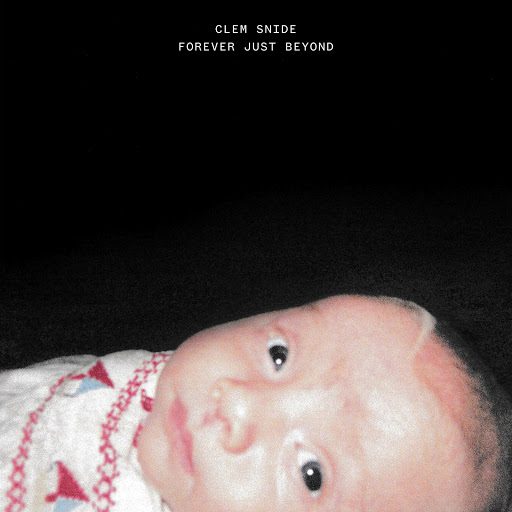

Clem Snide Grows into New Phase of Life and Music on ‘Forever Just Beyond’

I hope you’ve already seen The Good Place, because there’s a potential spoiler below.

Near the end of the show’s final season, William Jackson Harper’s character, Chidi, and Kristen Bell’s Eleanor are discussing mortality, and Chidi shares a Buddhist conception of death that compares a living being to an ocean wave.

“You can see it, measure it — its height, the way the sunlight refracts when it passes through. And it’s there, and you can see it, and you know what it is. It’s a wave. And then it crashes on the shore and is gone, but the water is still there,” Chidi tells Eleanor in the poignant scene. “The wave was just a different way for the water to be for a little while.” It’s the kind of compassionate philosophical meditation on mortality that enabled The Good Place to transcend the sitcom format — and, frankly, the television medium — and become something literary and great.

Clem Snide’s new Forever Just Beyond exists in the same territory. Death is absurd, terrifying, mystifying, inevitable, and a little funny, but not much. There’s levelheaded maturity and even daresay acceptance of our collective fate that songwriter Eef Barzelay, who could be a bit of a goof on earlier albums, seems to have gained over the five years since his last Clem Snide LP. Indeed, these were hard years, defined by crises: Barzelay’s marriage floundered; the songwriter faced bankruptcy. Accordingly gone is the fuzz and much of Clem Snide’s bounce. On the Scott Avett-produced Forever Just Beyond, Barzelay is a gentle indie-folk philosopher that, like Chidi, will share a couch with us and talk those hard existential talks with patience, gravity, humor, and grace.

“To be blessed is always to be cursed as well / dark matter holds it all in place / so when we grind against it, let’s keep our angles true / our bodies bend the empty space,” Barzelay sings in “The Stuff of Us,” translating the breaking wave metaphor into quantum physics. When our wave breaks, our particles return to the fabric of the universe — or, as Barzelay sings with reassuring pep, “The stuff of us / that’s most real / is eternal and free.”

Elsewhere, on the upbeat but troubled “Don’t Bring No Ladder,” Barzelay simply declares, “we are the wave endlessly breaking.” In terms of songcraft, economy of language builds a conceptually complex (though accessible) album. Sonically, this is a gentle and largely acoustic LP, with the occasional psychedelic swirl bolstering metaphysical musings, such as on the title track or the gorgeous, bittersweet “Roger Ebert.”

Taken as a whole, Forever Just Beyond is a balanced document, which allows Clem Snide to tangle with heavy, hard-to-resolve themes without overwhelming the listener. Some songs are just about life and living. Standout track “Sorry Charlie,” for instance, is a breakup song to getting wasted (and to the narrator’s drinking and smoking buddy). “I got a good job now / no, I am not to quit / gonna leave it well enough alone / maybe make it stick / no need to burn it down / maybe start heading home / and not the hazy places where you might have left your phone,” Barzelay sings. “Sorry Charlie / we can’t party / anymore.”

“Denial” and “Ballad of Eef Barzelay” reveal the songwriter at perhaps his heaviest. “Once when I was young I even dared to think / that I could take my own life if I chose,” Barzelay sings on “Ballad.” He could never do it, but the admission sets up an especially stark acoustic number. “I took that trust fall backwards / I just ignored those howling sounds,” he sings on the bleak chorus. “As I kept on falling / I came to realize / I finally realized there was no ground.”

By pure coincidence, Forever Just Beyond came out when it could potentially have the strongest impact. Let’s be honest, with the virus working its way across the globe so many of us are thinking about mortality in clear and present terms. It was always in this album’s DNA that it would address death without dwelling on it and life without pretending it’s perpetual. It’s pure circumstance that the new Clem Snide emerged in a world freshly terrifying and strange, where gentle existential musings drawing from the wells of spirituality, philosophy, and even quantum theory are as necessary as it gets.