Toil and Trouble: Uncle Tupelo’s ‘No Depression’ Turns 30

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the first in a two-part series marking the 30th anniversary of Uncle Tupelo’s debut album, No Depression, which was released on June 21, 1990. Check back Monday for the second part, a roundtable of artists and music industry insiders talking about the album, the band, and the legacy.

Over the last few decades, it’s becoming increasingly harder to talk about the life and legacy of Uncle Tupelo without the conversation falling down one of the many rabbit holes of the band’s ever-expanding mythos.

By now, most everyone knows the more substantial high points of the band’s dynamic yet short-lived arc. Founding members Jay Farrar, Jeff Tweedy, and Mike Heidorn started playing together in high school in a mid-’80s Belleville, Illinois, band called The Primitives that eventually became Uncle Tupelo after their lead singer (Farrar’s brother, Wade) quit the band and headed to college. The trio played heavily around Illinois and Missouri (especially at St. Louis staples Cicero’s and Mississippi Nights), eventually got an indie label record deal, released three celebrated albums, expanded to a five-piece, got picked up by a major label, released their fourth album, and subsequently imploded due to the mounting creative differences and personal tensions between co-frontmen Farrar and Tweedy. In the aftermath of Uncle Tupelo’s breakup, both artists went on to form the highly influential (and still going strong) bands Son Volt and Wilco, while their original work with Uncle Tupelo has garnered the legacy of being —depending on whom you ask — either just one of a number of genre pioneers that carried forward older music to younger generations or the standalone patient zero for the entire alt-country/Americana/modern roots music movement.

