THE READING ROOM: Collection Showcases John Hartford’s Mammoth Love of Fiddle Tunes

Although John Hartford might have been best known by the larger public as a banjo player, especially through his appearances on The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour and The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, his fans remember him as a fiddler, preserving old-time tunes and innovating within the tradition of American fiddle music.

He picked up the fiddle as a youngster. His mother took him to see Flatt and Scruggs, and while that exposure to Scruggs sparked a lifelong romance with the banjo, he was equally entranced with the playing of the group’s fiddler, Benny Martin, with whom he later became friends. According to music historian Greg Reish, Hartford once described how his parents would take him along to square dances, where he met the fiddler Jimmy Gray, a local dentist whom Hartford named as one his biggest influences. According to Reish, “At the age of fourteen … John became increasingly intrigued with playing the fiddle, recognizing its place in the music he loved. It was a source of amusement for his family to say that John played the fiddle; for them it was the violin. As early as five or six years old, John had been known to sneak his grandfather’s old fiddle out (he never heard him play it) and scratch around on it.”

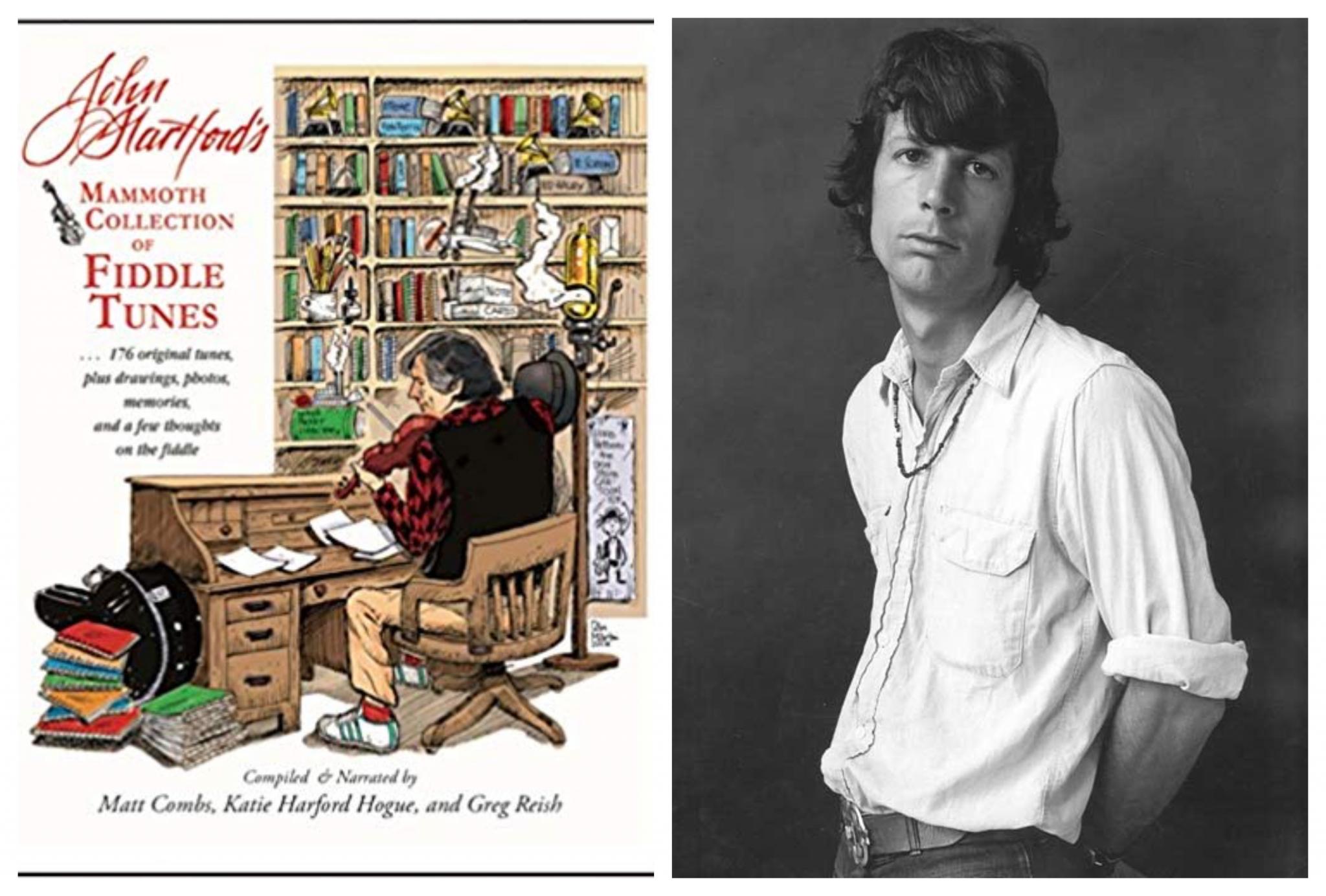

Thanks to Hartford’s daughter, Katie Harford Hogue, Reish, and fiddler Matt Combs, we now have an intimate, detailed, and insightful look at the depth of Hartford’s devotion to playing fiddle and writing tunes for the instrument. John Hartford’s Mammoth Collection of Fiddle Tunes (StuffWorks Press) is chock full of memorable stories about Hartford and his playing, his writing, and his humor. The book features 176 of his original compositions, most of which have never before been published, surrounded by his drawings, his own notes about certain tunes, and his friends’ memories of him and his music. Tune titles range from “Ohio River Rag” and “Howdy’s Uncle Bob” to “Gallatin Road Breakdown.” There’s even a twin-fiddle arrangement for “Gentle on My Mind” included.

This stunning collection reveals clearly how deeply fiddle music consumed Hartford and the great joy he reveled in while playing it. Former bandmate Mike Compton recalls how deeply committed Hartford was to fiddle music, describing Hartford’s approach to playing on stage: “John played all over the fingerboard, sometimes familiar tunes, sometimes his own material in unusual keys such as E-flat. Often John played some things really fast … It seemed like he didn’t care so much about how I played, or well I played. The whole thing was all about just playing stuff that pertained to the music that was coming out of him.”

