated in Mali, which featured between 1 and 5 strings tuned to a chord. There’s the akonting, a folk instrument played by the Jola people, featuring two melody strings and one short “drone” string that would be familiar to any modern-day banjo player.

While the akonting is widely viewed by academics as the most likely direct ancestor, there are dozens of instruments in West Africa that could be progenitors to the modern American banjo. It is quite likely that there is not just one African instrument that can claim sole parentage, but rather that the evolutionary tree of the banjo leads to many, if not all, of these similar ancestors.

But one thing is for certain: They all came to America via the stolen people of Africa, who traveled across the ocean as part of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, bringing with them the memory of how to construct these instruments. When they arrived — first in the West Indies, and later in the American mainland — they were able to build them from the materials they found on hand: gourds, goat and cat hides, lumber, and strings made from the guts of livestock.

By the late 18th century, the banjar (as it was then known) had become widely popular among the slave populations of mainland America, with Thomas Jefferson himself having once remarked of his slaves: “the instrument proper to them is the Banjar, which they brought hither from Africa.” Slave masters, in recognition of the musical talents of their slaves, often forced them into providing entertainment — such music and calling for dances — which showcased the beauty of the banjo to white and black audiences alike. It wasn’t long before white people began trying to learn how to play the instrument themselves, often seeking instruction from their slaves and other free blacks.

And how did white folks thank their instructors for these newfound musical skills, gained through cultural interchange with a vulnerable and abused population?

With blackface minstrel performances, of course.

Frailing Up

Banjo players at the time typically played in a frailing style, a brushy rhythmic playing style where the picking hand is held in a semi-rigid “claw”-like shape and the melodic strings are plucked in a downward-picking motion using the back of the player’s fingernail, all accompanied by the thumb being used to pick the drone string on the off beat. This kind of downpicking style has no known origins in European music, but as previously noted, has deep roots in the musical heritage of western Africa. And it was this style of playing, iconic to black Americans in the late 18th and early 19th century, that would come to be emulated and mocked in the minstrel tradition.

Joel Sweeney of Appomattox, Virginia — who was taught how to play the banjo by the enslaved workers on his father’s farm — is probably the person who can be best credited for popularizing the banjo as an instrument. He did so by bringing it to the fore in racist blackface minstrel performances, featuring frailing banjo performances accompanied by comedic routines lampooning the very people from whom Sweeney and his brothers — known together as the Virginia Minstrels — learned the music.

Through the Sweeneys personally, and minstrel performers more broadly, the modern-day American banjo became standardized, featuring a drum-shaped “pot” (rather than a gourd) and four strings tuned to a chord plus a fifth, shorter high-pitched drone string, or chanterelle. Even later on, as the vaudeville-style of banjo music became more popular (and people shifted toward wanting to play the louder tenor and plectrum banjos), the minstrel five-string banjo had staying power, particularly in North Carolina and throughout Appalachia. This localized presence would continue over the decades, even as tenor banjos faded in popularity following the invention of the electric guitar in the 1930s.

Poole & Scruggs: The Invention of the Carolina Three-Finger Banjo Style

In the 1870s, the first “finger-picked” styles of banjo playing began to emerge. First mentioned in Frank B. Converse’s 1865 instruction book Method of the Banjo With or Without a Master, this style was quickly adapted into ragtime by musicians like Fred Van Eps. Van Eps appeared in some of the earliest recording sessions, where the banjo was a popular instrument due to its sharp punchy sound.

Born in 1892, North Carolina native Charlie Poole grew up hearing the banjo and listening to these early records. After a childhood baseball accident permanently injured his hand, he could no longer play in the more popular clawhammer style and had to switch to the lesser-known three-finger style that he’d heard in these “classical” and early jazz banjo recordings. He would go on to form a band called the North Carolina Ramblers that toured around the Piedmont and beyond playing their own unique style of old-time music. They recorded several popular albums with Columbia Records — most notably their breakout recording of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” in 1925 — that laid the groundwork for the Carolina three-finger picking style to become a full-on fad.

However, after Poole’s untimely death in 1931, the mantle was laid down. Some other players kept the tradition alive at a smaller scale, including Snuffy Jenkins and Don Reno, but it didn’t become a global sensation until Earl Scruggs arrived on the scene.

Scruggs grew up in a family that loved music, in an area of North Carolina known for its banjo enthusiasm. He picked up his first banjo at age four, and first learned to play using a two-finger picking style. Famously, he would not learn how to play in his now iconic three-finger picking style until he was 10 years old, when he got into an argument with his brother and went to his room to practice his banjo and blow off some steam. While stewing in his anger, he realized that he was accidentally playing in the three-finger style that had been giving him trouble for so long.

He would go on to smooth out his playing, adding a syncopated rhythm and emphasizing melodic lines across his arpeggiated rolls, inventing a style that was intrinsically North Carolinian while also being uniquely his. At age 21, he would join Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys, forever changing the way that the world heard the banjo and helping to create what is now known as the iconic, hard-driving bluegrass sound.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Hear more of that history of the banjo at this month’s 50 States of Folk playlist:

Special thanks to Jake Blount, who assisted with research and fact-checking into the early history of the banjo and its West African ancestors.