THE READING ROOM: How Does It Feel? Bob Dylan’s Bandmates Share Stories

Ever since he took that first ride down Highway 61, Bob Dylan has had hellhounds — well, biographers and critics — on his trail. The countless volumes devoted to Dylan look under every stone for clues to the meanings of his lyrics or for signs that will uncover some magical formula lying beneath Dylan’s enigmatic presence. Literary critics have joined the revelry, casting Dylan as a poet and plumbing his lyrics as they would a poem by Milton, Keats, or T.S. Eliot. In short, every new biography or critical study works a different angle of Dylan’s life or songwriting or performing. Fans seem never to tire of seeking out new facets of the Bard whose silence and inscrutability are the other side of his sly grin.

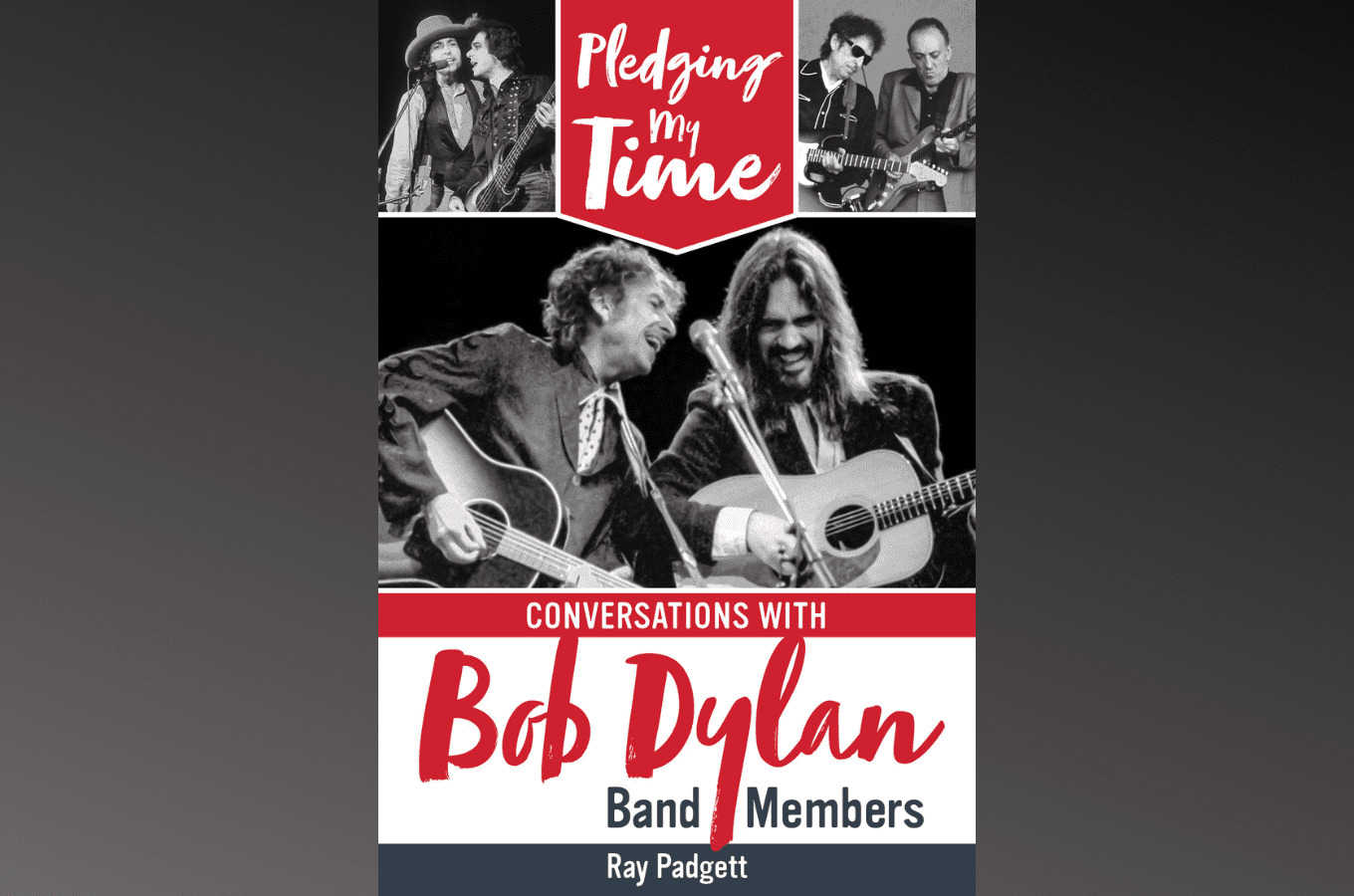

What’s it like, though, to stand on the stage with Dylan, to play or sing with him, to tour with him? In his new book, Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members, Ray Padgett collects interviews with over 40 artists and others who’ve worked with Dylan. As Padgett remarks, these sidemen and sidewomen are the only ones who can answer questions such as (paraphrasing a Dylan song): “How does it feel … to stand onstage next to Dylan and realize he’s just launched into a song you’ve never rehearsed?” “How does it feel … to spend months on end riding buses and planes with Bob Dylan from town to town?” “How does it feel … to be expected to keep those songs fresh every night, with little explicit direction from the boss?” As Padgett points out, Dylan has made it clear over the years that “his heart is first and foremost in live performance, so the musicians with the closest access to Dylan’s creative force are those that have logged miles with him on the road.”