In the chapter titled “The Man Who Follow His Heart,” his daughter and others reveal that Hartford often came up with names for his tunes simply by following his intuition, by following moments of inspiration as they came to him, no matter when or where. “Although Hartford routinely named tunes for people who were important to him in some way, it may come as a surprise that none of the people interviewed for this anthology knew that John had done that. Of course, we may never know whether John actually wrote those tunes with specific people in mind, as a tribute, or wrote the melodies and attached names to them later. John’s daughter, Katie, remembers as a kid being amused by her father’s approach to coming up with song titles. ‘He used to tell me that “anything you say can be the name of a song,” including what he had just said. It was funny, because it made you start thinking about everything that came out of his mouth as a potential song title.’”

Words from Hartford’s notebooks offer advice, sometimes humorous, about learning to play fiddle: “Get a metronome, learn to play on top of the beat (’cause you probably are already pretty good at playing ahead of the beat) and then when you get comfortable with that learn to play behind the beat, which you can do with a metronome, ’cause it won’t slow down with you, it will hold you up like a good rhythm section should do.” And on performing: “The audience can spot a phony from the back row, whether you’re in somebody’s house or in Carnegie Hall … As long as you’re playing, being straight, and playing music the way you want to hear it played, at least you won’t be wasting your time.”

Hartford loved his family and friends, and his house was always open to musicians and friends who were traveling through. Those moments invariably ended in jam sessions. “John Hartford was a center of attention socially as much musically, a gregarious and friendly man who kept an open door policy at his house, a man who always answered the phone and never seemed annoyed by it.”

As Reish points out in his introduction, John Hartford’s Mammoth Collection of Fiddle Tunes “is the story of John’s lifelong love affair with the fiddle, its music, its people. That story is told through the memories of the people who knew him and shared this love, through the thoughts and observations about fiddle music that John left behind, and, most importantly, through the original tunes that he composed for the instrument.”

John Hartford’s Mammoth Collection of Fiddle Tunes is a collection, an anthology, to be savored in small portions, tasting the flavor of every musical morsel Hartford cooks up. The book is a feast for the senses, and it provides many glimpses into Hartford’s creative genius. As of now, no one has written a biography of Hartford, so the Mammoth Collection of Fiddle Tunes and Andrew Vaughan’s John Hartford: Pilot of a Steam Powered Aereo-Plain (StuffWorks Press, 2013) provide the closest we have for now.