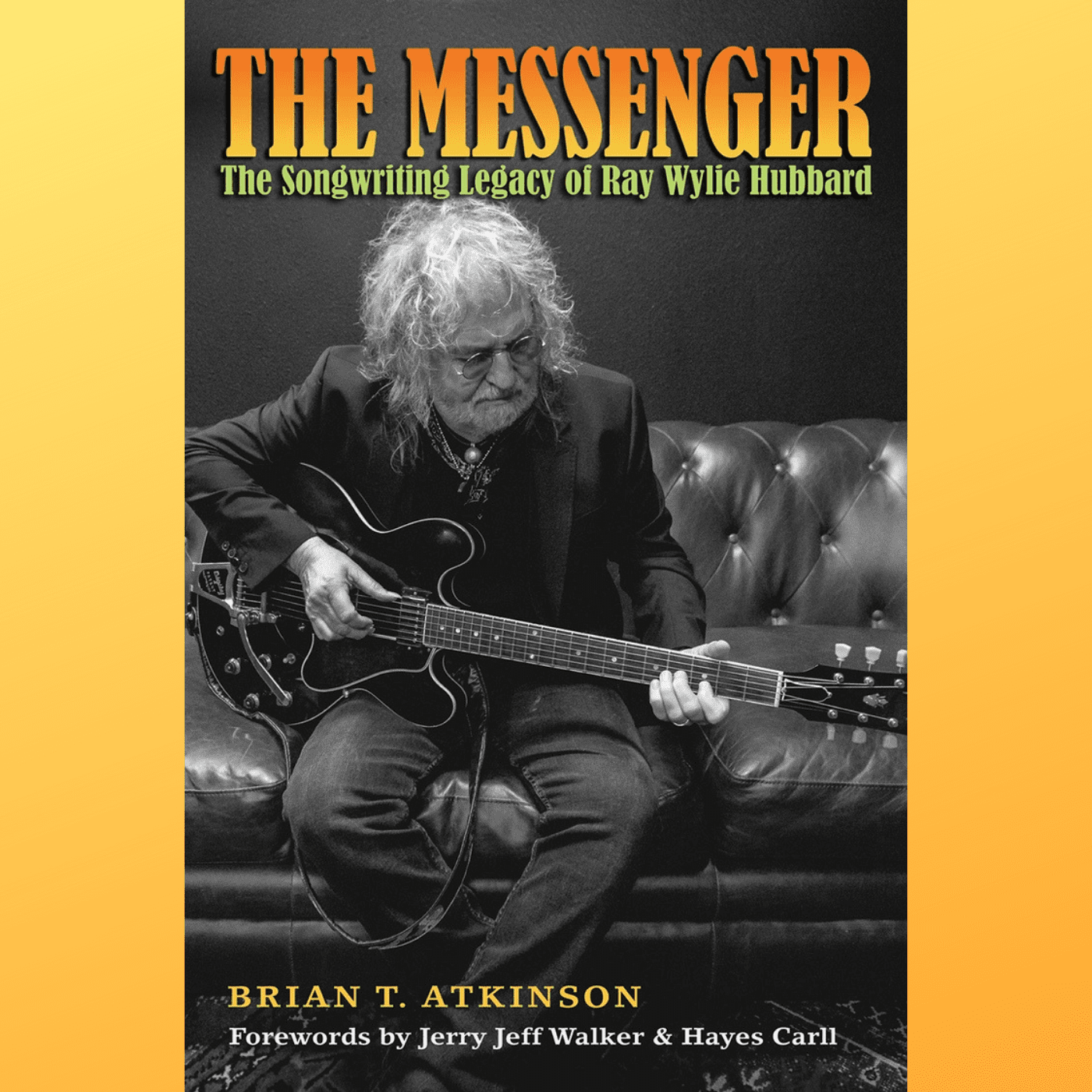

THE READING ROOM: Songwriters Celebrate Ray Wylie Hubbard

A few years ago, Ray Wylie Hubbard reflected on his life and the evolution of his songwriting and music in a humorous, candid, and cinematic memoir a life … well, lived (Bordello Records). He told the now-famous story — which he repeats in the introduction to The Messenger: The Songwriting Legacy of Ray Wylie Hubbard (Texas A&M) — of how he came to write the song that’s hung like an albatross around his neck: “Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother.”

One night Hubbard and a bunch of his friends were hanging out, just passing around an old guitar, running low on beer. His friends picked him to go out and buy more. He could go to the D Bar D, “which was known as the hardcore-cowboy-redneck-right-wing-pro-war-anti-hippie-bar,” or he could go to “the Red Onion Bar at the Village Inn Motel where a long-haired musician could buy a beer.” Hubbard asks himself how bad the D Bar D could really be, even though no longhair had ever gone into it. He walks in and requests two cases of Miller High Life. The rednecks at the bar taunt him and are ready to kick his ass, but an old woman sitting at the bar tells them to let him go. He buys the beer, returns to the cabin, and his friends pass him the guitar: “I hit the G chord and sang, ‘He was born in Oklahoma …’” And “Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother” was born.

The ironies of this story illustrate the core of Hubbard’s memoir, and the focus of The Messenger, Brian T. Atkinson’s page-turning collection of artists’ reflections on Hubbard and his influence on them: Hubbard’s songwriting. In his memoir, Hubbard reveals the spiritual intensity of his commitment to songwriting: “After one demoralizing night,” he writes, “I went home and meditated. After my thoughts quit racing and kind of smoothed out, I opened my eyes and made a commitment to respect whatever creative spark was within me and no matter what, I was going to write songs without compromise and align my purpose with some energy that I believed honored my faith in it to do what I thought would be beneficial to the other human beings walking around on this planet.”

