The Work Is Never Done: Anaïs Mitchell’s Folk Opera ‘Hadestown’ Gets New Life

A page from our Fall 2016 print journal. (Photo on page by Joan Marcus)

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is an excerpt of a story from No Depression’s Fall 2016 print issue, “Speak Up!”, about a pre-Broadway production of the musical Hadestown. The Broadway version, adapted from singer-songwriter Anaïs Mitchell’s folk opera, won eight Tony Awards in 2019, including Best Musical and an award for Mitchell’s score. You can buy the issue with the full story here, and we hope you’ll consider subscribing to our journal for more great music journalism four times a year.

In a year when derivations of folk music have driven two Tony-nominated Broadway shows — Steve Martin and Edie Brickell earned a nod for their banjo-driven Bright Star musical, while Hamilton has employed urban folk music (aka hip-hop) to run away with nearly all the Tonys — singer-songwriter Anaïs Mitchell’s little show on a side street in the East Village may seem like small potatoes. But the show earned praise from The New York Times and packed enough houses that its run was extended twice. Even buzzworthy Hamilton creator Lin-Manuel Miranda dropped in to check it out, then gushed about it on Twitter, calling Mitchell’s music “thrilling” and imploring his followers to “GOOOOOO.”

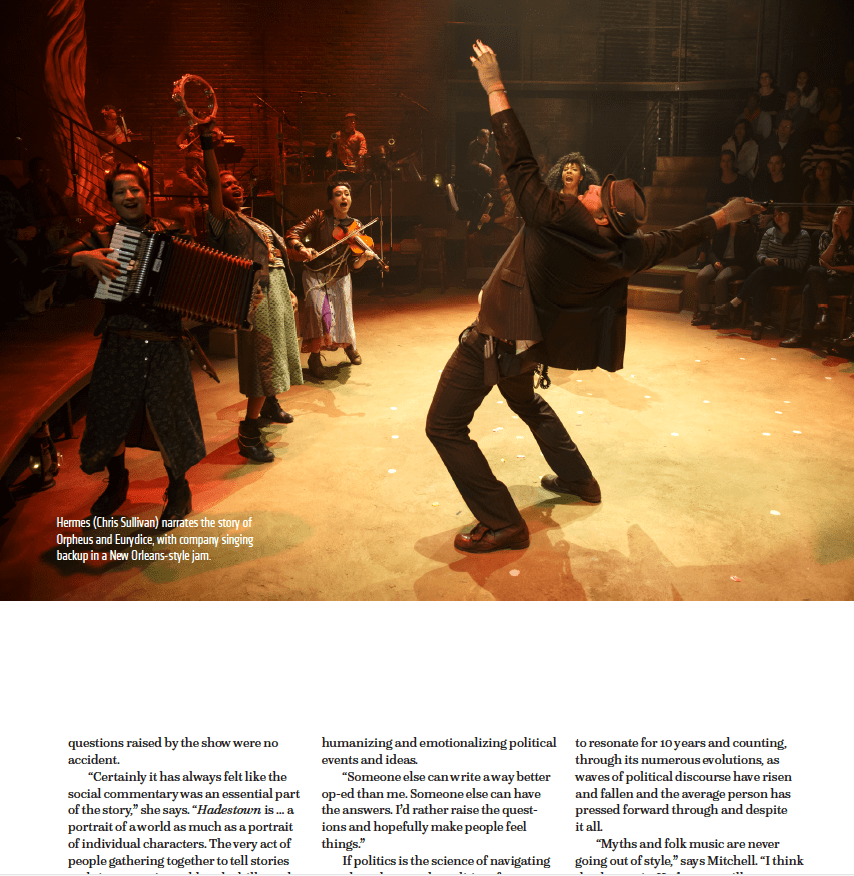

The story of Hadestown is pulled from the ancient myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, a pair of down-on-their-luck lovers who slog through a difficult world with little more than their love and Orpheus’ musical talent to keep them warm and fed. But as winter sets in and the money runs low, Eurydice’s doubt begins to take hold. One day, she encounters Hades, who promises her a life without want if she’ll follow him to the underworld, where he reigns as king. Much as she loves Orpheus, she’s hungry and desperate. She follows Hades, and, before she realizes what she’s done, sells her soul and becomes trapped in his underworld. When Orpheus learns of this, he sets off on a long journey to save her — something he’s only sort of able to do when Hades’ wife and conscience Persephone convinces him to hear Orpheus out. The singer unleashes a song so beautiful and melodic that it sails right into Hades’ heart, reminding him of his core and his humanity. With that musical mirror held to his face, Hades takes pity on the pair of young lovers and lets them head for home, under one condition: Orpheus must walk in front and must never look back to see if Eurydice is following. If he does look back, he will lose her forever.

“You let them go,” sings Persephone, glimpsing her husband’s heart for the first time in a long while.

“I let them try,” he replies.

In Hadestown, freedom is never free.

‘Why We Build the Wall’

Hadestown began a decade ago, when Mitchell was a young singer-songwriter based out of Burlington, Vermont. “The first couple lines and songs I wrote truly came out of nowhere, and just seemed to be about this tale,” she recalls. “The fact that I ever attempted to go ‘all the way’ with writing a full-length piece of musical theater had to do with, a) the crazy challenge … and delight of having one or two hours during which to tell a single story, rather than the three-and-a-half minutes I’m used to in songwriter world. And, b) the truly amazing collaborators I’ve had along the way, including Michael Chorney, Ben T. Matchstick, Todd Sickafoose, Rachel Chavkin, and all of the actors and musicians who have brought the piece to life over the years.”

