The Irish African and the African Irishman

Abstract:

It is commonly said that black face minstrelsy is the first popular-professional musical business in America. I am only at the beginning of grasping its full impact on later music evolution as the blues. But before starting this exercise it is essential to understand that black face minstrelsy was not a one dimensional phenomenon. There are quite some differentiations to bring to the stereotype image of the white actors, with black cork painted faces playing the banjo, fiddle, bones and tambourine. In this article I present a first flavor of those differentiations.

___________________________________________________________________

The blues are in the first place a vocal art of which the antecedents go back to field hollers, ring shouts, corn shucking songs and spirituals. The instrument accompanies the singing in a call-and-response structure wherein it functions as the partner in a dialog with the voice that plays the leading role. It is thus no surprise that more attention is being paid to the vocal pedigree of the blues than to the precursor of the instrumental component of the blues. Yet, the instrumental roots are not less important, on the contrary, and are at least as fascinating to study as the way that the different form of slave songs and the spirituals have left their marks on the blues.

The stereotype of the wandering blues man with his guitar misleads us in our exploration of the the instrumental forefather(s) of the blues. There is discussion on how the guitar has made its entry on the blues scene at the end of the 19th century. Some contend that the instrument might have been introduced in the Deep South through Spanish, Mexican or Caribbean influences. Others remind us that in West Africa the didley bow, a one string instrument, was very common and that there are enough documentation of blues artists who started their career attaching a string to the wall to play their first tunes. More blues men however have learned the trade by playing their first riffs and chords on the banjo. What the didley bow and the banjo have in common is that they can be easily constructed from readily available material found anywhere, unlike the guitar which requires some craftsmanship to put together. The banjo was by far the first and most popular (folk) instrument that was introduced in America.

The dominant theory is that the banjo as it developed in America had its ancestor in the African ‘banjar’, an instrument with a skin stretched over a gourd or hoop. It has been brought over physically on the boats that transported the first slaves directly from Africa or indirectly from the Caribbean, or it has been manufactured after the slaves’ arrival following their memory. Its further influence and spread through the American culture, black and white, is subject to more controversy. Some scholars have found material to support their thesis that the banjo playing at the end of the 19th century has been directly impacted by the African American traditions and techniques. They contend for instance that the white mountaineers in the Appalachia have learnt their skills from black musicians already at a very early stage. Others dispute the material and put forth observations that are more congruent with the supposition that the popularity of the banjo and its dissemination in the American culture has been driven by the success and the proliferation of the minstrelsy companies. I am not in position to judge the validity of either position, but I believe that there is no simple model that can cover the complex reality of the black and white cultural exchange. The paucity of the material that is at hand and that has been researched so far makes it nevertheless plausible that there has been a constant coupling in both directions between white and black culture making it hard to distinguish at the end of the day what has been cause and what has been effect. This is especially the case where geographically and socially close contact between the African and European immigrants was possible, as it was in America with its relatively smaller plantations in contrast to for instance the West Indies.

Whatever way the ‘banjar’ influenced the banjo playing in the late 19th and early 20th century in blues and other genres, the historic role of the minstrelsy as the first major popular music business can hardly be underestimated. Ken Emerson contends that minstrelsy swept the world in the 1830s and 1840s much in the same way that rock and roll did more than a hundred years later, or in the same way that Elvis Presley electrified the world. From its early popularity at the end of the 1820′s until the end of the 19th century, when it gradually became a shadow of itself making place for ragtime, vaudeville and blues, it was indeed a key institution that offered popular entertainment in America, mainly but not exclusively in the northern industrial cities. It cannot be a coincidence that minstrelsy lost its popularity and that other music genres as blues emerged precisely at the moment that it could no longer be ignored that the Reconstruction efforts had failed, that it became manifest for the African American population that the industrialization had once again degraded the African American to a second grade citizen and that Jim Crow made itself felt more and more. The legacy of the minstrelsy and the marks that it has left on the later music popular music business, of which the blues is just one, is still to be further explored in detail.

