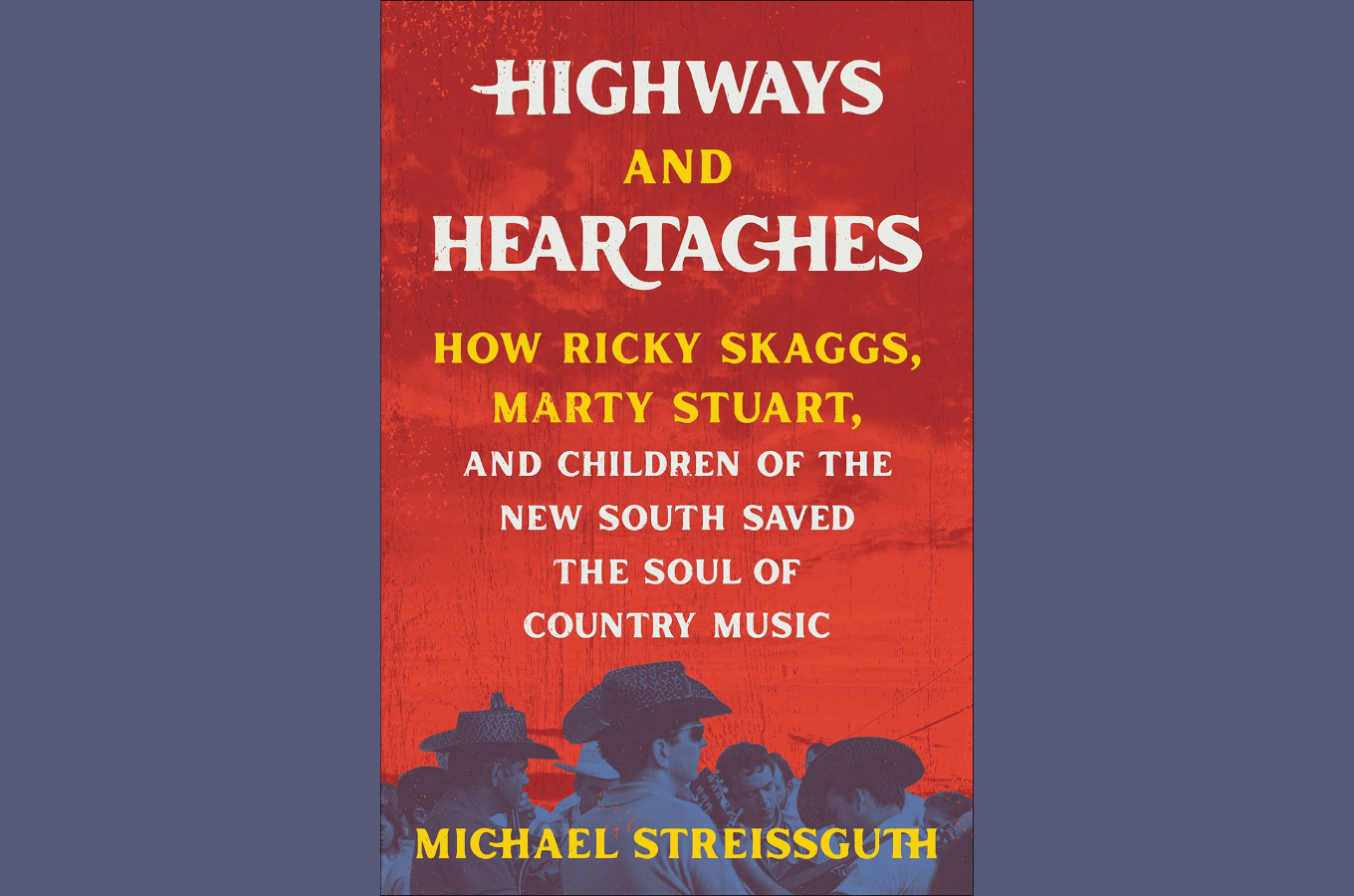

THE READING ROOM: Country’s Evolution Told Through Careers of Ricky Skaggs and Marty Stuart

Like Marty Stuart’s rockabilly guitar licks and Ricky Skaggs’ lightning-fast mandolin runs, music historian and critic Michael Streissguth’s tour-de-force music history, Highways and Heartaches: How Ricky Skaggs, Marty Stuart, and Children of the New South Saved the Soul of Country Music, scampers through the musical landscapes that influenced these two musicians and that they themselves have helped shape.

Streissguth, whose previous books include Johnny Cash: The Biography and Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris and the Renegades of Nashville, traces the lives and careers of Skaggs and Stuart in a dual biography, alternating chapters to focus on each musician’s evolution from the bluegrass circuits to the hallowed stages of country music as they cross paths with country and roots musicians including Ralph Stanley, Lester Flatt, Clarence White, J.D. Crowe, Johnny Cash, Emmylou Harris, and Linda Ronstadt.

Although Skaggs famously played mandolin on stage with Bill Monroe when he was 6 years old, he didn’t hit the circuit as a player until he was a teenager, when he and another Kentucky native son, Keith Whitley, joined Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys in 1971. Before the decade was over, though, he had cycled through two transformative bluegrass bands: the Country Gentlemen with Doyle Lawson, Bill Emerson, and Jerry Douglas, and J.D. Crowe’s New South, which included Tony Rice and Douglas. Skaggs soon left to form his own band, Boone Creek, which featured a young Vince Gill on pedal steel. Before the ’70s were out, he was playing mandolin and fiddle and singing harmony in Emmylou Harris’ Hot Band.

