THE READING ROOM: Tracing the Drive-By Truckers’ Physical and Moral Map

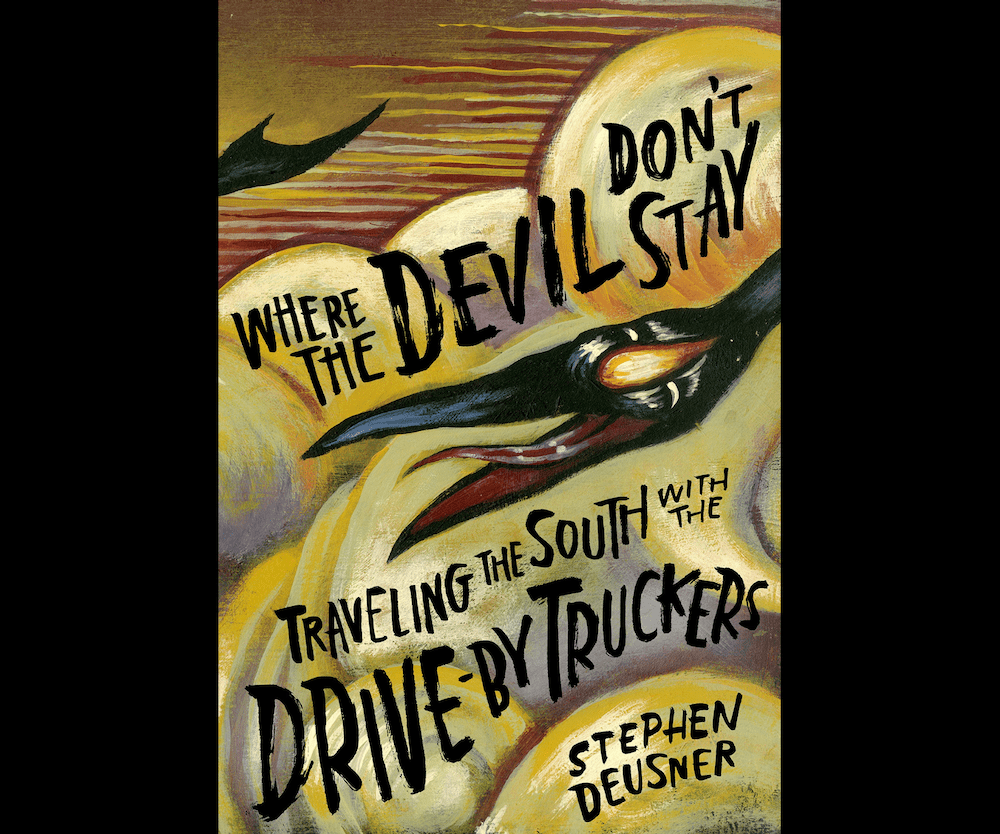

As music journalist Stephen Deusner points out in his captivating and insightful new book, Where the Devil Don’t Stay: Traveling the South with the Drive-By Truckers (Texas), “in crucial ways the Truckers have provided a rip-roaring soundtrack for a very personal reckoning with my own southern roots.” He continues: “In the following pages, I attempt to tell the band’s story in a roundabout way. It’s not a chronology, but a travelogue of sorts, a road trip through the southern wilds to visit the places the Truckers have been writing and singing about for more than twenty-five years now. More ambitiously, this book speaks to the power of music — the Truckers’ albums in particular and southern music in general — to do more than simply reflect a larger culture. Rather, music can frame and shape that culture, prompting us to question certain assumptions we make about ourselves and other people, whether we’re listening on headphones in our rooms or with other people at a bar in downtown Birmingham.”

Drawing on interviews with all the members of the band, Deusner follows the Truckers as they evolve from their origins in 1996 to their current lineup and the ways that they deal with the tangled cultural landscape of the South out of which they arise. Nodding to the power of place in defining identity, Deusner arranges the book not chronologically but by tracing the band through the cities and places that have shaped their musical identity. Deusner’s book is essential reading not only for fans of the Truckers but for anyone wanting to discover more about these quintessential roots rockers.

I chatted with Stephen Deusner recently about the book and the writing of it.

What prompted you to write this book now?

It’s something that I’d been wanting to tackle for a long time. When I first heard the band I thought, “This is a band doing something really different,” and my experience with them was so intense I thought, “I want to write a book about this.” That maybe was around the Decoration Day, Dirty South era, and obviously the time was not right. I wanted to see where they went, so I just kind of kept it in the back of my mind, and I covered them a lot going forward. I was talking with David Menconi, who was the co-editor of the American Music Series [at University of Texas Press] at the time, and we kind of hashed out the idea of a book about the band — he was very involved. But it really took moving to England for a while. My wife got a really good fellowship in Birmingham, and we kind of lived off in this weird lodge at the edge of campus and there was this really bad student neighborhood right next to it. So there was nothing to do there. Then there was this great neighborhood on the far side of the campus. So I had to walk a mile or mile and a half to get to a really good coffee shop and work. That gives you a lot of time to listen to music and to reflect on where you are and on the newness of your surroundings. Listening to the Truckers at that time gave me this new perspective on them and on my home as well, and I just remember thinking that every song is about a place. That stuck out to me, and the more I thought about it, the more I thought that instead of following a time line you could follow a map in their music, So that’s when this really started to gel for me, this idea that you didn’t have to tell their story chronologically.

