JOURNAL EXCERPT: The Weird and Wonderful World of Wes Freed

EDITOR’S NOTE: The team at No Depression is saddened to hear about the passing of visual artist and musician Wes Freed. His work graced almost every Drive-by Truckers album cover, as well as gig posters for bands like American Aquarium, and even regular ND contributor and author Stephen Deusner‘s book about the Truckers. Their tributes are linked, and in Freed’s honor, we’re sharing this excerpt of a story about his book and his art from our Winter 2019 journal, “Vision.”

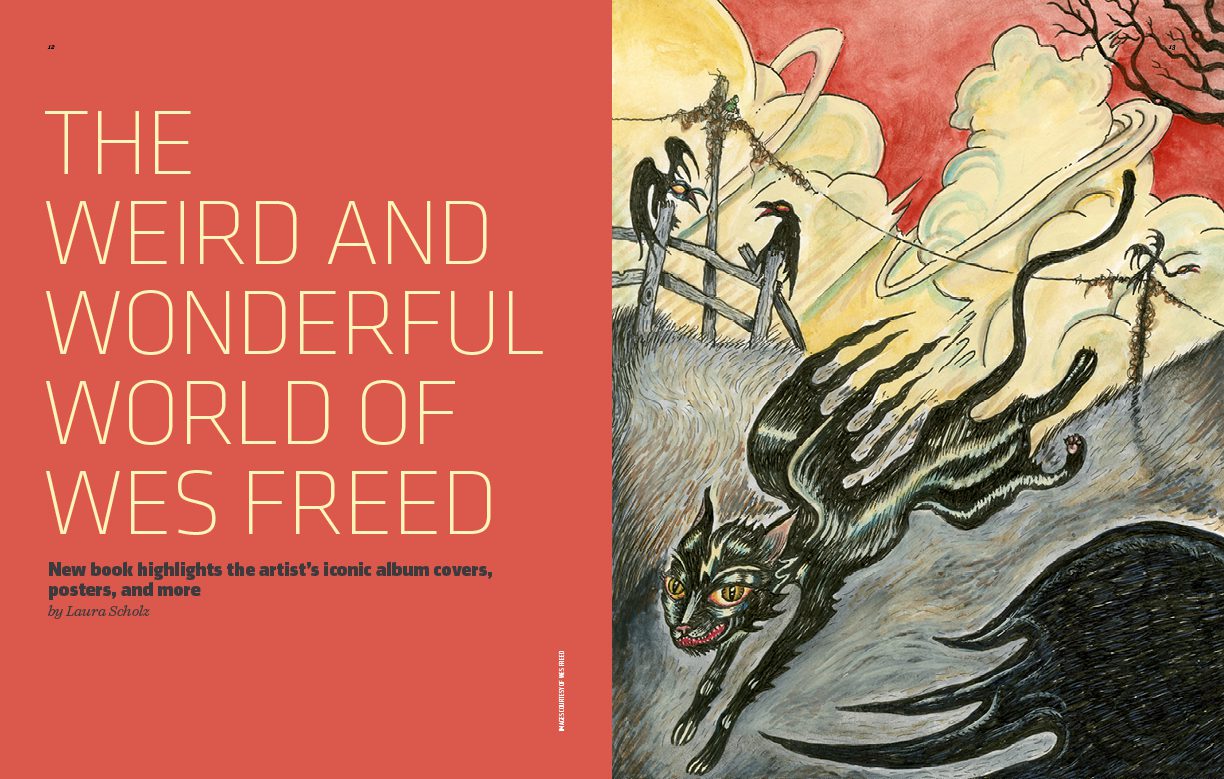

Growing up on a farm in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley in the shadow of Civil War battlefields, Wes Freed’s fascination with the macabre began at an early age. Using drawing paper and other supplies he pilfered from school, the artist spent his childhood doodling battle scenes, spooky rural landscapes, skeletons, and other images that would come to shape his signature Southern gothic style.

Freed sold his first piece of art — a portrait of either Gene Simmons or Peter Criss, he couldn’t remember — in high school, about the same time he joined his first band, two acts that cemented his destiny as an artist with serious rock and roll roots.

While that high school print didn’t quite make the cut, more than two decades of Freed’s other work has been commemorated in the 2019 coffee table-style art book, The Art of Wes Freed: Paintings, Posters, Pin-ups and Possums. Featuring a foreword from Drive-by Truckers co-founder and longtime collaborator Patterson Hood, the 160-page anthology of Freed’s art includes his iconic album covers for the Truckers, portraits of music legends like Hank Williams, concert bills, his Willard’s Garage comic strip series, and more.

The Richmond Scene

When not doodling Civil War soldiers or painting moody landscapes, young Freed spent his formative years surrounded by music.

“No one in my family played music that much, but we played a lot of records,” he said. “This was 1975 and 1976, so we were listening to folk musicians like John Denver and Gordon Lightfoot, plus lots of outlaw country from Waylon and Willie,” he continued, citing the latter as foundational musical influences.

By the time he attended high school in the early 1980s, his tastes had turned to punk rock. He spent hours listening to The Clash and The Stranglers and, in spite of not playing an instrument, was determined to join a band.

“Luckily, this guy who lived down the road from me, David Powers, played guitar, and he taught me how to play, and let me sing a little,” Freed recalled. Later, Freed, Powers, Powers’ brother Danny, and C.J Botkin formed a band called The Victims.

