Box Set Celebrates the Power of Music to Bring Change

Music can feel like magic sometimes. Even if we’re not listening closely, it can stir something deep inside of us. But when we engage with it, we realize, almost in our bones, that music is a survival tactic.

As social animals, we humans quite literally cannot live without one another. Even in these times when we’re told we are so starkly divided (whether or not we choose to actually believe and behave that way), we can recognize that it doesn’t matter to us who everyone else voted for when we gather together at a concert and sing along with our favorite songs. Music has the power to connect us across our differences, assumptions, prejudices, and other fears, and that is the way that it has helped us surmount some of the hardest, scariest, most confusing moments in our history. Indeed, it will continue to play that role, for as long as we’re on this Earth.

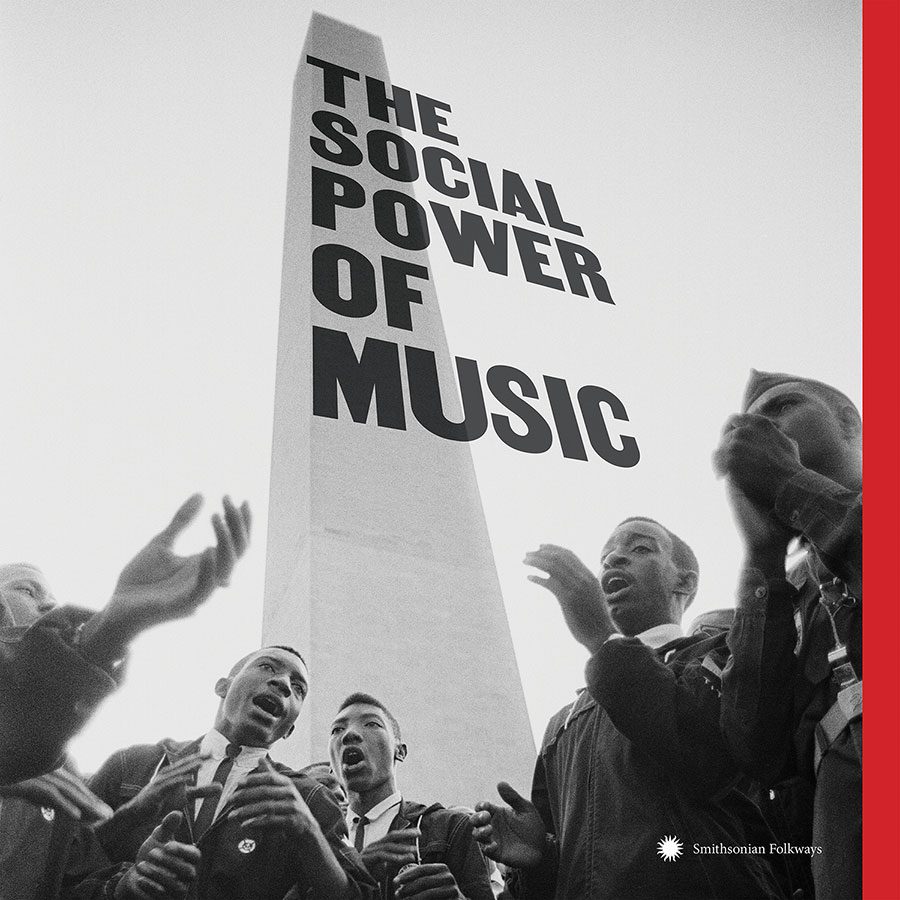

That power music wields is celebrated on a new four-disc box set from Smithsonian Folkways. The Social Power of Music is an 83-song collection that, taken in full, illustrates the way music behaves as connective tissue between us humans, regardless of age, sex, race, language, religion, ideology, or any other perceived difference.

As Disc 1, “Songs of Struggle,” opens, the Freedom Singers lead what sounds like a room full of people singing “We Shall Overcome,” and we can feel the spirit of that song. The way it lives outside of and beyond time. The way the harmony comes in, distant and lingering, almost implied. The way you can’t get into the second verse without wanting to sing along. The way that “we” somehow means all of us, no matter where we are or whom.

The Freedom Singers slow the song down, compared to other recordings by folks like Pete Seeger — a tempo truer to the black origins of the song during the labor movement. But true to the song’s rebirth during the 1960s, they stick to the 12/8 time signature Guy Carawan brought in, even as they sing a cappella.

A casual listener could just appreciate the power of the song, which is plenty. But all of these contributions made to the song by many people over a period of time matter in the context of this being the first song in such a collection.

Few other songs carry such an active history in the social life of American music. No doubt “We Shall Overcome” is the first song that would come to most people’s minds when they consider a collection with this title. Leaving it out would have immediately discredited the collection. Placing it at the beginning, via a recording by the Freedom Singers of all groups, throws down a gauntlet of sorts.

As usual, Smithsonian Folkways isn’t messing around.

All the usual suspects are here: Woody Guthrie, two Seegers (Peggy and Pete), Fannie Lou Hamer, Paul Robeson, The Almanac Singers, Joe Glazer, even Elizabeth Mitchell. But let’s not mistake this for a nod to the folk revivalists. The Social Power of Music is less a snapshot from history than it is an argument that music has always been — and continues to be — a vital presence in our gatherings. The songs here have been pulled from across nearly a century of music’s role in social engagement. Thus, the four-disc set makes the case for music as a timeless, vital tool in the life of humans around the world, be they organizing for change, praying for redemption, or celebrating Mardi Gras.

