Lula Wiles: Combatting Erasure One Song at a Time

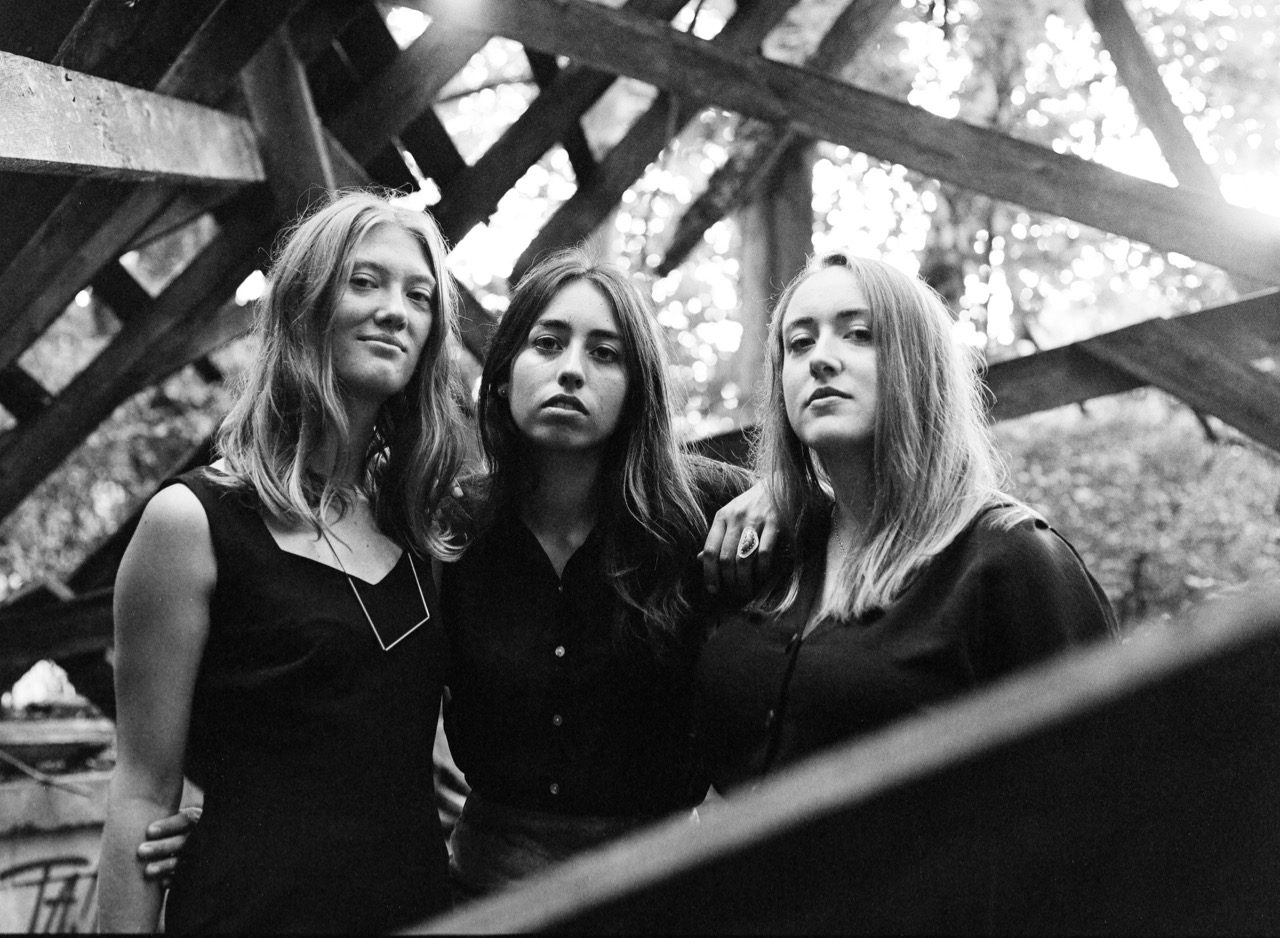

Photo by Laura Partain.

Hello humans! Lula Wiles here, writing to you from Brooklyn. We have decided that 2019 is the year we will take over the world, and that, necessarily, starts with the No Depression homepage! You’ll be seeing a lot of us, as we’re the ND Spotlight artist this month. As we approach the release of our sophomore album, What Will We Do, out on Smithsonian Folkways Recordings on Jan. 25, No Depression invited Mali and Ellie to write a guest column about “anything personal.” (Isa writes a bi-weekly column, so check that out as well!) We’ll be writing about folk songs, where we come from, and why we think it is important to engage with uncomfortable topics as songwriters.

As any touring musician knows, the tour van is a versatile vessel in a band’s life — it is at once a mode of transportation, a therapy room, a think tank, a place to recover from late nights, and, unfortunately, a metal capsule of human stench. We want to bring the ND readership into the Lula Wiles think tank today to discuss a topic we have been orbiting in the van for a while. The conversation starts with the word “erasure.” If you’re unfamiliar with the meaning, here’s an article with a few different definitions!

