THE READING ROOM: Chicago’s Central Role in Shaping Roots Music

Describing Chicago, Saul Bellow once wrote, “Provinciality is not altogether a curse, we gain from our backwardness.” Chicago wears the mantle of the Second City, taking a back seat to New York in almost every category including theater, cuisine, and music. Chicagoans see the phrase as a tongue-in-cheek description, often stressing that Chicago’s music scene or theater scene shines more vibrantly than New York’s scenes (or LA’s or Nashville’s). As Bellow points out, though, being provincial has its promises, and there’s a freedom in such locations that can’t be found in larger, less provincial cities.

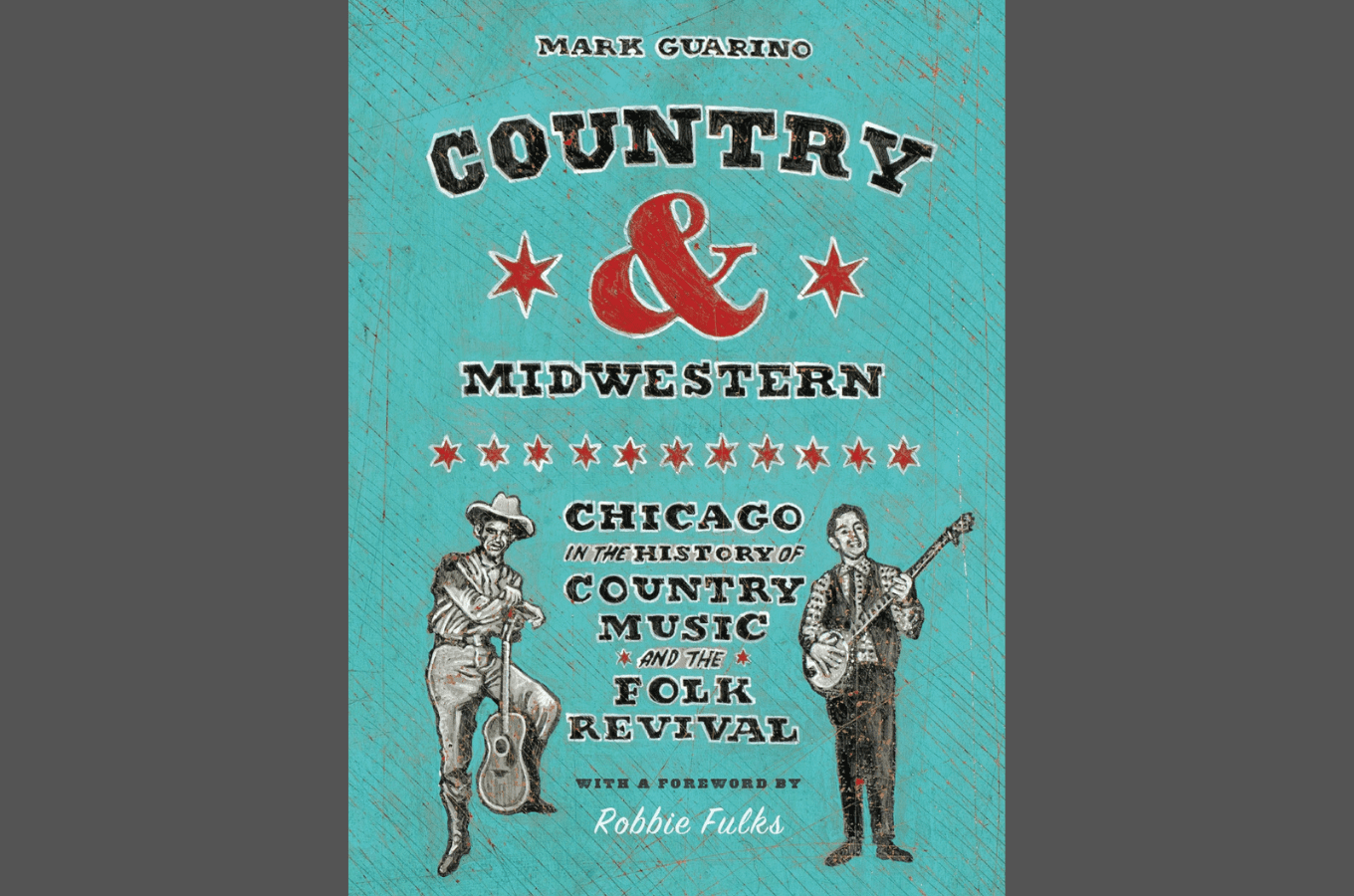

In his monumental new book Country & Midwestern: Chicago in the History of Country Music and the Folk Revival, music writer Mark Guarino tells a riveting story of the central role that Chicago has played in the development of country and folk music. Every chapter of the book features stories of people (like Patsy Montana, Lily May Bedford, The Coon Creek Girls, Ella Jenkins, Steve Goodman, Jeff Tweedy), places (the Gate of Horn, the Quiet Knight, the Old Town of Folk Music), and events (the WLS Barn Dance, the National Folk Festival) that have made Chicago home to a growing and vibrant music scene.

Before the Grand Ole Opry became a staple of WSM in Nashville, WLS (which stood for “World’s Largest Store,” a nod to station owner Sears, Roebuck, and Co., based in Chicago) first put the Barn Dance on its airwaves on April 19, 1924. The station director, Edgar L. Bill, looked for “‘old-time fiddling, banjo and guitar music and cowboy songs,’ the kind of entertainment that he felt a farm audience would appreciate, just as they appreciated the agricultural news and market reports broadcast throughout the week,” Guarino writes. Bill’s hunch paid off —the show was a success. George Hay, who would eventually move to WSM, played a pivotal role at the station, injecting “folksy humor into the Barn Dance that would continue long after his exit,” Guarino writes.

