JOURNAL EXCERPT: One Guitar’s Journey from Clarence White to Tony Rice to Billy Strings and Beyond

EDITOR’S NOTE: Below is an excerpt from a story in our Winter 2023 issue of No Depression. You can read the whole story — and much more — in that issue, here. And please consider supporting No Depression with a subscription for more roots music journalism, in print and online, all year long.

It was a cool evening last March in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and Billy Strings wanted the crowd to quiet down. After two rollicking sets at Lawrence Joel Veterans Memorial Coliseum, he and his band had returned to the stage and gathered around a single mic to give the 14,665 gleeful fans an encore. The crowd responded with the whoops and yells expected for an artist whose popularity was exploding, but Strings wasn’t having it.

“We’re going to try to get it real quiet in here,” Strings said, “because I want you to hear Tony Rice’s guitar.”

The 31-year-old Strings had been barnstorming the country on a tour that continued through the summer. But even as his athletic brand of bluegrass fused with psychedelic rock was filling arenas with new fans, he had made sure to show his respect to the elders of acoustic music. The night before the Winston-Salem show, in fact, he played a 45-song tribute to Doc Watson on what would have been the guitar legend’s 100th birthday, and later was filmed playing one of Watson’s best-known guitars, Ol’ Hoss, at Bryan Sutton’s Blue Ridge Guitar Camp. Last February, he and his band donned pale suits and ribbon ties for a sold-out show at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville. In April, he released a song with Willie Nelson, sang on stage at Nelson’s 90th birthday celebration, and posted a video of himself playing Nelson’s iconic guitar, Trigger.

“I just grew up worshipping all these bluegrass guys,” String begins, calling during a break in his international tour that runs through New Year’s Eve. “I never got to meet Tony Rice. But obviously he’s one of my heroes, and as far as I’m concerned one of the greatest guitar players to ever live.”

Rice died on Christmas Day 2020, and though he hadn’t performed in years due to health problems, serious fans still felt the sting of his loss. His guitar — a vintage Martin once owned by his flatpicking hero, Clarence White — was almost as beloved as Rice was. Here was an instrument that links nearly a century of American music; a guitar owned by not one, but two legendary innovators whose technique and tone influenced every bluegrass guitarist after them; an artifact treasured for its unique sound as well as unlikely tales of survival. To the serious bluegrass fans in the crowd, it was a thrill to see the iconic instrument in public for the first time in nearly a decade; to the casual fans, of which there were likely many more, it was a window into the past of a genre that is forever trying to hold onto it.

“It’s probably the most important guitar in the history of bluegrass and probably in a lot of acoustic music, period,” says Tim Stafford, guitarist for Blue Highway and the co-author of Rice’s authorized 2010 biography, Still Inside: The Tony Rice Story.

The guitar’s appearance also stoked an ongoing debate about the fate of an instrument that in addition to being historically important is undeniably valuable. Should it go to one of the guitarists in Rice’s family or circle of friends with whom he made music? Should it go to a museum that would keep it safe for posterity? Or is there a way it could be made available for emerging artists to play so that they and their fans can experience for themselves what made it so special?

On the internet message board Acoustic Guitar Forum, one fan summed up the feelings of many in the bluegrass community: “Just as long as it doesn’t end up in a finance bro’s collection.”

Guitar Rescue

Rice referred to his Martin as the “holy grail” of acoustic guitars. By the mid-20th century, Martin’s hulking large-body dreadnoughts were becoming the guitar of choice for bluegrass and country performers, in large part due to their booming sound. White’s D-28 model with herringbone binding was made in 1935, the first year the company had offered it in their catalog, but a well-preserved instrument this was not: A music-store trade-in when White and his brother acquired it, the guitar sported a mismatched, oversized fretboard and a mysteriously enlarged sound hole.