As an Indigenous person, Mali thinks about this word a lot. “Erasure” is integral to any discussion on Native issues, and it affects our everyday existence. In the van, we often discuss the various shapes that Native erasure takes: It is carried out by schools and universities when they teach false or incomplete Native American history, and by the media when it ignores Native voices. On a smaller/individual scale, erasure happens every time a non-native person wears leather fringe, gets a dreamcatcher tattoo, supports an “Indian mascot,” and so on, as if Native people no longer exist or have feelings. Overall, erasure sees that our stories remain untold.

In addition to being an ethnically diverse band (Mali is Wabanaki, the original Mainers), we are all just rural Mainers. In the communities we are from, “erasure” doesn’t necessarily come up when discussing everyday life. There are many fundamental differences between Native and rural American oppression, and we are by no means equating the two, but we also see parallels. While we have often discussed erasure in the Indigenous context as a band, it becomes increasingly evident that erasure extends beyond ethnic lines. We cannot pretend to represent all of rural America when we speak to these parallels, as rural life is extremely diverse, but we find ourselves returning to the idea of erasure as our experiences growing up in rural Maine inform our songwriting.

We see erasure as a result of power imbalance — in this case the cultural and economic power imbalance between urban and rural America. Because “major cultural centers” are urban, non-urban communities are marginalized by the fact of being isolated from them geographically. As a result of geographic marginalization, rural Americans often have little control over the way the urban-based media represents them, which can lead to cultural and political marginalization. It may be worth emphasizing that the mainstream media is typically curated by and for urban elites. Ultimately, economic, cultural, and geographic marginalization remove rural existence from the national consciousness, erasing the stories of those communities and breeding division along the urban-rural plane.

Misrepresentation creates stigma and stereotypes about and withinrural communities, which feed the power imbalance. For example, when rural hardships like poverty, drug use, and lack of educational opportunities are incompletely depicted and discussed in the national media, these nuanced realities become stigmatized. In effect, ruralness becomes stigmatized.

Wealth worship in the media is also influential in stigmatization. In our hometown, Farmington, Maine, there were clear social and often ideological divisions between the community members who presented themselves as having wealth and those who did not, regardless of the actual amount of money going around. There were certainly class differences, but the way that individuals presented themselves visually often reflected whether they proudly embraced rural culture or were ashamed of it. We have seen “wealth worship” bring judgment and division within our own communities in Maine, and the complex tangle of ideologies and political opinions that follow.

From a birds-eye view, the scenario appears like a culture-war between “pop culture” and “country culture,” driven by elites. But it is much more complicated than a cultural binary, and that is what we want to emphasize when we write about home. When rural people are nationally voiceless, their hardship stigmatized, and their political complexity unaccounted for, diverse rural communities are reduced to stereotypes. The process of burying their stories constitutes erasure.

As a band, this is one reason why we find songwriting so important: It gives us the power to combat erasure. In Lula Wiles, we see music as our platform and megaphone for sharing stories that don’t get heard. The song is a template to process collectively with our listeners. It feels like a superpower, we sometimes joke, that we can infuse catchy melodies with important ideas and stories and get them stuck in listeners’ heads.

Kaia Kater recently appeared on the Basic Folk podcast and spoke about how she delivers “uncomfortable” messages honestly at her shows: “I have this thing I do […] I kind of trap people. So my first set will have no mention of race, and then at intermission people buy my record, they’re super into it, and then in the second set I start to get really heavy and intense and kind of don’t give a you-know-what about people’s comfort, and so I talk about [race] really honestly.”

We don’t take the power of holding an audience’s attention, or “having their ear,” lightly.

On What Will We Do, we hoped to develop our voices more as songwriters, and we ended up confronting uncomfortable topics more than we expected to. We wrote most of the songs within a six-month period in 2017, and we ended up telling a lot of stories about home. Ellie’s song “Hometown” disassembles the stereotypes of rural life (“Your hometown’s shining like a magazine ad […] / But flip the page it’s a broke-down dream”), pulling back the idyllic curtain to talk about poverty, drug use, the complexity of political divisions and the role of the “American Dream.”

“Morphine” talks about how “trauma cycles” progress from generation to generation, and how drug use presents itself as an escape from hard living conditions and family trauma (“The only way out is up / glory train headed straight for the sun”). “Good Old American Values” directly confronts erasure and exploitation (“Indians and cowboys and saloons / It’s all history by now, and we hold the pen anyhow”) of Indigenous people.

Many of the songs on What Will We Do are about the fact that we have all felt erased, or have even erased ourselves. As songwriters, we want to lean into the uncomfortable topics instead of avoiding them, because erasure doesn’t actually get rid of anything. We want to invite the listener into the world of the story, into the life of its characters and the emotion of their experience. Because most people can personally relate to the feeling of being silenced, we can try, through songs, to have empathy and compassion beyond our own experience so that we do not silence others.

* * * * * *

EDITOR’S NOTE: Lula Wiles is No Depression‘s Spotlight artist for January 2019. Don’t miss our feature story about this talented trio, and look for more from them all month long!