JOURNAL EXCERPT: A History of Yodeling in Roots Music

EDITOR’S NOTE: Below is an excerpt from a story in our Summer 2021 journal, “Voices.” You can read the whole story — and much more — in that issue, here. And please consider supporting No Depression with a subscription for more roots music journalism, in print and online, all year long.

As a child in Arkansas, Nick Shoulders’ young, cracking voice bounced off the rocky holler in his parents’ yard. It was there, against the backside of a mountain in the Ozarks, that he found ways to call out to friends nearby and practice yodeling.

“We came up with a whooping holler kind of thing,” says the 31-year-old, who has performed using the moniker Okay Crawdad. “We did it over and over again, and I realized how to get more projection out of using my diaphragm and belly. At a certain pitch, my voice would leap another octave up.” In those woods, Shoulders also practiced the related skills of whistling, bird calls, and mouth trumpet.

Most recently based in New Orleans, Shoulders has been spending the pandemic in Arkansas, where he readied his first solo release, Home on the Rage. Released under his own name and on his new label, Gar Hole Records, in April, the album features a full whistle track and quickly sold out of its first vinyl pressing.

Shoulders’ story of how he came to yodel, through landscape and lineage, is reflective of many who have found their voice and let it crack in the wind, off of mountains, and across plains.

What Makes a Yodel

The history of the yodel is surprisingly layered and weighted. Yodels arose around the world from the lungs of many, but it isn’t a part of every culture’s repertoire. As a kind of musical currency, it was spread through immigrant and slave ships, missionaries, airwaves, and on the backs of horses. The yodel found its most hospitable home in American popular roots music through many avenues and voices.

A yodel may evoke memories of “The Lonely Goatherd,” sung by Julie Andrews in the 1965 classic The Sound of Music, or Slim Whitman’s “Indian Love Call” that blew alien brains up in 1996’s Mars Attacks! But the yodel is a primitive call and its journey from the Stone Age to the big screen wasn’t a straight line.

Our emotional response to a yodel is “DNA-encoded,” according to yodel expert Bart Plantenga, author of YODEL-AY-EE-OOOO: The Secret History of Yodeling Around the World and Yodel in Hi-Fi: From Kitsch Folk to Contemporary Electronica.

The yodel started with a prelingual call, says Plantenga, who is based in Amsterdam. It eventually developed musical qualities and was next incorporated into wordless songs or a “pre-Gregorian scat.” It was then applied to a basic song structure, serving as a refrain. Eventually, the “yodel song” evolved into its own entity and later was commercialized through professional performances and recordings.

Although many people think of the yodel as “kind of like the heavy metal of the pre-electric period … intolerable and kitsch,” says Plantenga, he explains that they can also be soothing: “Cowboys, to calm the herds, if they were flustered by a thunderstorm or something, would yodel a lullaby.”

Despite some yodeling appearing in early American classical music, yodeling is a sound of the people, a folk sound, a working man’s sound. “While [the yodel] may seem omnipresent, it tends to find its most comfortable home in areas outside music’s mainstream, in hillbilly or in cowboy music, for example,” writes Timothy E. Wise, author of Yodeling and Meaning in American.

While many believe yodeling in American popular music is influenced only by Alpine yodels, Wise notes that the main influences come from Africa, Hawaii, and Europe. Plantenga agrees, adding that some Native American cultures also yodel.

Many early yodelers in North America were from Switzerland, Germany, and Austria. Swiss Mennonites and Anabaptists came to America starting in the late 17th century and set up colonies. The yodel helped give them their identity in this New World. German and Austrian yodelers arrived in greater numbers during the early 19th century. Around that time, these singers of European ancestry began touring the nation as Tyrolean yodeling groups with their complicated, undulating calls.