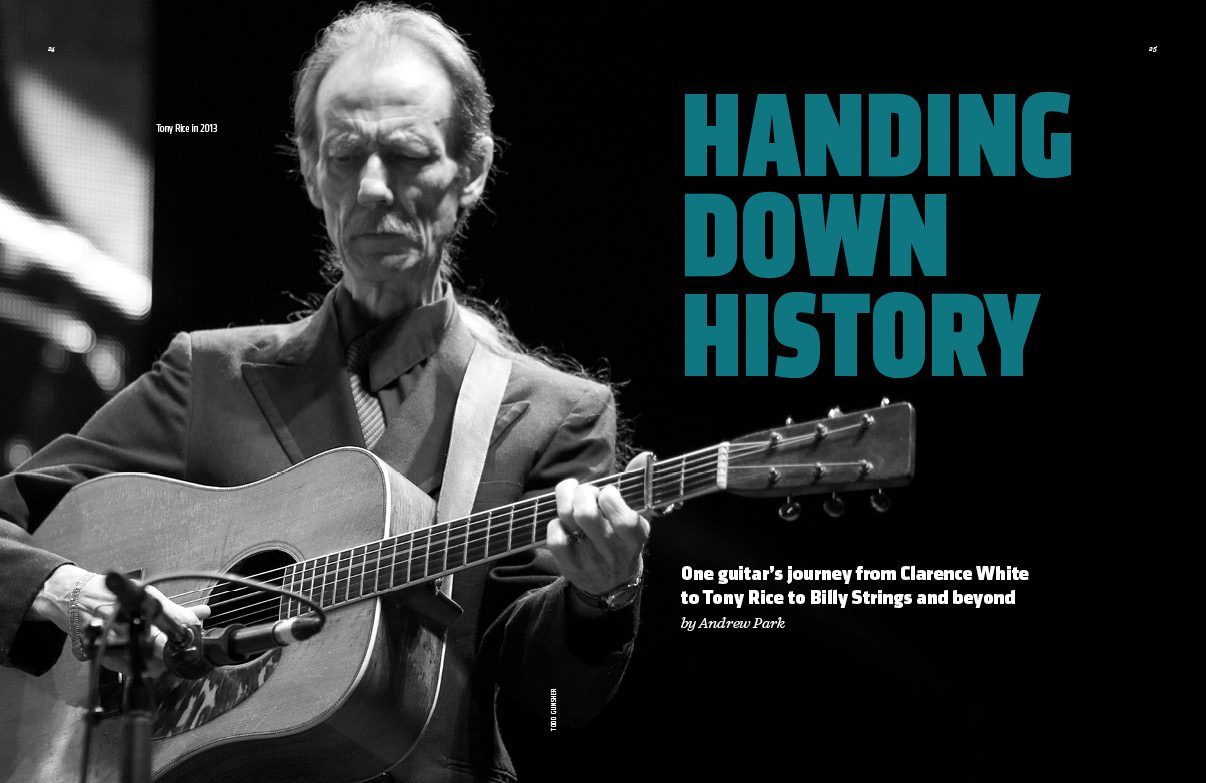

Tony Rice at MerleFest 2012 (Photo By Amos Perrine)

By his own account, Rice lucked into owning the instrument. He had first encountered it when he met White in 1960; Rice was just 9 years old and White was 16, and both were already making string music with their families in Southern California. White’s guitar caught Rice’s eye, and White asked him if he wanted to play it. From then on, whenever they were together, White always offered it to him to play.

White, who counted both Watson and jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt as early influences, went on to revolutionize bluegrass picking with The Kentucky Colonels, a band comprised of his brothers Roland on mandolin and Eric Jr. on bass (replaced in 1961 by Roger Bush), as well as Billy Ray Latham on banjo and LeRoy Mack on dobro. White stood out in The Kentucky Colonels, wowing fans with his lightning licks and complex rhythm, and proving that the acoustic guitar could lead a bluegrass band just as well as a banjo or mandolin.

As Bush recalls, “Tony Rice, he was never an appointment or a call-ahead. He’d just show up where we were sometimes and we’d have to sit back in the dressing room and listen to him and Clarence go back and forth. And I was just trying to see who could get it the hottest, and between the two of ’em, it’s a wonder the place didn’t burn down.”

In 1965, though, White put his D-28 up as collateral on a loan and never got it back. His tragic death after being hit by a drunk driver in 1973 cut short a career that had led him to go electric and join The Byrds before coming back to play bluegrass with his brothers again.

Two years later, Rice found out the old guitar was in the possession of the man who had taken it as White’s collateral. A bluegrass fan himself, the man had stashed it under a bed in his home in California. It took Rice one phone call to track him down, and he flew out the next day and bought it off him for $550. On the return trip, Rice retrieved the guitar at his connection and re-checked it, lest it get lost in transit. There was more than just sentimentality for his youth behind Rice’s attachment to the guitar: Rice revered White and frequently cited him as an influence, though he claimed he could never play as well.

“Clarence put that D-28 in his hands, and he was in awe of Clarence and loved him with such respect,” says Caroline Wright, a longtime bluegrass journalist and co-author with Stafford of Still Inside. “I think he felt obliged to seek out that guitar and resurrect it.”

Sharing the Sound

It didn’t take long for Rice to establish himself as a worthy heir to White — prodigiously talented, wildly inventive, and prone to follow his curiosity beyond bluegrass’ traditional boundaries, including his foray into jazz in the late 1970s. The D-28 proved to be well-matched to Rice’s speed and precision and produced a clear, expressive tone that became his signature. It would become a totem of his genius for fans and would-be imitators.

Rice, tall and slim, with the taciturn bearing of an Old West sheriff, wasn’t comfortable with hero worship. But he developed a connection to the guitar he would later describe in Still Inside as visceral and at times supernatural. He played other guitars, including custom collaborations with Santa Cruz Guitar Co. that, while not copies of his Martin, did mimic certain elements, including the enlarged sound hole, but he always came back to the one he dubbed The Antique or The Herringbone.