Did you come to like the band more, or less, as you were writing the book?

I would have to say more. I was surprised by that. I kept thinking there’s going to be a point where I get sick of this band. And I never did. It’s amazing. I just remember all through the process, even during the worst down time, when I was really afraid I couldn’t do it, or when I was just wracked with self-doubt and having a hard time managing it, I would just go back to their music and just be completely inspired again and it never got old. Even now I go back to their stuff — like I’ve heard “Zip City” a thousand times by now and it still excites me — and I would say I like them a lot more now but I’m also sort of surprised by that. I think that speaks well of them and of the complexity and of the passion of their music.

Where does the band lie in the Southern musical landscape, somewhere between Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Athens scene? Where in that lineage do they come in your mind?

That’s a good question, and it’s one I’m still kind of wrestling with. When they did sort of arrive with Southern Rock Opera, they were a Southern band and they were consciously embracing Southern rock band as an identity even as they were redefining what that meant — taking certain things and pushing against certain things. The complexity in the songwriting of Lynyrd Skynyrd, where it’s coming from a very specific point of view and it’s not just kind of this larger cultural project where you sort of want to be the voice of this demographic; it’s a very personal perspective that’s coming through with a lot of contradictions, and I think that’s one thing that they liked. They did not like, for instance, the Confederate flag. I think they were defining themselves even as they were sort of almost redefining what Southern rock means. But then again they are a band from the Shoals, so they embody a lot of that; I mean, it’s an inheritance: David Hood is Patterson’s dad. Then going to Athens: Even if they don’t sound like the Elephant 6 band, there’s a lot of that spirit, I think, in what they’re doing. One thing I’ve realized is that they have been so many different bands along the way. They were an all-country band, a Southern rock band; in 2016 they redefined themselves as an American band. They’ve just had so many different identities; they have such a sprawling catalog that it does kind of make it hard to pinpoint where they fit because they fit in so many different places.

In the book you observe, “The Truckers don’t ignore the South’s history of racial inequality and violence in their songs, but they’ve learned to be observers, to ask questions and let others provide the answers.” Do you think this continues to describe the band?

I think it is changing a bit. I think they’re very careful. At least that’s how it comes through in their songs. Like they’re not trying to speak for a Black experience or anything other than just a white male experience that is very concerned about what’s going on and trying to do the right thing. Even “Watching the Orange Cloud,” that’s a song about observing, about seeing all of this stuff going on around you and trying to figure out what to do. “What It Means” is a song that is literally about asking questions that maybe you don’t know the answers to right away and the importance of having questions that don’t have immediate answers. So, I think those two kind of speak to that idea that the band are watching and they’re documenting and they’re observing and they’ve got their own set of virtues and ideas and morals, but it’s not a fixed thing. They’re always evolving as people and as a band. Just like everybody else is kind of figuring these things out over time.

What did the book teach you about yourself? This is your story, too, in some ways.

I’m from Selmer, Tennessee, about 90 miles east of Memphis, not too far from where they’re from, but I spent a good part of my childhood in Birmingham, Alabama. I think, especially being of a certain generation, when I went to school I took classes in Southern literature and Southern history and those were pretty broad, but I always got the sense that there was one South and I was the main character, as a white guy. There are all these other things happening but they were the supporting characters, so to speak. I think going through this process made me realize that’s not the case. There are so many different Souths; everybody is a main character. There’s so much happening that my experience is only representative of my experience. Learning about all these things — such as Southern hip-hop and the Geechee Gullah cultures on the East Coast — made me realize that the South as I’ve experienced it, I always thought was The South, but it’s not; it’s just A South. Rather than feel threatened by that, I feel like that’s really amazing and beautiful, like we’ve got this whole multifaceted region and culture that I want to explore more of, and no matter how deep I dig there’ll still be more to come. That to me is inspiring.

What do you want readers to take from the book?

I want them to take away that this is not an endpoint, this is not the culmination of something. It’s more like a step along the way in processing all of this, in figuring out what this means. It’s more like the start of something than the finish of something. It was for me, and I hope it will be for people, that it will be thought-provoking, maybe give them some different angles on some of these issues. More than that, though, I just want ’em to listen to the Drive-By Truckers. I just hope this sends so many listeners their way, and I hope people crank it up as loud as they can and then crank it up a little louder.