THE READING ROOM: Wanda Jackson’s Stories Assure ‘I’m Still Here’

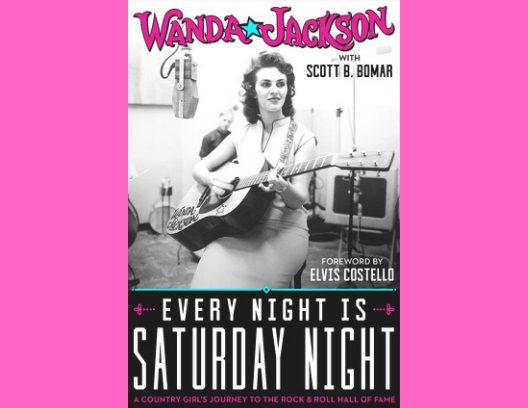

When Wanda Jackson announced her retirement from performing last week, the First Lady of Rock and Roll and the Queen of Rockabilly left us all a bit sad. Her energetic performances, her fiery songwriting, and her dynamic stage shows turned every one of her shows into a rocking party. Back in 2006, even Patti and Bruce Springsteen danced the night away to Jackson’s music at her show at the Asbury Lanes in New Jersey. Yet, though Jackson may be hanging up her stage shoes, she’s isn’t finished sharing her stories with us, if her vibrant autobiography, Every Night is Saturday Night: A Country Girl’s Journey to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (BMG), written with co-author Scott B. Bomar, is any indication. Her final words in the book, which came out in late 2017, promise: “I have many stories left to write.”

Jackson tells great stories — about her days with Elvis Presley, her marriage to Wendell Goodman, her encounters with Jerry Lee Lewis, her first appearance on the Grand Ole Opry, and her first appearance on the little radio station in her town when she was a teenager. Her autobiography provides a rich banquet of her tales, and she offers up some tasty morsels about her life and her music. She’s as entertaining in her autobiography as she is on stage, and she’s candid in sharing details about her family and honest about the few regrets she has. With her sparkling humor and the wink of an eye, she recalls her early desire to become a singer. In the backyard, she liked playing preacher, pacing back and forth and shaking her finger at her friends gathered around her. “I guess I had the performance bug from an early age,” she recalls, “and was already looking for my stage.”

Jackson remembers that the music of the church didn’t move her very much at the time. She writes that it was “pretty reserved,” and that the country music back east was “fairly polite, too.” However, in the L.A. area where she lived at the time, western swing reigned. Her parents didn’t use babysitters very much, so they took their only daughter with them on the weekends to dances. Jackson’s mother and father loved to dance, and they made the rounds of the dance halls in the area, where they would stroll and swing to the music of bands such as Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, Tex Williams and his band, and The Maddox Brothers and Rose, “the most colorful hillbilly band in America,” as she says they were known at the time. Jackson “would stand right in front of the bandstand staring up at the performers all night.” When people at the dance hall asked her what she wanted to be when she grew up, she replied, “I want to be a girl singer.” Looking back, Jackson reflects: “I don’t suppose I really could have been any other type of singer, but that’s what I told them. I knew I wanted to sing, but I also wanted to wear shiny clothes and be pretty and glamorous while doing it!”

When she made her debut on the Grand Ole Opry at the Ryman Auditorium on March 26, 1955, she’d already begun to make her mark as a singer, recording with Decca at Owen Bradley’s studio on 16th Avenue, with Chet Atkins on guitar and Jerry Byrd on steel. She dressed glamorously for that night at the Opry, wearing a “white and tight-fitting dress, with a red fringe at the bottom, a sweetheart neck at the top and rhinestone-studded spaghetti straps that were like a halter.” When Ernest Tubb came to tell her that he’d be introducing her, he told her she couldn’t go out on the stage of the Grand Ole Opry dressed like that. She covered her shoulders with a fringe coat she had, but it left a bad taste in her mouth. To make matters worse, Minnie Pearl, Stringbean, and some other cast members of the Opry were cutting up behind her as she played. When she walked off the stage, she told her father that she’d never come back there again — and she didn’t, for a very long time.

Jackson conducts us on a whirlwind tour of her life: her dates with Elvis Presley and his teaching her a different way of playing guitar that became the foundation of her rockabilly style; her shift to recording gospel albums in the 1970s; her initial fear of Jerry Lee Lewis’ wild streak and her discovery of his gentleness during their visit to a local church service; her induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame; and her recording of The Party Ain’t Over with Jack White. Jackson admits that her most recent album, Unfinished Business (2012), was not her career high point and that she was disappointed with it: “Ironically, it actually left me with unfinished business. I decided soon after it was recorded that I would make at least one more album before I hung it up for good. I just needed to wait for the right moment.”

Jackson concludes her story by reflecting that she wishes she might have spent more time with her children, but that she is the person God made her to be and that she “wouldn’t really change anything about her career.” Although the invitation she issues at the book’s close is now bittersweet — “I hope you’ll come see me when I stop in to perform them in your town. We’ll have one heck of a Saturday night together!” — she’s ever hopeful and optimistic and just as vibrant as she was when she sang her first song at her local radio station: “I’ve been through a lot of changes and many adventures, but, for now, I’m still here. I have the love of God, the love of my fans, and the love of a great family fueling me to continue on as a rock-and-roll great-grandma … which means I’ve got some more songs inside me that are ready to come out.”

Every Night is Saturday Night is a celebration, so any night spent spinning Jackson’s albums and reading the stories she shares in this book is a party.