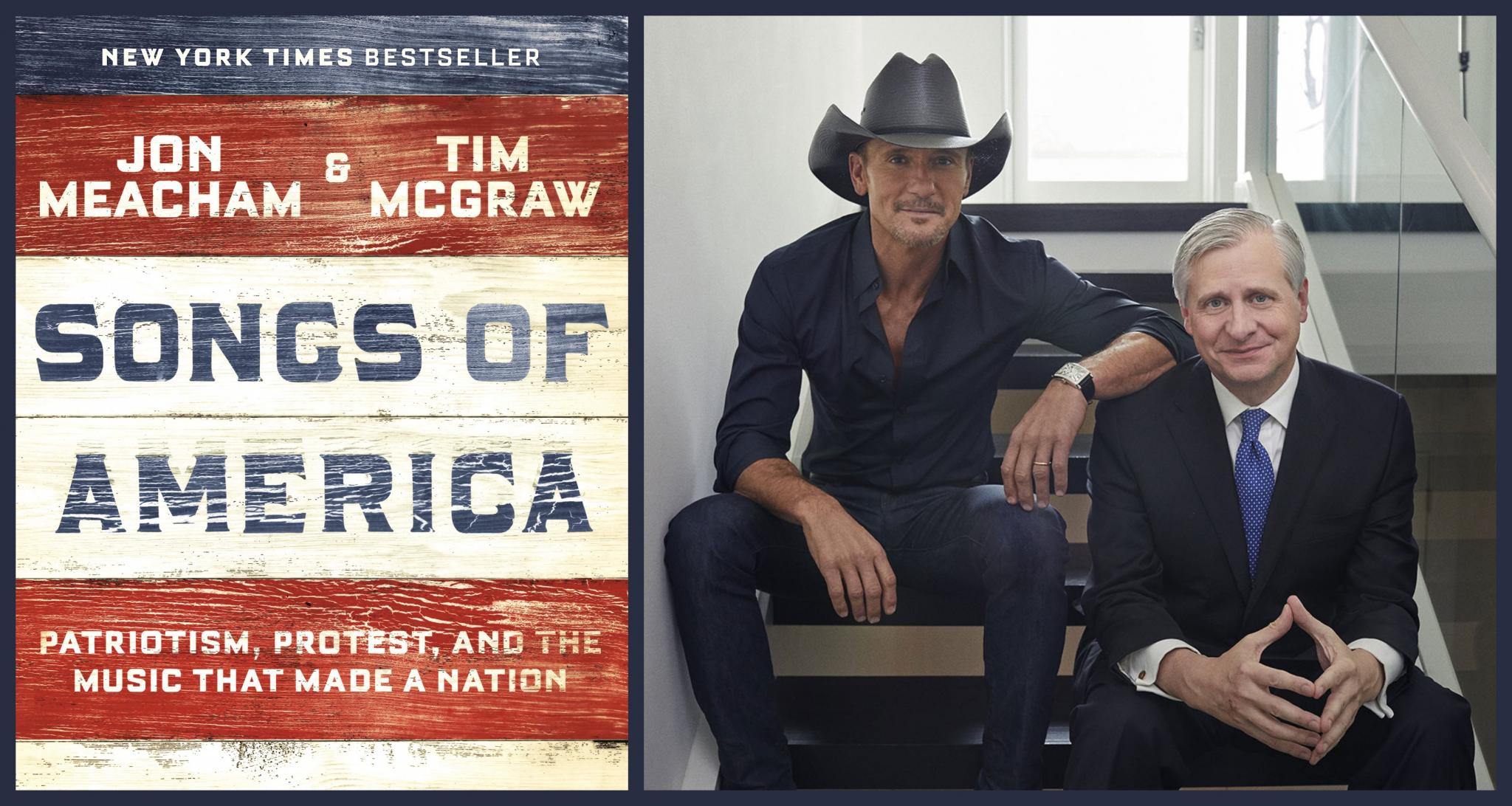

THE READING ROOM: Tim McGraw and Jon Meacham Explore ‘Songs of America’

Author photo by Danny Clinch

On July 4, fireworks burst thunderously over city parks, smells wafting from charcoal grills hang heavy in the air, and music played by high school bands provides the drumbeat and the soundtrack for holiday parades in towns both large and small. There’s all kinds of music marking the celebration of July 4: Plenty of folks will have their favorite tunes blasting out of their radios or boom boxes or car stereos — from hip hop to rock and roll to country — and those songs might be celebrating good times, young love, hot fun in the summertime, or sitting beside a dock and watching the tide roll away. In the parades the songs will likely be familiar tunes that stir people’s hearts, causing them to put their hands over their hearts and stand up as the band plays “My Country ’Tis of Thee” or, nowadays, “God Bless the U.S.A.”