In The Messenger, Atkinson gathers the reflections of more than 70 songwriters —including Mary Gauthier, Kinky Friedman, Michael Martin Murphey, Hayes Carll, Liz Foster, Elizabeth Cook, Eric Church, and others — to confirm Hubbard’s legacy not only as a songwriter but as a mentor and teacher and guiding spirit. In his introduction, Atkinson points out that “Hubbard has been overlooked in the conversation about great Texas songwriters for too long. He shouldn’t be passed by. As several dozen songwriters within these pages proclaim, Hubbard has created a catalog over the past four decades deserving mention among monumental tunesmiths such as Guy Clark, Steve Earle, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Kris Kristofferson, Mickey Newbury, Billy Joe Shaver, and Townes Van Zandt.” The book arranges the collections so that it traces Hubbard’s songwriting from his earliest work relationships with writers such as Bobby Bare or Jerry Jeff Walker to his influence on a contemporary generation of songwriters such as Jeff Plankenhorn and Chris Robinson.

The beauty of these collected reflections shines in their focus on Hubbard’s later work; almost every one of the songwriters agree that “Redneck Mother” is the song they least associate with Hubbard, citing instead “Snake Farm” or “Drunken Poet’s Dream” as models of his ways with language, irony, and storytelling as well as his simple, but hard to imitate, musical style.

Rodney Crowell zeroes in on Hubbard’s poetic language: “When you whittle down a song like Ray, you better have your language together. You can’t hang paper on that thing. Your couplets have to be really succinct, and you can’t have soft rhymes when it’s down to one-chord blues. I talk about the poetry of Ray Wylie because his language has developed over the years to where he can bring it with that gravity. He has this tune (‘God Looked Around’ from Tell the Devil I’m Gettin’ There As Fast As I Can) that basically rewrites the story of Adam and Eve. It’s perfect, with not a word out of place. He somehow makes colloquial language span three thousand years. How do you do that?”

Paul Thorn describes the spiritual intensity of Hubbard’s songs: “I heard Ray Wylie Hubbard name-checked me on Tell the Devil I’m Gettin’ There As Fast As I Can, which is pretty cool. … I remember I went cuckoo over Ray’s music when I saw what he did. He became one of my favorite writers and an influence on me as a writer. I learned a lot of my writing style from him. I like that Ray Wylie has a killer groove, and there are lots of biblical references in his songs. They’re not gospel at all, but he references the Bible a lot. I relate to that growing up a preacher’s kid, and that’s in my music a lot.”

Kelley Mickwee describes her experience of writing with Hubbard and his lessons about songwriting: “Ray’s patient with songwriting and will let you throw out all your ideas. He always told me when I’m asking for songwriting advice that’s there’s inspiration on every corner. … He gives this rap where he says, ‘Never second-guess your inspiration. Write it all down. Get it all down. It’s okay to rewrite, but when inspiration hits, don’t edit at that time. Have it be a flow. You write and edit later.’ Songs are always being edited right up until the moment they’re being recorded.”

Hubbard’s guitar playing is often overlooked. He learned a style of finger-picking from the great blues guitarists Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb that he continues to weave around his lyrics, and he’s also written songs around a single chord. Aaron Lee Tasjan focuses on the genius of Hubbard’s guitar playing: “His guitar playing is very rhythmic and understated, a perfect vehicle that creates this beautiful bed for him to lay his voice and lyrics on. The heart of his band when he plays live is his rhythm guitar-playing. … He’s a guitar hero for guys like me, but he doesn’t play the things you’d normally think a guitar hero would play. He’s not flashy. He plays the truth.”

Judy Hubbard, Hubbard’s wife and manager, recalls their first meeting: “I was smitten with Ray long before I met him. He used to play at Mother Blues [in Dallas] when I worked there, and I’m sure we talked because I introduced him to [Jimmy] Buffett one night when Buffett was playing Mother Blues. … I went to see him at Poor David’s Pub in Dallas with friends when I was thirty, and I specifically remember him playing ‘Portales.’ I was blown away. He was so funny. I said, ‘I’m gonna marry that guy.’ I went over and stood by the backroom doorway, and he came out. I was looking nonchalant like I wasn’t there to meet him. I guess had seen me at the AA meetings, too, and he asked if I wanted to go to a show at the White Elephant in Fort Worth the next day. I did, and we’ve been together ever since.”

Lucas Hubbard, who plays guitar in his father’s band, illustrates how deeply his father has influenced him, both as a guitarist and as a musician: “I take guitar playing one day at a time. I don’t have any expectations of myself where I need to follow in my dad’s footsteps. I’ve always really wanted to create my own name instead of just being Ray Wylie’s son. I love playing, and it’s obviously my dream to continue playing guitar and make a living out of it, but I’ve been so spoiled growing up with such musicians and gigs that I will never want to start playing just to play where it’s not fun anymore.”

The Messenger certainly accomplishes its purpose, for it reminds us, in case we’d forgotten, that Hubbard stands alongside Clark and Van Zandt and Earle as a songwriter whose images, language, and musical style have deeply touched the musical styles and songwriting of a few generations of songwriters. An album, The Messenger: A Tribute to Ray Wylie Hubbard (Eight 30 Records) will be released this week, same as the book, and features many of the songwriters whose words are collected in the book offering their own versions of their favorite Hubbard song: Rodney Crowell, “In Times of Cold”; Bobby Bare, “Snake Farm”: The Band of Heathens, “Drunken Poet’s Dream,” among others.