Streissguth portrays an ambitious young Skaggs following his creative instincts, always wanting to do more with the music. “Every time that I made a move from one band to the next,” Skaggs tells Streissguth, “it was like I saw myself climbing up the ladder, and it wasn’t necessarily the ladder of success. But it was the ladder of knowledge and wisdom, and it was also the knowledge of music, different styles of music that I was getting into my head. And so I saw the New South as a stepping-stone to maybe having something someday for myself.”

In 1982, Skaggs released his second album, Highways and Heartaches. It became a platinum seller, blending bluegrass and country and ushering in what became known as “new traditionalism” in country music. Skaggs watched the third single from the album, “Highway 40 Blues,” top the charts. “While introducing young listeners to great songs of yore — such as Bill Monroe’s “Can’t You Hear Me Callin’” — he showcased them in a polished musical framework built on familiar country music instruments, energized at times by western swing and rockabilly tempos and, always, electric guitar and drums,” Streissguth writes. “It was a new dimension in country music, as revolutionary as producers Chet Atkins’s and Owen Bradley’s countrypolitan arrangements in the 1950s and 1960s, and Waylon’s and Willie’s outlaw country of the 1970s.”

Meanwhile, a young picker out of Philadelphia, Mississippi, was playing guitar and mandolin in gospel group The Sullivans. In 1971, he had traveled to Indiana’s Bean Blossom festival, where he happened to meet Skaggs. But Stuart had come to the festival, Streissguth explains, to seek “an audience with Lester Flatt, the legend whose gently creased face was so familiar from the loop of Flatt and Scruggs’s television programs he had watched in the 1960s. He hustled over to Flatt’s bus to say ‘hello,’ and then he followed his entourage to the stage. Later, he’d write, ‘He walked very slowly through the dust and the sea of campers. People sort of changed as he passed, like the effect of a preacher walking through a poker game. Musicians, hippies, old folks, and kids all wanted to just touch him.’ Flatt seemed as distant from Stuart’s reality as Elvis Presley, but at Bean Blossom, the young admirer closed the gap by getting to know Roland White, the mandolin player in Flatt’s Nashville Grass.”

White was instrumental in ushering Stuart into Flatt’s band in 1972. “We were in that park in Glasgow, Delaware, for two days and four shows, and at the end of the four shows, Lester offered me a job,” Stuart tells Streissguth. “I was supposed to be back home in school about two days later, and so I started calling my parents and I said, ‘You’ll never guess what happened? Lester Flatt offered me a job.’ They said, ‘Well, that’s nice, but you have to come home.’ I begged and pleaded, and Lester said, ‘If you stay on this week you can play the Grand Ole Opry with us and play on our Martha White radio show.’ So that was begging rights to get me to stay one extra week.”

By the mid-1970s, when Stuart looked around him he saw that Emmylou Harris and The Eagles, among others, “were moving into the future by finding rock and country’s natural connections.” Stuart had come to know guitarist Clarence White, who had re-formed The Kentucky Colonels with his brother, Roland. “Clarence just seemed like almost a North Star figure because he was a bluegrass guy that had pretty much been raised on the same stuff as me but somehow had made it beyond that, and he became a rock star and played for big crowds and was on the cover of a Columbia record album,” Stuart says in the book. “He dressed cool, and people from Jimi Hendrix to Jimmy Page knew Clarence, but at the same time so did Doc Watson. And that California vibe surrounded him, and he was the template on how to live a life and get beyond just playing at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville for somebody else.” Stuart looked to White because he was rooted in traditional bluegrass, but White had traveled beyond it, in The Byrds (especially their Sweethearts of the Rodeo album) and in the records he was playing on, like those of Jackson Browne and Linda Ronstadt.

Although he joined Johnny Cash’s band in 1980, Stuart “had hoped to parlay his status as a former member of the Nashville Grass to burnish his songwriting skills and improve his vocal performance on the way to a solo career in the mold of Ricky Skaggs,” Streissguth observes. “But although plenty of people around Cash in the late 1970s and early 1980s were establishing recording and touring careers — Rosanne Cash, Carlene Carter, and Rodney Crowell, most prominently — the Cash band was never a pipeline.” After Stuart left Cash’s band in the mid-’80s, he released his debut album, but it wasn’t until 1989’s Hillbilly Rock and 1991’s Tempted that Stuart hit a groove, delivering the kind of music that would make his mark on the country music world.

As Streissguth reminds readers, both Skaggs and Stuart preserve tradition and innovate within that tradition. “Together they have come to represent tradition on the face of commercial country music,” he writes. “The two musicians seem to delight in that role, but it belies their experimentalism, apparent in Stuart’s recent country-rock collaborations with Chris Hillman and Roger McGuinn of the Byrds, and Skaggs’s buoyant team-ups with Ray Charles and Bruce Hornsby and his trippy sacred album Mosaic. An even better example of their fearlessness appears in a clip from Skaggs’s Monday Night Sessions on cable television, originally broadcast in 1997, in which he and Stuart, electric guitars strapped on tight, joined forces with rockabilly great Brian Setzer in a burning-house performance of ‘Rock This Town’ that briefly reorders country music consciousness.”

Highways and Heartaches: How Ricky Skaggs, Marty Stuart, and Children of the New South Saved the Soul of Country Music often feels a little out of balance, as if there’s more Skaggs than Stuart. But Streissguth’s sparkling prose provides a mesmerizing sketch of both musicians and the manifold ways they have contributed to the ever-changing sounds that flow into the raging river of country music.

Michael Streissguth’s Highways and Heartaches: How Ricky Skaggs, Marty Stuart, and Children of the New South Saved the Soul of Country Music was published by Hachette on Aug. 8.