Freed joked his first official “recording” with that band was a cover of The Rolling Stones’ “Emotional Rescue,” made using “parts and pieces of Frankensteined cassette players.”

Freed eventually learned to play the fiddle and attended art school at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, studying painting and printmaking and immersing himself in the fantastical works of Hieronymus Bosch, Francisco Goya, and Edward Gorey as well as the city’s emerging music scene.

“Everyone in Richmond at that time was a musician or artist or both,” said Freed, who thrived in the hyper-creative community. He stayed in the city after he graduated, playing with a string of bands ranging from the metal-influenced Mutant Drones to the country-tinged Mudd Helmet — which eventually morphed into Dirtball — and continued to pursue his art while painting houses to pay the bills.

In 1991, a local independent paper commissioned him to create a comic strip series, and the famed Willard’s Garage world was born. Using a garage he passed every day growing up for inspiration, he developed elaborate backstories for his characters, whom he envisioned as mechanics and moonshiners, thus creating the framework of what grew to be his definitive style — eerie pastorals, an otherworld inhabited by skeletons, barren landscapes, looming bats and crows. It was dark, but always with a hint of humor and whimsy.

It was these artistic qualities that captured the attention of other local musicians, notably upcoming singer-songwriter Lauren Hoffman and David Lowery and Johnny Hickman of the alt-rock band Cracker in the mid-to-late 1990s.

Hoffman, drawn to Freed’s art because of its combination of “spookiness” with a “traditional Southern folk element,” commissioned the artist to design the cover of her 1997 LP The Chemist Said It Would Be Alright But I’ve Never Been the Same, which Hickman and Lowery produced.

“I love the way Wes creates these totally signature characters and creatures and places them in his spooky, wonderful rural landscapes,” says Hickman, who along with Lowery commissioned Freed to design the cover for what would become the band’s 1998 album, Gentleman’s Blues. With stark trees, moody moonscapes, and a winged black cat that has become such a calling card for the band that several fans have gotten tattoos of it, the artwork is signature Freed.

Drive-by Truckers Days

Freed’s art might have stayed a local phenomenon if not for a chance meeting with The Drive-by Truckers at Bubbapalooza, an annual roots music festival at the storied Star Community Bar in Atlanta in 1997.

As Freed recalled, he was impressed by the band’s music and wanted to introduce himself, but was a bit hungover and “couldn’t muster up the gumption” to approach them. So his then-wife and bandmate Jyl did, inviting the Truckers to attend one of the couple’s monthly Capital City Barndance gatherings, an event Freed describes as “Hee-Haw meets The Grand Ole Opry” and “alt-country with a punk rock attitude.”

The band crashed with the Freeds, and, as Hood recalls it, walking into the Freeds’ home that fall was like walking straight into one of Wes’ paintings, with foster animals, overgrown grass in the yard, and his overworldly paintings covering every surface of the home’s interior.

“It was kind of like a miniature haunted house, like the Boo Radley house in To Kill a Mockingbird, where kids in the neighborhood walk to the other side of the street,” he says.

Hood and Mike Cooley were immediately taken with the Freeds’ aesthetic, which Hood describes like this: “Its own universe — old-timey, but timely, incorporating what’s current into what’s old.” The band tapped Freed to collaborate with them on their ambitious Southern Rock Opera project, a double LP the band released in 2001. Back before the era of digital files, the band would send Freed rough mixes of tapes as they worked on the record, which Freed would then listen to as he sketched and developed thematic ideas for the cover.

The result was the now-iconic, large-winged bat flying over mythic and desolate Highway 72. Freed worked diligently with Hood’s sister, Lilia, a digital graphic designer, to develop the complete album package.

“She vowed early on to be true to his work and never alter it, which cemented his trust. We’ve been working with him ever since,” says Hood of the partnership.

That fateful collaboration launched a decades-long relationship and resulted in other notable covers like 2003’s Decoration Day, with its massive cranes looming large over a graveyard, and 2011’s Go-Go Boots, with the namesake boots in siren red in the foreground.

Freed’s personal favorite, however, was 2004’s The Dirty South, which was an entire painting turned into a foldover sleeve for the album cover. In addition to the crane and the tornado — which he and Hood agreed were central to the record’s themes — Freed wanted to illustrate this line — “my Daddy played poker on a stump in the woods back when the world was gray” — from “Where the Devil Don’t Stay,” which led to cover’s central image.

Art, Music, and Legacy

In addition to designing albums, posters, and concert flyers for the Truckers, Freed also created from watercolors, builds custom frames, and accepts commissioned projects. An animal lover and proud owner of Betsy, a Schnauzer rescue, and Ella, a West Highland terrier, he found a niche painting pet and even family portraits.

“I do them in my own weird-ass way, but the people who get it, get it,” he remarked, noting he’s often too busy to work on “the stuff that comes right out of my head, because it doesn’t pay the bills.”

While Freed had a solo art show at the Jacksonville Center for the Arts in Floyd, Virginia, in 2015, this book was the first time his life’s work has been featured in print.

When asked if he considers himself more a writer or an artist, Freed responded, “I spend a lot more time making paintings than I do writing or playing music, but I don’t really separate the two in my mind. When I write songs they are like word paintings, and my paintings, to me anyway, are kind of like songs. Not even two sides of the same coin so much as the coin being melted down so both sides are intermingled.”