Its very complexity and susceptibility to different interpretations make such an exploration a difficult task. In what follows, I can only present a first flavor of the multi layered composition of minstrelsy as the first popular-professional American entertainment. I will do this by showing that there are some extra hues present in the general popular painting of this show business, in other words – to stay in the color scheme – that there are quite some grey shades between black and white.

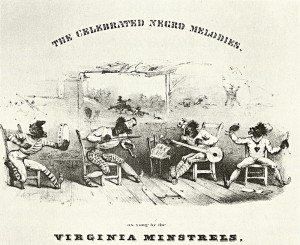

In general terms, minstrelsy is defined as an organized entertainment form consisting of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music, performed by white people in black face. In minstrel shows, aimed in the first place at the labor classes of the population, the African American was showcased as a musical and joyous, though ignorant, lazy, buffoonish and superstitious person, a loud-mouthed plantation mammy, an overdressed male dandy, a sexually promiscuous light-skinned woman, or a compliant Uncle Tom. It was in its essence a hymn of the happy plantation life. The Virginia Minstrels – lead by the famous Dan Emmett who introduced the show as a fully fledged evening entertainment in 1843 – represent the typical and stereotyped minstrel show company: white musicians, black faced, white managed and using as instruments the banjo, the fiddle, bones and a tambourine.

However, there is more to it than this stereotype.

Already before the 1830s there existed black face entertainment: by the late 17th century, black face characters appeared on the American stage, usually as “servant” types whose roles offered some element of comic relief. What happened at the end of the twenties was that black face minstrelsy kicked off as a formal and well-organized entertainment industry molded by a small number of people who then started touring nation wide and even internationally. The entertainment transcended the pure local context.

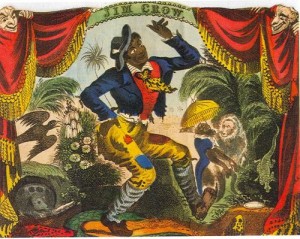

The years 1828 or 1829 are usually quoted as the birth period of the minstrelsy when Thomas Dartmouth Rice – “Daddy” Rice – a minor, white character actor from New York City – was in Louisville, Kentucky. The story goes that Thomas Rice had the idea of dressing in shabby clothes – a tattered coat and too-short pants, oversized shoes, and a felt hat – from an African American whom he met in the streets of Louisville and who inspired him to develop a song-and-dance routine in which he impersonated an old, crippled black slave, dubbed Jim Crow. It is worthwhile (and ironic) to note in the perspective of the role of the banjo and the minstrelsy that whilst the minstrelsy was in its first decade limited to song and dance, without banjo or fiddle, there are indications that the acts that might have inspired Rice were precisely a combination of dance and banjo. The name that pops up here is that of John “Picayune” Butler, a black French singer and banjo player who lived in New Orleans. He is said to have come to New Orleans from the French West Indies in the 1820s when he started touring the Mississippi Valley performing music and clown acts. He built up a reputation as one of the very few nationally known black entertainers from his period, having a fame by the 1850s that reached as far north as Cincinnati in Ohio. In 1857, John Butler even participated in the very first banjo contest in America held at New York City’s Chinese Hall. However, between his magnificent playing and the first place at the contest stood a few drinks too many. Notwithstanding, John Butler is one of the first documented black entertainers who have had an impact on American popular music and who influenced black face entertainers most directly. Conway (1995) quotes that a circus performer named George Nichols claimed to have learned the famous “Jump Jim Crow”, the hall mark song of black face minstrelsy, precisely from this John Butler.

The stereotype image of minstrelsy as a group playing the banjo and later the fiddle, bones and tambourine needs thus a first nuance to the extent that though it was probably inspired on black folk music and banjo, the latter instrument and the other ones were added only in a later stage. It is said that banjo was only added around 1840. Minstrelsy was in the first place in its infant years a matter of song and dance. Allow me an ironic step aside at this point in quoting the dance as a major act: the cakewalk dance, which would be popularized by the minstrelsy in later years, was originally a slave dance which mocked the plantation owner…a dance which thus became popular to a white audience which was originally the subject of the skit by the same people that were being mocked by the dance in the minstrelsy context…