Disc 1’s songs address all the outcroppings of the American movement: workers’ empowerment, opposition to war, and equality for black people, immigrants, women, indigenous people, and others. It hands us songs that are somber and reflective, songs meant to sing on a picket line or during a march, as well as jaunty, danceable tunes meant for listening, like “Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die,” provocative tunes like “Which Side Are You On?,” exquisite instrumentalism on Spanish language songs like “El Pobre Sigue Sufriendo,” and songs that poke fun at oppressors like “Ballad of the ERA.”

Disc 2, “Sacred Sounds,” opens with “Amazing Grace,” which here does not have the languid melody many of us are used to. Sung by the Old Regular Baptists, the song feels less like a performance than a group meditation. With a song leader calling out the first line of each verse, there is an implicit welcome to social singing — this song is meant to connect people rather than to serve a solo confession.

As Smithsonian Folkways associate director D.A. Sonneborn points out in the disc’s liner notes, “Ritual is among the oldest of human practices.” The songs included here are largely focused around Christian ritual, though there are a couple of notable exceptions: “Kol Nidre” from the Jewish tradition, “The Call to Prayer / Adhan” at Track 9. the Buddhist chants and prayers on Track 11, “Zuni Rain Dance” by members of the Zuni Pueblo, and the rousing “Many Eagle Set Sun Dance Song” by the Pembina Chippewa Singers.

However, if there is a deficit to this collection, it’s the comparative dearth of non-Christian ritual songs on this disc, considering there are hundreds of religions practiced in the United States. Sonneborn addresses this in the liner notes, noting that around 80 percent of Americans ascribe to some form of Christianity and that the Smithsonian collection follows suit on that majority.

Nonetheless, the songs contained herein point at the tendency of human gatherings to employ songs that call for peace and contentment on Earth as well as in the afterlife. They marvel at the natural world, whether they recognize it as the creation of a Christian God or whether they attribute it to other spiritual forces. They call those within earshot to gather in prayer and reverence. Even the Christian songs, like “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” (performed exquisitely here by The Princely Players) and “I’ll Fly Away” (sung by Rose Maddox) can be viewed in the larger tradition of musical ritual, the use of music to pull us out of our human minds and into some more ethereal eternal spirit.

Disc 3, “Social Songs and Gatherings,” carries songs by the mighty Clifton Chenier, Flaco Jimenez with Max Baca, and personal favorite Rebirth Brass Band. We hear more from the exquisite Pembina Chippewa Singers and a sweet rendition of the children’s song “Mary Mack” from Lilly’s Chapel School in Alabama.

This is perhaps the most thematically variant sub-collection in the set, as it includes party and dance songs, wedding songs, love and flirtation songs, children’s songs, a drinking song, holiday song, funeral song, pow wow song, and even a song of patriotic celebration (“The Star-Spangled Banner”). Though many of these tunes tend to be employed by a band or musician performing while others dance or simply sit back and enjoy the music, they are nonetheless songs that are central to some kind of social gathering, where people can relax and forget for a moment about the things that divide us.

Finally, bringing the collection full circle, we have Disc 4, “Global Movements” — a collection of movement music from beyond the United States. If any of the discs in this collection stand out from the others in terms of diversity of context and culture, introducing the average listener to new sounds and traditions that capture a certain spirit of the wider world in which we live, “Global Movements” is that disc.

It presents stirring empowerment songs from across Africa and various Spanish-speaking countries. There are also songs of freedom from Italy, Greece, France, Korea, and elsewhere. The disc opens with another performance from Pete Seeger, which may seem incongruous until we remember that Seeger (who would have turned 100 this year and will be getting his own box set from Folkways) traveled the world collecting folk songs, teaching international movement anthems to Americans long before we had access to them via the internet and collections such as this one.

The discerning folk music fan will be familiar with many of the songs and artists included on most of these discs, but the “Global Movements” entry illustrates that the social power of music isn’t exclusive to America, where we celebrate our movement music all the time. The intentional use of music is, rather, a universal human impulse — as true for South African refugees in Tanganyika as it is for those in Zuni Pueblo as it is for Country Joe McDonald or the SNCC Freedom Singers.

“Without a doubt,” writes ethnomusicologist Deborah Wong in the liner notes for the final disc, “specific songs have become sources for shared vision, and resolve.”

But then she goes on: “The boundaries between the individual and the collective become fluid, which can lead to heightened empathy and bonding, and that in turn can lead to a sense of heightened strength, ability and possibility. When groups of people imagine and actualize community through song, a body politic can spring into being.”

Though Wong writes this to make the case for including an entire disc of international movement music, the same can be said of songs of worship and celebration. After all, any context in which we gather together in search of commonality — whether organizing for political change or celebrating a wedding, expressing gratitude to our god or singing something silly with our classmates — we have an opportunity to recognize through music that we are in this life together. Any way that humankind changes direction or shifts priorities will occur because we connect across our differences in order to make progress.

And while there’s no way to prove that music can change the world on its own, it is certainly an avenue down which we can walk together, toward our better selves and a better world.