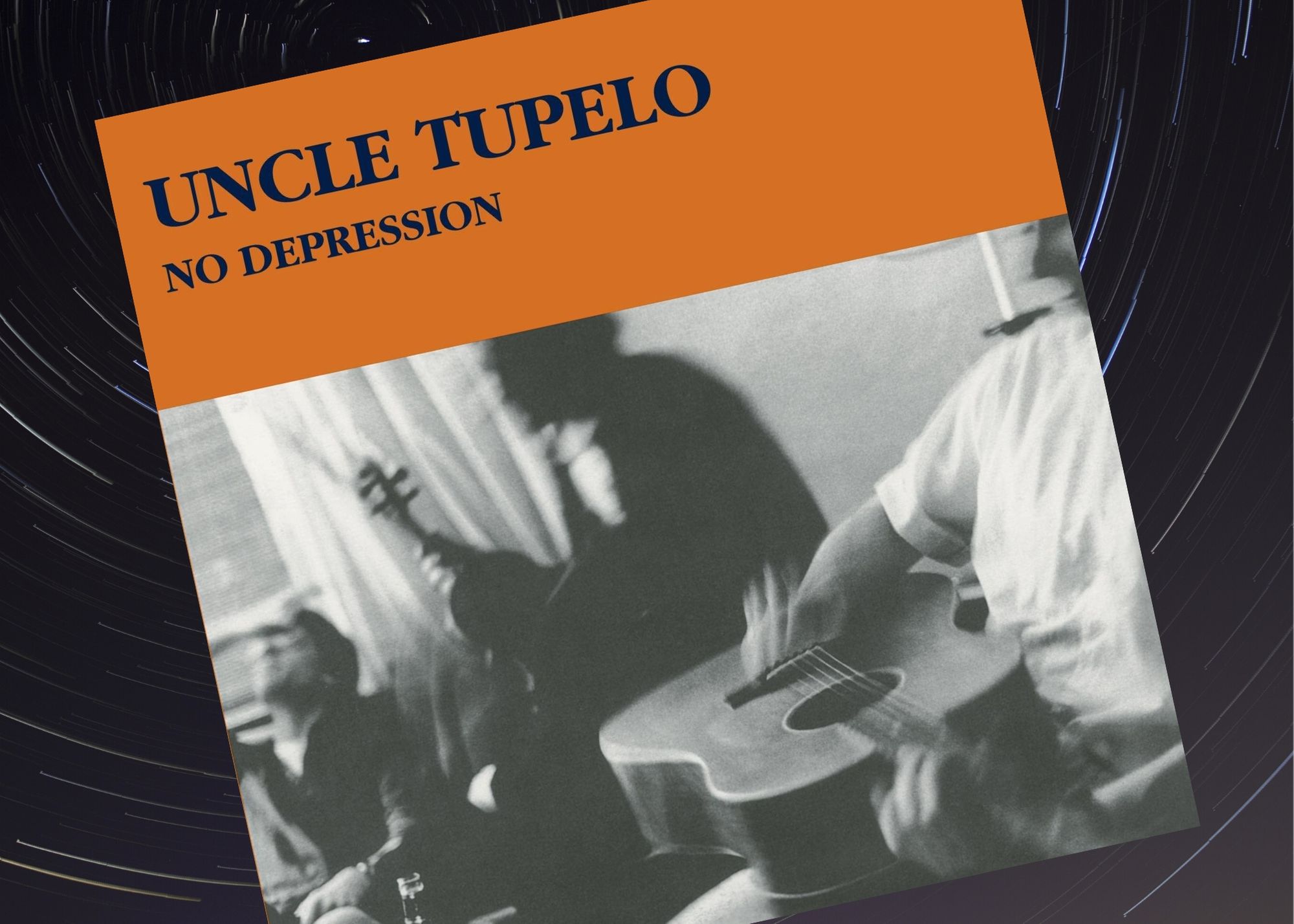

However, on this occasion, the 30th anniversary of Uncle Tupelo’s debut album, No Depression (released June 21, 1990, on Rockville Records), there will be no attempts at encapsulating all of the “which came first, the genre or the band” equivocations. Instead, we decided to mark the milestone with some specificity, foregoing the conventional family tree retrospective in favor of a reflection on what is arguably one of the most shadow-casting records of the 20th century. To do so, we went directly to the source, speaking with Jay Farrar and Jeff Tweedy to get their insights and recollections on three decades of their career-starting (if not career-defining) debut release.

“Has it only been 30 years?” laughs Tweedy, a little stunned, a little tongue-in-cheek. “Like most important events, it somehow simultaneously feels like a lifetime ago and also … boy, that went fast!” Perhaps underscoring the “opposites attract” theme that is at the most foundational level of their complexly layered relationship, Farrar’s reaction to the anniversary is delivered with a bit more middle-of-the-road measuredness: “Honestly, some time has passed but it doesn’t really feel like it’s been that long. It’s just gratifying that anyone wants to talk about what we did 30 years ago.”

While that last comment might elicit a chuckle from anyone familiar with the everlasting supply of appreciative wistfulness and heated debates that has surrounded the individual and collective impacts of Farrar and Tweedy within the roots music community, there is a point to be made about the “subject to change” legacies of landmark albums and the fickle nature of pop cultural attention spans. There will always be a certain element of musical fandom that is asking “What’s next?”, while another, competing thread is turning the conversation from present-day movements back to the music that came before them. In the case of Uncle Tupelo, and especially their No Depression album, the attempt to address both can be found in their unconventional hybrid of self-penned songwriting and encyclopedically referential musical influences that were blended together in ways that allowed the band to function as both creators and conduits.

“We didn’t come up with that whole ‘Woody Guthrie meets Hüsker Dü’ thing. That was probably some publicist along the way,” Farrar says. “Although, it wasn’t that far off. We were fans of Hüsker Dü and certainly there were musical similarities. Lyrically, from Woody Guthrie and essentially Bob Dylan too, we were inspired to think about societal issues and what was going on around us. So, we just put all those things into our songs.” Prime examples of this amalgam can be found on No Depression tracks like “Graveyard Shift,” “Factory Belt,” “Outdone,” and “Train,” where the band mixes the growling guitars and aggressive start-stop rhythms of their punk and indie rock influences with the country and folk-influenced lyrical themes of working-class desperation, economic struggle, anti-war sentiments, down-and-out isolation, and alcohol-soaked small-town blues.