The Barn Dance grew in audience and stature, drawing musicians from rural areas in the South and Midwest to Chicago and launching their careers, but it had waned and finally went dark by the end of the 1930s. As Guarino points out, “Even though the Barn Dance had served as the prewar incubator for what would become the country music industry, by its end Chicago was establishing itself as a global headquarters for professional services … regionalism took over, and the sound, themes, and down-home culture of country music started to sound more comfortable nestled in the South than in the sleek skyscraper canyons of Chicago.”

Guarino observes, though, that country music never left Chicago completely, continuing to thrive in the hillbilly bars and dives of Uptown. But by the 1960s, the music scene in Chicago reinvented itself once again with the city’s folk revival. Before there was a club or coffeehouse scene in Chicago, Pat Philips, “a young woman just a year out of Northwestern University,” decided to become a concert promoter because at the time “the music she was drawn to did not have a respectable home.” Eventually, Philips joined “an underground circle of radical thinkers, left-leaning college students … at their gathering place, the College of Complexes, … Folk music found a home at the College before a club scene for it existed.”

Guarino explains, “a catalyst for folk music’s development in Chicago was ‘I Come for to Sing,’ a successful and long-running folk revue featuring Big Bill Broonzy, actor and radio host Studs Terkel, folk singer Win Stracke, and tenor Larry Lane. The revue presented traditional folk and blues songs and Elizabethan ballads … it marked the first significant event in the postwar era of Chicago folk music.” Folk music clubs soon stared to appear, chiefly the Gate of Horn, run initially by Albert Grossman, who would manage Peter, Paul, and Mary and Bob Dylan, among others. Stracke, with Dawn Greening and Frank Hamilton, opened the Old Town School of Folk Music in 1957, offering a blueprint for future classes: “The method of instruction …was designed to produce music for the sake of personal enjoyment as opposed to shaping future stars,” Guarino notes.

