EASY ED’S BROADSIDE: Kevin Beasley’s Cotton Gin Music

Kevin Beasley: A View Of A Landscape / The Whitney (Photo by Easy Ed)

Mystery writer Lawrence Bock wrote a series of books based on a former police detective named Matthew Scudder that often made reference to butchers who worked at the meatpacking plants going to Mass early in the morning wearing their blood-stained white coats. That memory came to mind as I recently walked through the Meatpacking District, nowadays a tourist-friendly and gentrified trendy neighborhood in Manhattan. Since the late 1800s, meatpackers have been processing 250-pound carcasses of beef, cutting them up into pieces for restaurants and markets. But it is a dying business, so to speak.

Fifty years ago there were over 300 meatpackers employing 2,000 workers in the small area south of 14th Street near the Hudson River. Today there are only seven companies still in business, all located in the same city-owned rent subsidized building with just 125 workers left. Still considered to be an extremely dangerous job, the industry has come a long way from its history of overworking its people, not having good safety measures in place, and fighting hard and dirty against the unions. By the 1970s, with vacuum packing, refrigerated trucks, and low-cost, non-union jobs, the industry came to be dominated by just a handful of large corporate producers. And the vast majority of workers are Mexican immigrants.

My apologies for taking two paragraphs to get you to where my head was at when I walked into the Meatpacking District’s Whitney Museum of American Art to see Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again, the first Warhol retrospective organized by a U.S. institution since 1989. This promised to offer new work never seen before and it didn’t disappoint. Living in New York allows for a surplus of art museums, and it’s where I do my best music listening. Always going solo with ears covered by headphones, I can spend endless hours wandering around in that euphoric state of jukebox shuffle with my eyes leading me through the galleries and my feet following.

