THE READING ROOM: Doobie Brothers Memoir Is Just Alright

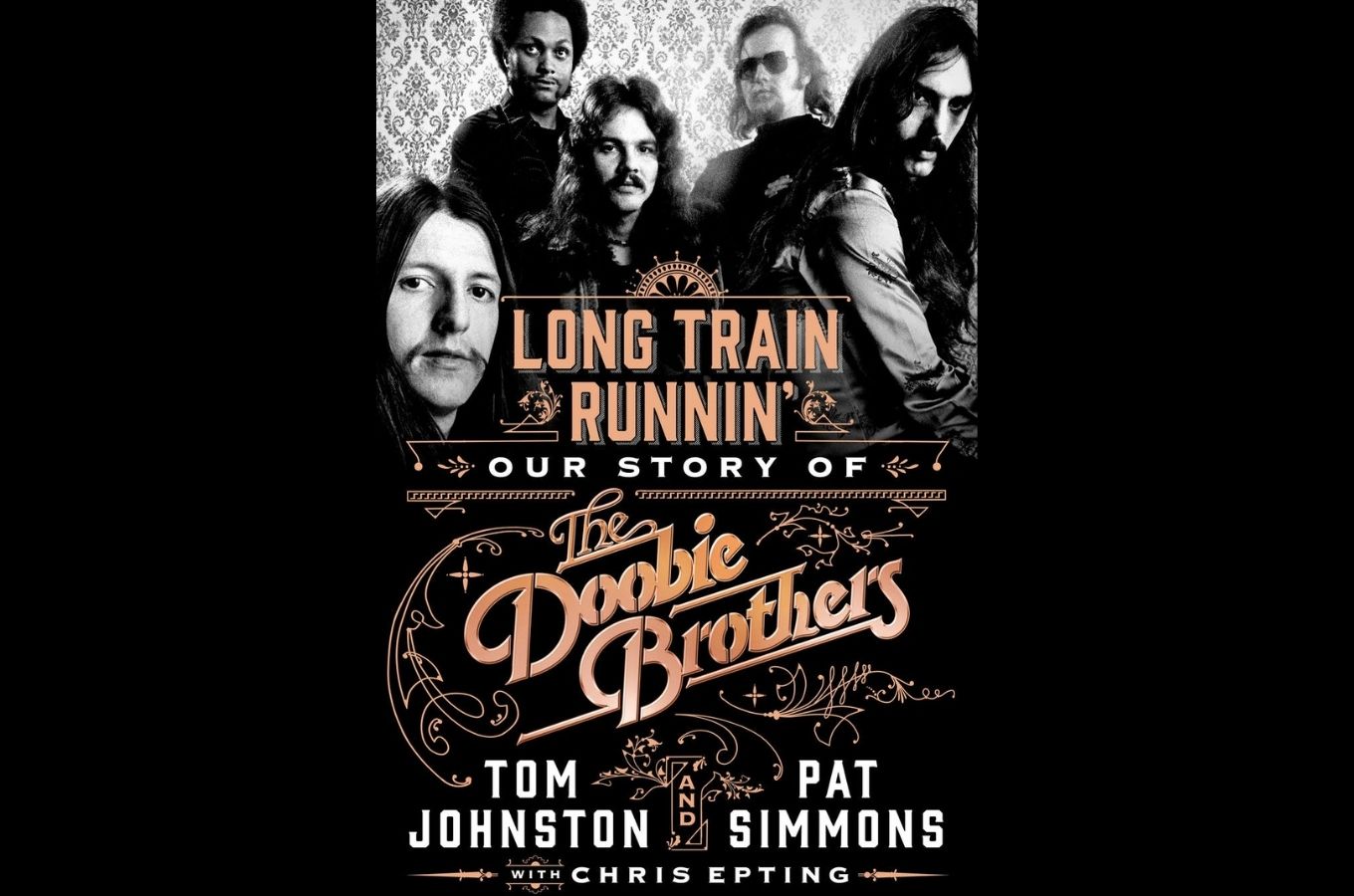

Old rockers never die, nor do they fade away; they write their memoirs. Or, in the case of Long Train Runnin’: Our Story of The Doobie Brothers (St. Martin’s), band founders Tom Johnston and Pat Simmons tell their stories to writer Chris Epting to produce an oral history. It’s an effort to reconstruct 50 years of running down the road from song to song, gig to gig.

The virtue of an oral history, of course, is that we get to listen to these guys tell their own stories in their own words, to share their memories of wasted days and wasted nights, to maunder over the collections of instruments and gear they used in making their music, and to reflect on the nature of music and songwriting. The shortcoming of an oral history, though, is that the stories flatten out, growing tiresome and appealing mainly to fans.