Guarino’s rich history moves from the early folk revival up through “Chicago’s second folk boom” — out of which emerged John Prine and Steve Goodman, among others — and the “insurgent country” of Jeff Tweedy and Wilco, the Sundowners, The Waco Brothers, and Robbie Fulks. As Guarino points out, the Old Town School stands as a fitting image for the enduring, and still developing, legacy of country and folk music in Chicago. When the Old Town School opened in its new location in 1997, with an expansion in 2006, it embodied “Win Stracke’s vision: his imagined utopia where ordinary people met outside the demands of their lives’ routines to make music together, in one spot, for no reason but to strengthen a connection otherwise unattainable amid the noise from the other side of the door. The longevity of the Old Town School … made it a vehicle for country and folk music in Chicago as the music grew and transformed over decades and through generations.”

Country & Midwestern: Chicago in the History of Country Music and the Folk Revival is essential reading for anyone interested in the history of country and folk music, and to learn more about the book’s creation and the story it tells, I chatted with Mark Guarino recently:

What prompted you to write the book? How long did it take you to write it?

The book took about 10 years, but I had the idea almost 20 years ago but just didn’t act on it right away. I’d grown up under the umbrella of Baby Boomer nostalgia. I missed out on all these music scenes — New York punk, the psychedelic ’60s — and wanted to be part of a scene like that. As a full-time music writer in Chicago in the 1990s and early 2000s, I realized that I was watching such a scene happen. I watched all these artists who then were just getting started grow and develop and get bigger and bigger. I started thinking back to the history of folk and country music in Chicago. Every chapter was an act of discovery for me; every chapter really could have been its own book. I hope it serves as a foundational book that others can use in the writing of music histories.

Why Chicago? What was special about Chicago?

Early on, it was the biggest city in the central part of the country. Southerners moved here because there was a lack of opportunity in the South; there were more jobs here. There was also a freedom to create in Chicago. Artists around here lived comfortable lives and didn’t have the industry looking over their shoulders. In addition, Chicago was a recording center: Many people don’t realize that Bill Monroe recorded most of his seminal albums in a studio on Michigan Avenue. Even today, Chicago is collaborative city. There’s a core of really great musicians helping out musicians just getting started in the scene.

What surprised you in your research or in your writing?

Really that there was so much more activity than I realized. The number of Southerners here was greater than I realized. On the north side of Chicago, people had twangs living in Uptown (chuckles). Chicago had the first all-country station, WJJD, outside of the South. There were also some themes that emerged as I was writing. One was that the city of Chicago did a really effective job of trying to shut down bars and clubs. The city of Chicago has never been kind to small business owners or owners of bars; that’s a trend that continues today. Another was the theme of reinvention. Starting with the Barn Dance, artists had the freedom to reinvent themselves and to reinvent music through the years. Bonnie Koloc incorporated jazz, for example, in her folk. John Prine had this Midwestern minimalist humor in his music. Alt-country combined these classic themes of country music with instruments that modernized the sound. Yet another theme is that the musicians here are not chasing commercial success, even though it might arrive, and that’s very influential for what’s going on here.

Win Stracke plays a key role in the book. Can you talk more about him?

Stracke shows up in a number of chapters from the start of the book. He appeared on the Barn Dance, and then he was active in the labor movement with Studs Terkel and Big Bill Broonzy and singing labor songs. He was a classical singer, and he was well known from his TV work. At the same time, though, the FBI and others were investigating him for what they thought were his ties to the communist party. He helped create the Old Town School of Folk Music. With Old Town School, he created an institution that had the values of early folk music: it’s not about the performer, it’s about the song. People moved from all over the country to take classes at Old Town School of Folk Music. It helped keep this music alive.

What would you like readers to take from the book?

Chicago needs to enter the conversation whenever we talk about country music and early American music. The book pulls all this information about the development of country and folk music in Chicago in a cohesive way. I hope readers will see the role the city and musicians in the city have played, and continue to play, in the development of country, folk, and roots music. There is an innovative culture here that encourages experimentation and invention.

Country & Midwestern: Chicago in the History of Country Music and the Folk Revival by Mark Guarino was published May 9 by The University of Chicago Press.