Padgett arranges the interviews in roughly chronological order, running from Dylan’s days in Greenwich Village in the early ’60s — interviews with Noel Paul Stookey, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Happy Traum, for example — up to his 2020 album Rough and Rowdy Ways, addressed in an interview with Benmont Tench. Readers can dip into the interviews with artists who interest them the most, or they can read from first interview to last. As with any book of interviews, there is some overlap and repetition, but each interviewee offers a singular enough perspective that the repetition is not bothersome.

Padgett includes interviews with people who did not share the stage with Dylan but who came to know him by booking him and creating spaces for him. Betsy Siggins, for example, who was a founder of iconic Cambridge, Massachusetts, folk club Club 47, first meets Dylan at her club and later at the Newport Folk Festival. She recalls her impressions of Dylan in ’63 and ’64: “He was a magnet. When he performed with Joan [Baez] in workshops, those were stunning performances. … People were curious about his ability to write prolifically. … In those days the artists stayed at the Viking Hotel, a very famous hotel in Newport. I was there one night for a performance in the bedroom with Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan. That wasn’t planned. They just ended up in a room together. There were maybe 10 or 15 of us in that room. The two of them were so nervous.” At a later time, she remembers “going to Rick Danko’s house once and staying there all night long. Everybody was drinking and smoking and carrying on. At some point, somebody said, ‘The sun’s coming up. Let’s go outside.’ We all traipsed outside as the sun was coming up to sing ‘Amazing Grace’ lying in the snow. That was a beautiful, beautiful memory.”

Regina McCrary of The McCrary Sisters sang with Dylan for three years, from 1979 to 1981, during his “born again” period. She recalls getting a call from a friend asking if she wanted to audition for Dylan: “I did not know who Bob Dylan was if he was standing next to me on the bus stop. Other than a few songs, I never knew who he was.” When she showed up for the audition, she sang three songs: “Everything Must Change,” “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” and “Amazing Grace.” “The first song I don’t think moved him,” McCrary says. “The second song made him look, and the third song he jumped up and said, ‘That’s what I want.’” McCrary also reveals her method for keeping up with Dylan on stage: “Bob really never did the same song the same way all the time. There were times that he walked up on stage and you could tell that he was feeling and thinking different. I learned to watch his mouth and watch his feet. That helped me as far as if he changed the phrasing of how he did a song, or he wanted a beat to change, or to slow down or speed up, or to put another feel on it. You would watch him, and you could just kick right in.”

Violinist Scarlet Rivera, whose mystical and glowing presence lit up the stage on the Rolling Thunder Revue, talks about her first meeting with Dylan and what she tried to contribute to his music. Dylan discovers Rivera walking down the street: “I was walking down 13th street off of 1st Ave,” she recalls. “He pulled over and asked, ‘Can you play that thing?’” Our conversation was short and sweet. Perhaps it knocked him off of his feet, because he said he had to hear me play.” Rivera goes to Dylan’s loft and plays for an hour or so, and then he gets up to leave to hear a friend who’s playing at the Bottom Line. Rivera goes with him, and when they get to the club Dylan’s friend is Muddy Waters. Soon enough, Dylan is pulling Rivera up on stage with him and Muddy, saying “Now I want to bring up my violinist.” Rivera replaces Eric Clapton on Desire. As she tells Padgett: “The reason I flew to New York to break into music was not to be the string-section sweet sound that violins have been known for. The way I heard violin, I could replace a lead guitar.”

Barry Goldberg, the organist who “went electric” with Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, expresses a sentiment about playing with Dylan that Padgett says he heard a lot in the interviews: “I was feeling like I was touched by Bob, by the magic, and that really has never left me to this day. Once you experience something like that with someone like Bob, it doesn’t rush off. It stays with you.”

Benmont Tench puts it this way: “You can read about Bob’s life, and you can pay attention to what he says, and you can learn from it, but when you play music with somebody of that caliber, you learn something entirely different. It can only be passed on by that person. And those of us who have had the opportunity to play with that person can pass on what we took away.”

With that, Tench sums up the best reason for picking up Padgett’s book. This is no staid and exhaustive biography or a ponderous tome or music criticism. Pledging My Time brings Dylan to life in a way that he’s never come to life before.

Ray Padgett’s Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members was published June 27 by EWP Press.