A second shading to bring in the stereotype is that the African American population was not the only social group that formed a theme of the minstrel stage act. Germans for instance were depicted as robust and burly, speaking some kind of ‘Dutch’ dialects, indulging an immense appetite for sauerkraut, sausage, cheese, pretzels and beer (Bean et al.). The men frequented large saloons, drank way too much and got themselves constantly in debts. German women also had the bad habit of eating too much, resulting in a ‘but like a shack horse’. But all in all, Germans were at the same time painted as hard working, proper and practical people, contrary to the Irish who were even more ridiculed in the minstrelsy than the Germans. By mid 19th century, the prejudices and discrimination against the Irish were significant as they were a fast growing group that as a cheap labor force was seen as bringing down the wages. And, they were Catholic: next to the fact that they were depicted as ignorant, fighting and heavy drinking fools not knowing how to do anything right, they were seen as agents sent by the Vatican to attack from within the American Democratic experiment. Only when the Irish themselves became in later years more and more involved in the performance and organization of minstrel shows, their image became more and more favorable and softer. They became to enjoy a more favorable treatment on the minstrelsy stage than the Germans.

Minstrelsy was furthermore not an exclusively white business. Blacks entered the minstrelsy in large numbers after the Civil War as performers and even as managers. The white managers of the minstrelsy before the War became accompanied afterwards by black managers who started to organize their own companies (Hill and Hatch). In fact, the black face theater seemed the most obvious venue for the African American to participate in the lucrative music business. As an entry ticket to the business, the African American had however to paint his face black, to use a “darky” dialect and to present the same stereotypes as those acted by the white black faced minstrels. He had to do what the audience expected from him.

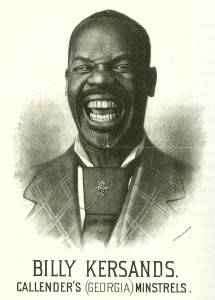

One of the most famous and then popular black comedians and dancers was without any doubt Billy Kersands. Next to comedy and dancing he excelled equally in acrobatics, singing and instrument playing. His trademark was his large mouth which he could twist exuberantly and comically or fill with objects as billiard balls or saucers. As a contemporary journalist noted: “The slightest curl of his lip or opening of that yawning chasm termed his mouth was of itself sufficient to convulse the audience.” This audience was by the way both black and white. For the white, the 200 pound weighing man with the big mouth fitted precisely the racist, white-created stereotype of the black. Moreover, Kersands also performed songs that reinforced the racist stereotypes. For the black audience that appraised him quite largely, he was appealing because he mixed African American folklore in his show in a way that was not directly obvious to the white. Kersands may also have introduced the Virginia dance (Essence of Old Virginia), a dance that later developed into the ‘soft shoe’, a form of tap only done with soft soled shoes without metal taps attached. In this dance he moved forward without appearing to move his feet at all, by manipulating his toes and heels rapidly, so that his body propelled without changing the position of his legs. Does this dance look familiar to you? Yes? No wonder, the “Virginia Essence” was the precursor to and the basis upon which Michael Jackson based his famous Moonwalk in 1983. (I am tempted here to observe that Michael Jackson has been said to have ‘whitened’ his face…was this then ‘white faced’ minstrelsy? ).

Kersands, at one point in time in the 1880′s, became the manager of his own troupe of minstrels, which became well known for its marching band music, that became very popular by the end of the century. As a manager he took over from Charles Hicks, who tried to resist somewhat the minstrelsy’s dominant “darkydom” and introduced non racial ballads such as “See that my Grave’s Kept Green”. He stressed, as dit the other groups, the slave origins of his show – after all : the slave label was viewed as a commercially vital hall mark – but tried to avoid nevertheless too many songs about the longing for the good old plantation days.

According to himself, Hicks was born as a slave around 1840 and may have been previously employed by a white minstrelsy company. He earned the reputation as one of the best press agents and managers in the business, a born business man (Hill and Hatch). Still according his own saying, he started the first company of genuine Negro minstrels that had been successful in touring America: “The Original Georgia Minstrels”, where he acted as manager, owner, balladeer and comedian.