“There were lots of bands — X, The Knitters, Jason and the Scorchers, Green on Red, so many more — already kind of fusing these two worlds that we were straddling,” says Tweedy. “I think our approach to it might have been a little bit more isolated and unrefined. Maybe it came out more punk rock or something, but I think anybody that credits us with inventing anything is wrong.” To further make the point, Tweedy points to the genre-blurring activities of some of his favorite ’60s bands: “We thought there was something boldly punk rock about The Flying Burrito Brothers and The Rolling Stones. To us, The Beatles covering Buck Owens was country rock. So I really resist the urge to believe our own hype.”

Shortly after inking a record deal with Rockville Records in late 1989, Uncle Tupelo kicked off 1990 by traveling to Boston in the dead of winter to record their debut album at Fort Apache recording studio with famed alternative/college rock producers Sean Slade and Paul Kolderie. At the time, the celebrated production duo had already amassed an impressive recording resume that included Pixies, Dinosaur Jr., Throwing Muses, Blake Babies, and more. (After recording No Depression, Slade and Kolderie would go on to produce Uncle Tupelo’s second record, Still Feel Gone, as well as multiplatinum albums for Radiohead, Hole, The Mighty Mighty Bosstones, and others).

“Of all the records that Paul and Sean had worked on to that point, I think the Dinosaur Jr. stuff would probably have been the biggest persuader for us,” admits Tweedy. “Being a production team that had worked on records that we actually owned, I think we were really surprised that they would want to work with us. I remember running through the first take of whatever we tried to do on the first day in the studio and Paul coming out and saying ‘Oh, good. You guys can play.’ I don’t think anybody had ever said that to us before.”

“As soon as we met Sean and Paul, there was such a good working camaraderie between us,” Farrar says. “They helped us get some really good guitar sounds and helped us flesh things out in terms of the finished recording being more than just doing what we normally did live. We were blown away when they brought in Rich Gilbert to play pedal steel on ‘Whiskey Bottle’ because that was an instrument that we hadn’t had the opportunity to record with before. He’s also playing that apocalyptic noise part at the end of ‘Factory Belt’ — just doing sweeps up and down the pedal steel with his slide.”

When it came time to package their newly recorded songs into a proper album, the band once again chose to wear its influences on its sleeve. Not only did they create a minimalist album cover aesthetic that mimicked releases from Moe Asch’s midcentury Folkways Records catalog, but they also titled the album No Depression after the traditional Depression-era folksong “No Depression in Heaven” that is often attributed to the legendary Carter Family. (While they were the first to record it, there is some speculation that A.P. Carter “found” the song more than “wrote” it himself). Uncle Tupelo had also recorded a cover of the song for the album, surprising many by foregoing the buzzier, bombastic side of their sound for a more true-to-form acoustic folk number. The folksy, back porch singalong vibe can also be found on No Depression tracks “Life Worth Livin’” and “Screen Door,” with Farrar adding mandolin to the former and Tweedy swapping out his bass for an acoustic guitar on the latter.

When asked where they got the idea to cover “No Depression,” both Farrar and Tweedy tell the same origin story and make the same point of clarification. Remembers Farrar, “I was digging through my mom’s record collection and found this old folk compilation that had ‘No Depression’ on it. I thought the song really resonated with the themes of Midwest isolation that we often explored, plus it passed the test with Jeff and Mike since it sounded like something Woody Guthrie would’ve done. Though, I should add this was the New Lost City Ramblers version.”

Tweedy gives a similar account, adding, “We really owe a debt to the first folk revival wave from the late ’50s, early ’60s. Years later, I actually got to thank John Cohen of the New Lost City Ramblers for that when we crossed paths at Newport for this Harry Smith anthology reissue benefit show that Wilco played.”

A Lingering Legacy

Since the release of No Depression, both Farrar and Tweedy have each built impressive catalogs of releases between their respective bands and solo albums. Both are also still extremely active in the scene they helped to shape; just last year, Son Volt released Union, Wilco released Ode to Joy, and Tweedy released his second solo album, Warmer. However, there’s a good chance that neither artist will ever fully outstep the larger shadow of what they created together on No Depression. This seems true for both their live shows — “‘Graveyard Shift’ is one that’s been requested a lot over the years,” says Farrar; while Tweedy admits “‘Screen Door’ still gets requested quite frequently when I play solo shows, and although I’m not a big fan of the song, I’m also pretty sanguine about the notion of something surviving that long” — as well as for how the album seems to be a template by which all of their other works are somehow measured in various ways.

