THE READING ROOM: Ben Folds Book Shares Dreams, But Not Details

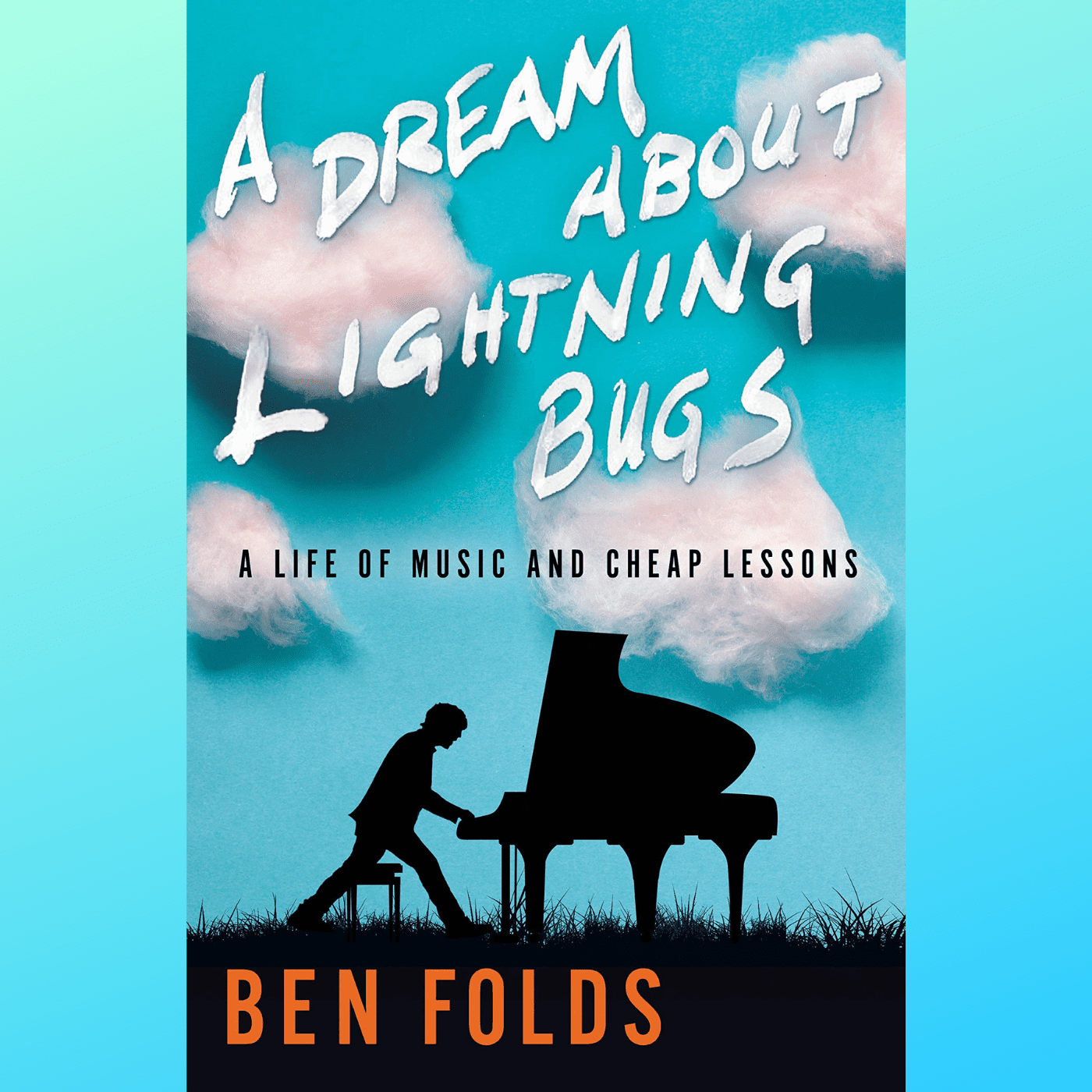

Anyone looking for intimate details about the personal life of North Carolina musician Ben Folds won’t find many of them in his new reflection on his life in music, A Dream about Lightning Bugs: A Life of Music and Cheap Lessons (Ballantine).