His success didn’t make him very popular amongst the white owners of the other minstrel groups who continued to dominate the market. Without doubt, this competition and even hostility must have contributed to his decision to tour also abroad. In 1870 he was the first one to organize a tour of minstrels in Germany. In 1877 he started a popular three year tour in Australia and Tasmania, where he surfed on the curiosity of the audience to see exotic acts. Upon his come back to America, the heydays of minstrelsy were over and his successes were few. He died in 1902 in Java.

Charles Hicks was not the only black manager in the minstrelsy business. Between 1866 and 1897, another entrepreneur, Lew Johnson managed successively four minstrel companies (Peterson). In 1898 he was even active with the predominantly white (18 of the 20 actors where white) ‘Tom Show’ troupe, which toured the west with its production of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. He spent his last days as manager and lessee of the opera house in Grand Forks, British Columbia.

Contrary to Hicks, Johnson toured mainly the rugged terrain, small towns in the Midwest, mining camps in the West and in Canada where he was in less competition with the other troupes. According to Booker T. Washington it was during a tour on the West Coast that Johnson hired a young, then unknown performer: Bert Williams, who would a few decades later become one of the first important black super stars (Obrecht, 2011). Competition remained tough however. Hill and Hatch cite a total of 149 visits of minstrel groups to Seattle between 1864 and 1911 of which one third was from colored troupes. But Lew Johnson had the reputation of being one of the best. He was moreover one of the first managers to carry a brass band on a road tour. Hill and Hatch (p. 117): “to attract an audience, a company would disembark from the train in their uniforms, playing as they marched to the theater, a practice called “dragging the town”. Let us note in the margin that this organized trip from the station to the theater had the supplementary advantage of protecting the black group members from possible hostility from the white townsmen.

A final differentiation that I feel to be relevant to bring to the general stereotype of the minstrelsy is that whilst it is true that before 1865 it was largely a white-owned and white-performed business, there were nevertheless even before the Civil War a few black-controlled, black minstrelsy groups. Robert Toll in his ‘Blacking up : The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America (1977)’ quotes six such groups, who had however a very short lived career. Jack Shalom (1994) adds a seventh one, which seemed important enough that a reporter from the New York entertainment journal “Clipper” found it worthwhile to dedicate a complete, detailed article to a performance of the group in 1863 in the Franklin Hall in Philadelphia. It is curious to note that as far as I could trace no other documentation than the quotation from the ‘Clipper’ seem to exist. Yet, this company: “The Ira Aldridge Troupe”, which was probably a professional group, doubtlessly occupies a unique place in the history of minstrelsy, and this for several reasons.

Ira Aldridge was born in New York on 24th July of 1807. His father was a church minister, who sent him to the African Free School where he developed a love of the theater. However, he quickly realized that a career as an actor in America was not to be taken for granted: the young Aldridge left for England. His start in the theater in 1825 was not very successful. A reviewer of “The Times” complained that Aldridge could not pronounce English properly “owing to the shape of his lips”. The actor did not give up and over the next few years he appeared in plays in a number of towns in England and Ireland. His odds turned for the better after his performance in Othello in Scarborough where he was described as “an actor of genius”. He also staged in several white roles as Shylock, Macbeth and Richard III. However, he became the target of racist attacks as a result of which London theaters refused to employ him. He remained however in great demand in the provincial theater and one newspaper described his performance as Othello as being so good that it could only “be equaled by very few actors of the present day.” Because of his boycott by London theater he left England and appeared on the stage in a number of continental towns such as Brussels, Cologne, Basle, Leipzig, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, St. Petersburg and Moscow. It was a lucrative move. In Russia he became one of the highest paid actors in the world. One Russian critic stated that the evenings on which he saw Aldridge’s Othello, Lear, Shylock and Macbeth “were undoubtedly the best that I have ever spent in the theater”.