It is that inescapability, that perma-pairing of their first artistic steps to every other musical statement they have made over the last 30 years, that seems to substantially shape the album’s complicated legacy, especially for its co-creators. This wasn’t always the case, however, as Tweedy remembers how some of the initial reactions to No Depression were quite polarizing: “Any reputation the album has now was certainly not present upon its release. I think that we felt almost like people were making fun of us sometimes. From my perspective, there were plenty of stinging rebukes by the cool kids. Like, Gerard Cosloy was the head of a label that put out a lot of records that we loved and then we heard he was making fun of us in CMJ. It was a long time before I felt like we had any kind of status or reputation whatsoever.”

In fact, that “long time” Tweedy references might’ve been the majority, if not entirety, of Uncle Tupelo’s run; as the band’s highest accolades and genre pioneering respects only started popping up in the wake of their breakup in May 1994. As Uncle Tupelo drummer Mike Heidorn told the Los Angeles Times in early 1996 (at the time, he was playing drums in Farrar’s new band, Son Volt), “Uncle Tupelo is bigger now than ever… I guess death is a great career move.” These days, Farrar expresses some of the same sentiments on that post-mortem timeline: “It must’ve started to some degree around late ’94 or so when we had this vague understanding of an online chat group that had been built around mutual fans of the band. Then, in ’95, when No Depression asked Son Volt to be the cover story for their first issue; that’s when it first started hitting home for me.”

Both Farrar and Tweedy acknowledge they haven’t sat with No Depression, the album, in quite some time, with the latter even stating, “It’s hard for me to really embrace the first record because I don’t think I had found my voice yet.” However, they both seem to take a mutual sense of pride in the hand-me-down musical ambassadorship inherent in their earliest work’s legacy. Reflects Tweedy, “In hindsight, it’s a thrilling thing to feel that you got to be a part of the actual tradition of sharing this particular knowledge with people that might not have come to it as quickly or maybe would have not even been introduced to it at all.”

In fact, Uncle Tupelo might’ve pulled off being one of the connection points between older musical traditions and modern-day audiences so masterfully that, at least according to Farrar, they may not have left many sonic fingerprints behind: “I don’t necessarily hear our own influence on other bands that much. Maybe it’s because everyone is kind of drawing from the same influences and it’s just kind of a continuum that goes on and on. Everyone’s heard The Replacements. Everyone’s listened to Dylan and The Byrds. Honestly, when I listen to this kind of music, the one person I definitely hear being most influential almost entirely across the board is Steve Earle. I think he gets the award, not us.” However, acquiescing a bit to their undeniable impact on the genre, Farrar later relents, “In terms of us being a reference point, I would just hope that we might be to another band what The Byrds were to us; an example of how to mix styles in order to go off in your own direction and make an individualistic stamp.”

It’s often an unfair expectation to want an influential artist to eloquently summarize their own impact on a broader pop cultural level. From their intimately interior vantage point, they might not be able to tell you what their groundbreaking work means to other people. But if we’re lucky, they can sometimes dig down deep enough to get to the heart of what it means to them individually. In the case of Uncle Tupelo’s No Depression turning 30 years old, Tweedy seems to get the most impassioned when thinking back on not what they were making at the time, but what they were learning — both about themselves and also about the world around them.

“I just remember this overwhelming feeling that Jay and I would talk about getting from listening to folk music and country music, and speaking for myself personally, it was like having the veil pulled back and realizing that the world has always been weird. The world has always been scary. So, when people choose to express themselves with music, it can also be completely untamed. It’s not always shaped by fashion or commercial viability or anything like that; people just want to express themselves with words and noise and sound. That’s what I think we were discovering in Uncle Tupelo. The revelation was: Once you have this knowledge, you can’t pretend that what anyone is doing is new. So why not embrace it?”