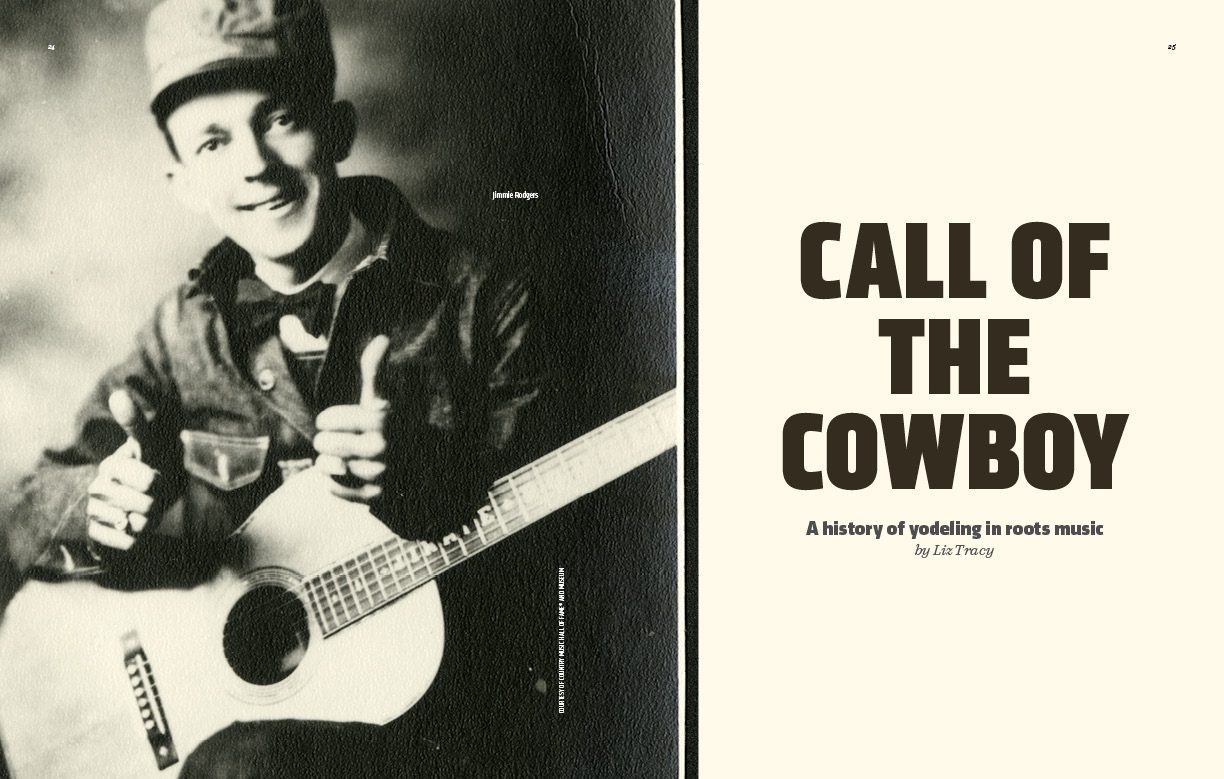

But in 1928, Jimmie Rodgers, “The Singing Brakeman,” brought the yodel to the mainstream in a new way with “Blue Yodel No. 1 (T for Texas).” Rodgers, probably the most influential country yodeler, learned to yodel while working on the railroads with Black Americans and borrowed from their work songs and blues music. His blue yodel songs have been interpreted by Dolly Parton, Bill Monroe, and many others.

In the 1930s, cowboy and Western-themed songs and hillbilly music were popularized through radio and film. Given that the yodel is used as a call to herds across lonely landscapes, the pastoral, solitary life of cowboys made them a prime conduit for the yodel. According to Wise, it became a cowboy signifier. “Yodeling found its contemporary habitat,” he writes.

Musicians like Hank Williams strengthened that cowboy image and tweaked the sound with his mid-word voice break. Plantenga wrote, “‘Lovesick Blues’ tore down the house and fans would faint when he yodeled — with audiences sometimes demanding 14 encores.”

The Yodel Endures

The biggest misconception of yodeling, according to Plantenga, “is that it’s dying,” but his second book aims to dispel this myth.

The yodel endures through the voices of singers like Jewel, Beck, the late Dolores O’Riordan of The Cranberries, and many others. Pop stars Justin Bieber and Benny Blanco revive it on their 2020 song “Lonely.” British roots singer-songwriter Yola belts out the occasional yodel, as does indie-folk artist Angel Olsen. Pharis and Jason Romero’s 2020 LP Bet on Love was nominated for Best Album by the International Folk Music Awards, and Pharis yodels beautifully on the title track. It’s also prevalent in the works of Roomful of Teeth, a Grammy award-winning ensemble of eight classically trained singers who use unusual vocal effects to perform commissioned compositions.

Scott H. Biram is an ordained minister, producer, and musician who has performed his signature yodel and songs in venues all over the globe, including Lincoln Center in New York City and the Roundhouse in London. The 47-year-old released Fever Dreams last November, is working on a new album, and is considering starting his own label.

When Biram was younger and playing with bluegrass bands, the yodel was their show-saver. “If the show was going to shit, I could yodel and impress everybody,” he says. It has continued to be a saving grace as he’s evolved musically. “As a one-man band, you have to have some gimmicks, some fireworks here and there.” Since he was the only one of his musical friends who yodeled, it also helped him stand out.

Biram started with a slow yodel so that his voice would break octaves. “No disrespect to Jimmie Rodgers, but that’s kind of the easier version of yodeling, it’s kind of slow, more straightforward yodeling,” he says. “To do the fast, rolling [yodel] where it sounds like there’s a turkey in your gullet takes some practice,” he admits.

“When you’re singing regularly, when you sing loud and proud and push from your abdomen, it’s kind of a release of some kind and relieves stress and makes you feel a little more like you have got some stuff off your chest. With yodeling it’s like that plus a little bit more. It’s very satisfying when you can pull it off. It feels really good.”