Despite his voluntary exile from America, his name remained highly praised among the abolitionists, and it is said that he spent half of his earnings to the financing of the struggle of the blacks for freedom. Having this in mind, it is not hard to understand why the minstrelsy group that borrowed his name, had a repertory that stood far from the classical minstrelsy song list that lauded the plantation life. And what is more: they didn’t put on any black face. But what made them truly unique is that several of their acts were no less and no more than subversive in their contemporary political context. One of their songs, unlike many of the then coded slave songs, spoke clearly about the longing of the enslaved African Americans in the south to meet in freedom their free brothers and sisters in the North. Another of their acts was a farce called “The Irishman and the Stranger” where one of the troupe’s members played an Irishman and another one playing the stranger. According to the New York reporter this act was a “truly laughable affair, the Irish ‘naguar’ mixing up a strong Irish accent with a sweet nigger accent. Indeed, just try to depict the scene: African Americans, without any black face, impersonating an Irishman and a stranger. The role reversal couldn’t be bigger since – as I quoted above – Irishmen themselves had come to dominate more and more the minstrelsy impersonating the ‘darky’ Southern slave. The complex racial play, according to the New York reporter, became even more pronounced when the company played the act of a ‘Red man’ (American native) who captured a white Duke, the latter also played by an African American member of the troupe, “who didn’t even bother to whiten his face”.

Note that the audience in the Philadelphia Franklin Hall was not completely black. The Clipper journalist reports that the front row was filled with whites who seemed to react quite differently on the different acts. According to his words, “they laughed in the right places and applauded at the proper time”, unlike the blacks who “behaved very bad, making all sorts of fun of the performers, and openly criticizing everything that was done”.

What the example of the Ira Aldridge company teaches us about minstrelsy is that its success cannot be fully understood without trying to place oneself in the mind of the audience who interpreted the acts in a very particular racial context. The uniqueness of the Ira Aldridge group comes from the fact that it tried to “pirate the piracy” (Shalom): “The history of minstrelsy is also the history of the piracy and the distortion of black culture by whites. The Ira Aldridge Troupe turned minstrelsy to its own ends, with the collaboration of its partial white audience”.

The Clipper reporter concludes his article with a most positive recommendation that the contemporary white minstrelsy groups should see the Ira Aldridge group which could learn them quite a lot. And the white minstrels they learned their lesson well: black face minstrelsy had an extremely prosperous career for almost half of a century. Minstrelsy actors had performed during their heydays in the White House where they entertained such presidents as James K. Polk, Millard Fillmore, Zachari Taylor, and Franklin Pierce. At the end of the century, it had however degenerated into a more amateurish variety show and activity, with – as Marc Twain put it – “a Negro act or two thrown in incidentally”. But its impact was not yet erased: minstrelsy continued in America on radio and on early television. The radio show Amos’ n Andy, performed by the white actors Gosden and Correl, started in 1928. It became a huge success, even amongst the African Americans. Also, many a blues artist had started his career in the minstrel shows, which had lent quite a few of their songs from the minstrel stock, making the black face performer a ubiquitous presence on the medicine stage (Karl Hagstrom Miller). Gus Cannon remembers when he started off his career and had to play the black face fool: “Had all that cork on our face…made us look even blacker…shit…, painted our mouths white…made ‘em look big..I had to have a shot of liquor before the show. If I didn’t it seemed like I couldn’t be funny in front of all them people. When I had one it seemed like them people was one and I would throw up the banjo in the air and really put on a show”. By then, minstrelsy had traveled a long road already…..

____________________________________________

Sources :

_____________________________________________

– http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/foster/sfeature/sf_minstrelsy_1.html

- http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ug03/lucas/cake.html

– Inside the minstrel mask: readings in nineteenth-century blackface minstrelsy, by Annemarie Bean, James Vernon Hatch, Brooks McNamara, 1996

– Black minstrelsy A history of African American theatre, by Errol Hill, James Vernon Hatch, 2003

–http://www.christmas-in-virginia.com/virginia-christmas-dance/

– The African American theatre directory, 1816-1960 by Bernard L. Peterson, 1997

– http://jasobrecht.com/bert-williams-star-ziegfeld-follies/

– Jack Shalom, The Ira Aldridge Troupe : early Black minstrelsy in Philadelphia, 1994 (African-American Review)

– http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/SLAaldridge.htm

– Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sound, 2010