Of course, he weaves in a few details here and there about his growing up in Greensboro, North Carolina, his years at the University of Miami, and his early days of making music in Nashville. Yet, in his staccato prose, he’s far more interested in discovering the intricacies of music and writing songs than he is about telling us about his four marriages or his saving of RCA Studio A in Nashville in 2014 (or his decision to leave Studio A in 2016). In fact, quite mysteriously, he leaves the entire story of RCA Studio A out of the book completely. He divides the sections of the book into sections of a song — “intro,” “verse one,” verse two,” “the bridge,” “verse three,” and “outchorus.”

In the intro to the song of his life, he shares the dream that provides the book’s title. When he was three, he dreamed of a jar of fireflies. The dream, he writes, “reflects the way I see artistry and the role of the artist. At its most basic, making art is about following what is luminous to you and putting it in a jar, to share with others.” Yet, not everyone can bottle light, according to Folds, and it is the province of the artist to capture this luminosity. “We all see something blinking in the sky at some point, but it’s a damn lot of work to put it in the bottle. Maybe that’s why only some of us become artists. Because we’re obsessive enough, disciplined enough, or childish enough to wade through whatever is necessary, dedicating life to the search for these elusive flickers, above all else. Who knows where this drive comes from? Some artists, I suppose, were simply cultivated to be artists. Some crave recognition, while others seek relief from pain or an escape from something unbearable. Many have a knack for making art. But I’d like to think that most artists have had some kind of dream beneath the drive, whether they remember it or not.”

Folds also reflects on the social power of music: “Stand in as many pairs of shoes as you can manage, even ones you consider reprehensible or repulsive — even if it’s just for a moment. If you’re going to be a tourist, be a respectful one. Observe, report, imagine, invent, have fun with, but never write “down” to a character. … Position yourself upon a bedrock of honesty and self-knowledge, so that your writing comes from your own unique perspective. Know where you stand and what your flaws are. …Then you can spin all kinds of shit and all the tall tales you like. It’s art.”

A Dream about Lightning Bugs: A Life of Music and Cheap Lessons is chock full of reflections on many facets of Folds’ career as a musician, including his making the piano a centerpiece of his rock and roll. “The piano’s place in rock and roll has always been interesting to me. Its associations with being middle-class living room furniture, church-choir accompaniment, a classical or jazz instrument, make the instrument nearly antithetical to rock and roll itself. The music and culture of the piano symbolized the very thing that rockers were rocking against. Anyone who’s ever rocked the piano has had to be somewhat irreverent and even violent toward their instrument in order to be accepted in the world of rock and roll. You must sacrifice your piano to prove your rock-ness.”

Folds’ peripatetic prose grows most luminous when he considers the freeform character of songwriting and of his own music. He applies such lessons to his life as well to his music, since we have the impression from reading his book that he’s always making it up as he goes along, whether it’s in daily life or in songwriting.

“It’s one thing to take risks playing music, where unpredictability is often rewarded, and another to take them into everyday life, where consequences are real,” he writes. “People often ask me if it’s scary to make up a song onstage, dictating parts, on the fly, to a full orchestra. Well, no. It doesn’t occur to me to worry about that. I have a jazz musician’s view of mistakes. If you play a wrong note, you can always make the same mistake again on purpose and make it sound right. Insistence on the mistake can be quite musical. Indeed, ‘once is a mistake, twice is jazz,’ a quote often attributed to Miles Davis.”

A Dream about Lightning Bugs: A Life of Music and Cheap Lessons is often frustrating and sometimes disappointing. Its very style also functions to undermine it, since the book too often reads as series of disparate stories, connected only by Folds’ need to apologize for his rude public behavior and his attempts to explore the facets of making music. Folds’ legions of fans will love the book since they can’t seem to get enough of their musical hero. At the same time, Folds’ refreshing insights into the life of songwriting will reward readers who aren’t fans.