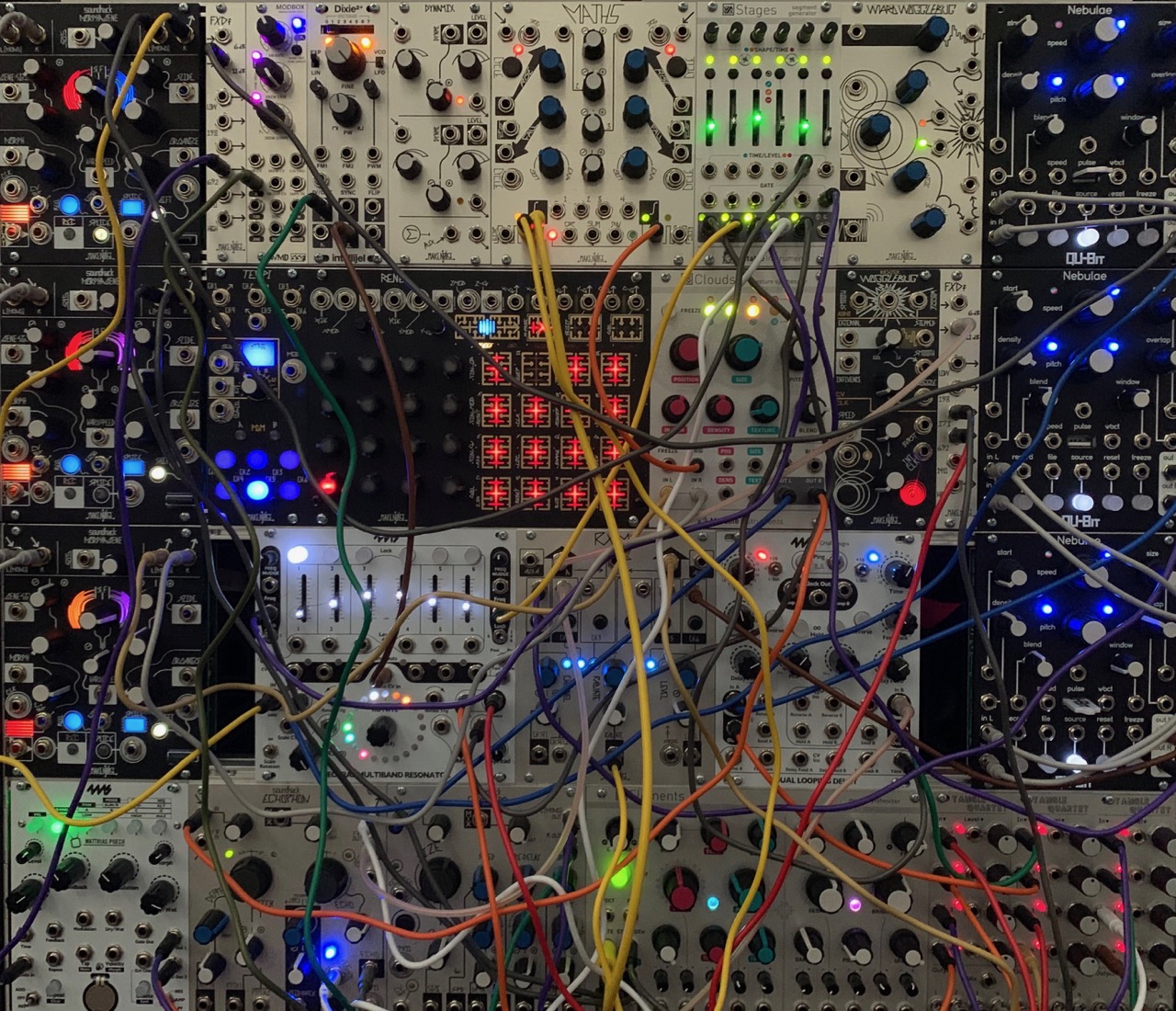

If you count the first-floor lobby, there were three out of eight floors devoted to Warhol, and when I finished with him, I took the elevator up to the eighth floor. As I walked out, this is the first thing I saw: a rusty old motor running, encased in a soundproof glass container. Not bothering to read the notes about what this exhibition was or about the artist, I just stared at the darn thing and noticed that microphones were placed inside the box. Taking off my headphones and interrupting Jelly Roll Morton, I listened for a minute and heard nothing. What a strange use of space, I thought, and I wandered down the hall.

If you just watched that video, at the ten-second mark you might have noticed the large dark room that I walked into on the west end of the gallery floor. Listening to a new song by Phoebe Bridgers and Conor Oberst, I kept my headphones on as I didn’t want to interrupt them. Besides myself in that room, there was a museum worker, one table with audio equipment with a lot blinking lights, several benches, and large black speaker boxes placed throughout. Suddenly beneath my feet I felt a strong vibration that made my legs quiver.

Off came the headphones and I sat down in the center of the room. The sounds were at first quiet and ambient, until they weren’t. The volume rose and fell, the vibrations I had first felt were sometimes stronger and at other times merely a tremor. In equal measures feeling both meditative and musically seduced, my eyes closed and body relaxed. Mechanical sounds through modern electronics now sounded both ancient and future bound.

Kevin Beasley is a 34-year-old artist born in Virginia and now based in New York. That strange contraption I had seen when I exited the elevator was an old cotton gin motor that came from Maplesville, Alabama. In operation from 1940 to 1973, the motor powered the gins that separated cotton seeds from fiber and now, after restoration, it was re-purposed to generate sound as a musical instrument. Here’s the description from the exhibition’s website:

“Through the use of customized microphones, soundproofing, and audio hardware, the installation divorces the physical motor from the noises it produces, enabling visitors to experience sight and sound as distinct. As an immersive experience, the work serves as a meditation on history, land, race, and labor.”

For about 15 minutes I sat alone in the room just letting the rhythm and sounds wash over me, never repeating and creating, on its own, fragments of melodic and dissonant notes. A middle school class of about 30 kids soon entered the room, and I watched as they all sat down on the benches and floor. Expecting them to act like I would have at their age — distracted and noisy — they were quiet as church mice, joining me in soaking in the symphonic distortions.

With a Master’s of Fine Arts from Yale for sculpture and in addition to music and sound creations, Beasley also creates visual works by searching for different materials and then binding them together using substances like resin and polyurethane foam. Some of his work is small, everyday items. At the Whitney he presented several large-format pieces utilizing raw cotton. To my eyes they were equally as interesting and stimulating as the sounds of the cotton gin motor had been to my ears.

Unlike the way technology cut the labor force in the meatpacking industry, the invention of the cotton gin had the complete opposite effect. In order to have enough workers to pick the cotton when it was ready, domestic slave trading ramped up at a rapid pace. With the plantations based in the Deep South, the owners looked to the Upper South, where there was a surplus of workers and more than one million slaves were sold. While in 1790 there were roughly 700,000 slaves in America, by 1850 the number had exceeded three million, with over 27,000 ocean voyages recorded.

By 1860 the plantation-based agricultural system in the Deep South produced two-thirds of the world’s cotton, and after Lincoln was elected president, partly on an anti-slavery platform, Southern states seceded and the Civil War broke out. Some point to the invention of the cotton gin as being the indirect cause of war. In using that motor to create sound, Beasley has added something new and different to the large body of African American spirituals, field hollers, and work songs that grew out of that bleak time period. An example of how art and music can always go back to the roots and harvest a new crop.

Many of my past columns, articles, and essays can be accessed at my own site, therealeasyed.com. I also aggregate news and videos on both Flipboard and Facebook as The Real Easy Ed: Americana and Roots Music Daily. My Twitter handle is @therealeasyed and my email address is easyed@therealeasyed.com.