The crunchy opening guitar riff of The Doobie Brothers’ “Long Train Runnin’” and the bright, jangly chords of “Listen to the Music” continue to reverberate through the smoky bordellos and dance halls of rock and roll. These riffs are instantly recognizable and fill the dance floor when a cover band cranks them out or when a DJ spins the songs. Apart from a couple of other songs — “China Grove” and “Jesus Is Just Alright With Me” (written by gospel singer Art Reynolds and recorded in 1966 by the Art Reynolds Singers, but made most famous by The Byrds in 1969) — The Doobie Brothers are one of those bands that got lost in the shuffle of like-sounding bands in the early to mid-1970s. The band formed in 1970 in San Jose, and they gelled in the shows they played at Chateau Liberté, a “bohemian/biker hangout” in the Santa Cruz mountains. The core of the band formed when Moby Grape’s Skip Spence introduced drummer John Hartman to guitarist Johnston. In 1970, guitarist Simmons and bassist Dave Shogren joined them and they called themselves The Doobie Brothers. As Simmons recalls of the way the band got its name: “Evidently, some of the guys were sitting around the breakfast table one morning, sprinkling pot on their cornflakes, smokin’ joints, and bein’ crazy. I wasn’t actually there. At that time, whenever anybody said, ‘I wanna smoke a joint,’ they said ‘Let’s smoke a doobie.’ So someone in the room says, ‘Hey, you guys smoke so many joints, why don’t you call yourselves the Doobie Brothers?’” Both Johnston and Simmons recall thinking it was a dumb name, but once they let the music do the talking, the name became synonymous with their sound.

The Doobie Brothers’ fame rose like smoke wafting off, well, a doobie from that first gig at the Chateau in 1970. They were signed to Warner Bros. and released their first, eponymous album in 1971. Their second album, Toulouse Street, came out a year later, and the singles “Listen to the Music” and “Jesus Is Just Alright With Me” sent the band soaring. One year later, The Doobie Brothers released The Captain and Me, an album that secured their presence in the rock pantheon with “Long Train Runnin’” and “China Grove.” By 1975, the band’s quicksilver rise to fame stopped short when Johnston had to retire because of a bleeding stomach ulcer. Pedal steel guitarist Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, who joined the band in 1974 from Steely Dan, suggested Michael McDonald, who had sung backup vocals in Steely Dan, to Simmons as a successor to Johnston. McDonald became the lead vocalist of The Doobie Brothers from 1975 to 1982, taking the sound of the band from the hard-driving blues rock of the early albums to a soul jazz pop sound.

In 27 chapters, arranged in roughly chronological fashion and mostly named after Doobie Brothers songs, Johnston and Simmons retrace much of this history, as well as their own journeys as musicians. Growing up in a small central California town, Johnston recalls that “I was a rebel in waiting.” He started playing guitar at age 12, and by the time he was in college he had a blues band of his own and was also playing in a soul and wedding band called Charades. Johnston cut his musical teeth on B.B. King, Albert King, and Freddie King, and James Brown.

Simmons grew up in Washington state, but he and his family moved to California. Although he started taking piano lessons, he quit not long after he moved to California; around the time he was 8, he picked up guitar and eventually started taking lessons from a guitar teacher named Annette, who introduced him to Joan Baez and Mississippi John Hurt, among others.

“These artists were different than Bob Dylan, but they still had a lot to say,” Simmons recalls. “I loved folk music and obscure Appalachian songs. I absorbed all of that incredible American music as a teenager and decided that’s what I really wanted to play.”

Johnston and Simmons met in San Jose through Skip Spence, the former guitarist for Moby Grape, with whom Johnston and John Hartman were playing at the time. As Simmons recalls: “Tom was really good. Great guitar player, great singer. I was very impressed. Tom had an original style, distinctive voice, and interesting songs … I spoke with them [Johnston and Hartman] after they were done, and they asked me if I would be interested in this other band they were thinking of putting together with two or three guitarists and a lot of vocals.” Johnston recalls of that meeting: “I was really impressed with Pat’s playing. It was the first time I’d really watched somebody who had fingerpicking down cold. He was into a very different style than what I was used to, which made his playing that much more interesting and somewhat exotic … He was so connected to so many purely American musical forms from folk to blues.” The rest is music history.

Even the best music memoirs float like gossamer threads through the air, wrapping us momentarily in glittering webs but snapping crisply and sailing away forever. They’re ephemeral, lining the clogged gutters of our cultural history. They eventually wash away, but it’s the songs that survive. “South City Midnight Lady” and “China Grove” and “Natural Thing” endure more than this memoir will, so take the Doobies’ advice and “Listen to the Music.”