While it’s hard to imagine celebrating July 4 without music, especially the bombastic strains from Sousa marches or “The Star-Spangled Banner,” such music, and people’s reactions to it, does raise questions about how we hear music and how it reflects and shapes our cultural and political values. Should we stand when a band plays “The Star-Spangled Banner” or “America” or “Dixie” or “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and why? Does sitting through the tunes make us less patriotic? Do we know why we’re standing when a band strikes up one of these songs? Of course, simply by asking those questions we’re admitting that music stirs us, calls forth emotions, leads us into action, whether or not such action marginalizes others and elevates us. While many people may stand when the local band marches by, many others living in the same town will be going hungry and homeless. The patriotism evoked, and invoked, by the music of America often fails to account for the lack of liberty and justice felt by so many yet promised by the authors of the Declaration of Independence that the July holiday supposedly celebrates.

One day recently two neighbors in Nashville — award-winning author Jon Meacham and country singer Tim McGraw — just happened to be talking in their front yard about some of these very issues. Meacham had just told the story of “the soul of America” in his book of the same title, and McGraw chimed in to observe that you could tell about the soul of America by telling the story of its music and the ways it shaped the nation’s soul. The two ended up collaborating on a book, Songs of America: Patriotism, Protest, and the Music That Made a Nation (Random House), released with little advance fanfare a few weeks ago.

In eight short and fast-paced chapters, the authors tell the stories of the songs that shaped America, from the “The Liberty Song” of 1768 and “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” to “We Shall Overcome,” “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” “Born in the U.S.A.,” and “This Land is Your Land.” Meacham wrote the narrative sections of each chapter — and included generous selections from the songs about which he’s writing — while McGraw wrote little sidebars in which he reflects on some of the songs covered in each chapter.

Songs of America doesn’t go into great depth either on particular moments in American history or about the history of the songs that shaped those moments, and McGraw’s mostly brief comments don’t often go far beyond the surface of his reflections on a song. For example, on “The Star-Spangled Banner,” McGraw writes, “There is a majesty, a pride, and an elevation we feel in our souls when we hear ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’ It may sound expected or even corny, but when I hear the national anthem I feel the honor — and the obligation — of being an American. … The song leads us to think how far we’ve come, where we are, and how diligent we must be to continue moving forward. The anthem isn’t about martial glory or bombastic nationalism; it’s really a song informed by nervous longing.” On Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” McGraw reflects, “some of the most powerful songs let you fill in the gaps, leaving intentional space in the words or thoughts or unusual phrases that challenge the listener to think and reflect. There is huge power in that.”

Nevertheless, Songs of America is a bit of a primer, whetting our appetites for more. The beauty of the book is that Meacham and McGraw demonstrate that patriotism and protest are two sides of the same coin and that the songs that have shaped America most deeply are those that have bubbled up out of the fervent desire to embrace and enact the promise of liberty and justice for all. As the authors point out: “America is about debate, dissent, and dispute. We’re always arguing, always fighting, always restless — and our music is a mirror and a maker of that once and future truth. … The whole panoply of America can be traced — and, more important, heard and felt — in the songs that echo through our public squares. And if we can hear and feel how the other guys hear and feel, we’re better equipped to press on toward a more perfect union.”

On July 4, 2019, the hope of a perfect union never seemed more out-of-reach. In 2019, disunity and strife mark the public square, and too often one side of the conversation turns a deaf ear to the other. Perhaps music can shape a culture, but we need to listen to the many voices that raise their songs — songs of terror, songs of loss, songs of pain, songs of love, and songs of hope — so we can hear the strains of harmony in the midst of cacophony.