Review of Nick Tosches: Jerry Lee’s Dionysian HELLFIRE and the Raunchy History of COUNTRY

BOOK REVIEWS: Tosches, Nick. Hellfire. New York: Grove, 1982. and Tosches’s Country: The Twisted Roots of Rock ‘n’ Roll. New York: Da Capo, 1984.

If you are interested in the history of American music–country, blues, hillbilly ballads, minstrelsy, jazz, rock and roll–and how they all come together in the hidden back alleys of American history, you should take note of the name Nick Tosches. His Jerry Lee Lewis biography, Hellfire, is by far one of the most beautiful, strange, and disturbing accounts I’ve read about an American artist. Tosches does his homework, extensively researching Jerry Lee Lewis’s ancestral history, the music he was exposed to, his sleepless nights of guilt for playing the devils music, and uncontrollable Dionysian energy that he unleashed only a few years after Sam Phillips found Elvis Presley.

Ben Saunders, a renaissance lit/comic book/rock ‘n’ roll scholar who recommended the book, told me it read like Flannery O’Connor’s fiction. I couldn’t agree more. In one of O’Connor’s essays that I can’t remember the name of, she talks about how even unbelievers in the South are haunted by the ghost of Christ. This biography bears this out in ways which I don’t think even O’Connor could do in her fiction. (That’s not a dig at O’Connor. I love her writing, but I am trying to communicate the enthusiasm I have for Nick Tosches as a writer). Tosches paints Lewis as an artist constantly at tension between his strong religious roots and innate hunger for wildness and sexuality that comes out every time he takes the stage, kicks over the piano bench, starts howling, yodeling, singing dirty songs, (Tosches notes that Lewis was certain that he was going to hell for “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” and its many sexually suggestive successors in the Lewis catalog), and in moments of unparalleled showmanship–drenching the piano with gasoline from a coke can and lighting the whole piano on fire while he’s playing.

There are several anecdotes that stick with me from Tosches book, things Lewis did which make his marriage to 13-year-old cousin, Myra Gale, seem almost commonplace. The book opens with Lewis in 1976, driving to the gate of Graceland, drunk and who knows what else, armed with a .38 derringer, yelling, “I want to see Elvis…You can just tell him the Killer’s here.” (The Killer was Lewis’s nickname from childhood that has lasted throughout his career).Inebriated to the point he can hardly open his eyes, Lewis proceeds to yell at the guard, “Git on that damn house phone and call him! Who the hell does he think he is? Doesn’t want to be disturbed! He ain’t no damn better than anybody else.” When arrested, the cop found the gun to be loaded, and when the officer cuffed him, Lewis replied, “I’ll have your fuckin’ job, boy” (2-3). Wow. You don’t hear stories like that often, and all that happens on the first three pages of the book.

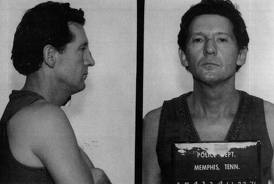

|

| Mugshots of Lewis after typically nefarious behavior |

This is merely one example among several wild instances that Tosches documents. Tosches shows Jerry Lee Lewis to be a true American wild man of Old Testament proportions. For instance, when Lewis returns home from touring and his second wife has had a child, Lewis swears the boy isn’t his, sends him off to the sister-in-law’s house, and curses the child, claiming that the bastard child’s descendants won’t see the kingdom of heaven even until the seventh generation. At one point, when things are reeling far more out of control than the usual unhealthy amount of drugs and alcohol, Lewis shoots his bass player in the chest. He claimed that he didn’t know the gun was loaded.

These anecdotes offer just a sampling of the way that Tosches, who from what I understand is quite a wild man himself while maintaining an personal identification of himself as a Christian, is able to bring to life a career and a body of work that has been largely overlooked because of Lewis’s disastrous personal life. Tosches virtuosity lies in bringing Lewis to life for us, showing that his personal history doesn’t detract from his music (as it has for the past 50 years), but rather, these painful contradicting personalities brought to life in Hellfire make Lewis’s work that much more vivid and interesting.

Nick Tosches has written many biographies on characters as diverse as Dean Martin and the minstrel performer Emmett Miller. He also writes various forms of non-fiction, novels and poetry. His poetry readings are supposed to be “legendary,” as described in his books’ information about the author.

I just finished one of the books he wrote on the country music, Country: The Twisted Roots of Rock ‘n’ Roll(originally publish in 1977 and revised in 1985). If you are at all interested in American music, I can’t recommend this book highly enough. Tosches researches recordings, performance, and variations of songs more thoroughly than I have ever seen in a popular history book. He effectively debunks the myth that country music has always been about family values, working hard, and making an honest living, by bringing you into the sordid world that birthed American music. He spends a great deal of time talking about country music’s origins in the minstrel tradition, the setting where yodeling was first implemented into American song. For instance, he documents how revered country music legend Jimmie Rodgers, the oft-called “father of country music” and original blue yodeler, as well as country-swing legend and Grand Ol’ Opry regular Bob Wills both began their careers wearing blackface in minstrel shows.

Tosches also traces genealogies of traditional country songs. He can trace certain songs back as variations of broadsides ballads sold in the streets of England, the equivalent to our pop music, back to variations of medieval ballads and even back to ancient mythology on one occasion. His writing is thoroughly researched, never dry, and stylistically unpredictable–in a good way. But throughout both books, there is a gritty tone, descended undoubtedly from Bukowski and Raymond Chandler, uncommon in works of non-fiction. It seems like your hearing these stories from a slightly inebriated Tom Waits who has his ear to the ground trying to understand America in all its expressive forms over countless glasses of whiskey and cigarettes. He gives you the impression that he’s been around the block, seen a lot things, had a lot of good thoughts, but the last thing in the world he want is to write like a stuffy academic. This is where the unique quality of his writing comes through. Its informative without being pedantic and historical without being sanitized. His writing forces you to feel songs viscerally that you may have heard a thousand times without feeling anything. For me, Tosches also opens up worlds of American music that I hadn’t even encountered yet. I look forward to reading more of his fiction and poetry as well. Considering the power of his creative voice in the non-fiction realm, I can only imagine what he is capable of in these even less restricted forms. In short, in Tosches I find an eye and an ear that brings to light both the most gritty and the most sublime moments of the American aesthetic–and often Tosches shows us how thin the line is that separates the two.

- Marlon Brando’s Jazz-Culture Cool in an Era Before Elvis

- Keith Richards’s Coda: Review of His Autobiography, LIFE

- Woody Allen, Leon Redbone, and the Tricky Business of Cutting a Joke

- Elvis, Bill Monroe, and that Ol’ Blue Moon of Kentucky

- James Booker and the the St. James Infirmary

- Nic Cage is a Really Good Bad Lieutenant, or What if Humphrey Bogar…