After a few performances as a “DIY community theater show” in New England, Mitchell had the opportunity to record Hadestown as an album, with producer Ani DiFranco singing the part of Persephone on the disc. DiFranco was able to get her old friend Greg Brown on board as Hades — Mitchell had written the part with him in mind. A chance tour through Europe opening for Bon Iver inspired Mitchell to ask Justin Vernon to sing the part of Orpheus, and the cast was set. Following the album’s release, Mitchell toured the country, delivering Hadestown with rotating casts of local musicians wherever she went.

As is true of all those mythologies, Hadestown’s music tackles sweeping, timeless, universal themes like happiness, fear, love, desperation, and the battle between good and evil, as well as direct issues like the balance of wealth and power and — more specifically — the building of a wall to keep out unwanted people.

“Why do we build the wall, my children?” Hades sings in his guttural growl, like the leader of a cult or a heartless dictator. His workers echo his question before answering back: “We build the wall to keep us free and the wall keeps out the enemy — that’s why we build the wall.”

The song, which falls somewhere toward the middle of Hadestown, and the narrative march on, following a spiral down, through the layers of the underground, separating those inside from those without, establishing an “us” and “them” without need for deep explanation.

In Hadestown, it’s best not to think too critically.

Because we have and they have not

Because they want what we have got …

What do we have that they should want?

We have a wall to work upon

We have work and they have none

And our work is never done

And the war is never won

And the enemy is poverty

And the wall keeps out the enemy

And we build the wall to keep us free

That’s why we build the wall

We build the wall to keep us free

Everything in the song — its rhythm and phrasing and repetitive, plodding melody — feels like a bit of hypnotism. Its twisted idea is almost believable as long as you blindly follow the descending staircase of its logic. It’s a powerful song alone, when Mitchell sings it in her shows — between love songs and tunes about her daughter — as her mousy alto creaks loud like the hinges of an ancient door thrust open, and her eyes fix on a distant point. She becomes a channel for the world of the song, and it can be rhapsodizing even in the most crowded rooms.

“Maybe it’s a folk music thing,” she says. “At some level I’m always after the song that feels like it can walk on its own legs, make its way around the world without needing me to sing it. The idea … that maybe someday the song could exist and no one remembers who wrote it — that’s very inspiring. But it’s actually quite tough to make songs like that that are also capable of doing the work that is required, story-wise, of a dramatic show. That has been a steep learning curve for me in this latest phase of developing Hadestown.”