His deep connection did not stop Rice from handing the guitar to friends and fellow musicians to experience its unique action just as White had the first time they met. Kari Estrin, who was Rice’s agent and manager from 1981 to 1985, recalls him offering it to her to jam on when they were together; Rice’s brother Wyatt, who recorded with him and performed as a member of The Tony Rice Unit, also played it frequently.

Stafford remembers when he was playing with Alison Krauss and Union Station at the 1990 Winterhawk Bluegrass Festival (now the Grey Fox Bluegrass Festival) and he broke a string right before an encore: Rice was waiting to go on after and handed him The Antique. “I was so freaked out, I could barely play, but I did, I played the encore with The Antique,” Stafford says. “I remember Alison grinning like a big possum, she thought that was really, really cool. And, and it was very cool of him to do that.”

More famously, Rice can be heard offering it to Jerry Garcia on The Pizza Tapes, mandolin virtuoso David Grisman’s recording sessions with his two friends. Garcia, who had been friends with White in the 1960s, can be heard saying that “Tony gets a better tone actually than Clarence did.”

“The thing is, I’m so eager to have kids and guitar aficionados play it,” Rice wrote in Still Inside. “I don’t think I’ve ever turned anybody down that asked me if they could hold it or play it. I wouldn’t deprive anybody of that pleasure.”

The guitar’s history was one of remarkable survival. White had inexplicably shot at it with a pellet gun, used it as an ashtray, and filled it with wet sand, and once accidentally drove over it with his band’s van, according to a seminal 2007 article on the instrument in Fretboard Journal. In 1993, during a tropical storm, it spent hours submerged in floodwaters after Rice had to abandon his Florida home by boat.

That same year, Rice began to have difficulty singing on stage, the result of damage to his vocal cords that he attributed to straining beyond his natural range, and he stopped singing publicly in 1994. He continued to play guitar and toured off and on throughout the 2000s, but his playing was slowed by pain and weakness in his elbow and wrist, likely repetitive stress from years of fast picking. His last public appearance came in 2013 at his poignant induction into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame, during which he played The Antique on “Old Train” with Wyatt Rice, Ricky Skaggs, Jerry Douglas, Sam Bush, and Todd Phillips.

In remarks beforehand, the raspy-voiced Rice stunned the audience by summoning his natural baritone for a few minutes and talked optimistically of regaining the physical strength to perform again: “I figure maybe if I can keep this up, that one day again maybe I’ll be able to do what I have missed at times for 19 years, which is to express myself poetically through music. And if I can keep this momentum going, maybe one of these days, I’ll be able to do that.” Sadly, he never was.

Back on Stage

Behind the D-28’s reappearance at Billy Strings’ show in March was Lucas White, a young Nashville musician who had befriended Rice “before he could drive” and remained close with his family. He had contacted Strings’ camp, offering for Rice’s widow, Pamela Hodges Rice, to come to his shows in Winston-Salem and bring The Antique. Strings is the “cultural standard for bluegrass right now,” White says, and “the biggest guitar player probably on the planet right now.” He continues, “I thought it was very appropriate with his respect, with his musicianship, with his humility, with his different style even.”

In an Instagram video of the scene backstage before the show, Strings groans when he sees the guitar, seeming to feel the weight of the moment, and then holds it gingerly before trying his hand at picking it. “This thing is a beast,” he says. Remarkably, it still bore the last set of strings Rice ever put on it, the nickel-alloy variety he favored. Strings spent about 30 minutes playing it and passing it to bandmates before Pamela, sitting beside him, offered to let him take it on stage that night. “I think that guitar likes you,” White recalls her saying. She had only one request, that he mention a festival named for Rice that she was helping inaugurate at Camp Springs Bluegrass Park (where Rice was discovered in 1971) in central North Carolina later that spring.

Strings remembers those backstage moments viscerally too. “It was hard to even pull it out of the case,” he says. “I just wanted to sit there and look at it for a second.”

When he first began to strum The Antique, he was surprised he didn’t get much of a sound out of it. It wasn’t until he lightened up his touch that its voice started to come out.

“I grew up seeing that guitar, and I’m like, that thing must be a cannon. It’s really not. Tony Rice was the cannon,” Strings continues. “It was incredible to just check the guitar out, to try to feel Tony’s soul through it.”

And he certainly did his best to convey that on stage. After quieting the crowd, Strings ripped through three Rice staples — “Likes of Me,” “Tipper,” and “Freeborn Man” — raising the swollen sound hole up to the microphone frequently to make sure the audience could hear it speak. He made no attempt to sound like Rice or imitate his understated style of picking, and no one seemed to mind. It was enough to see that old guitar in the hands of bluegrass’ breakout star, finding its way to greatness once again, if only for one night.

Loans and Legacy

Almost as soon as they learned of Rice’s death in 2020, fans began to speculate about what would happen to his beloved guitar. Rice had written in Still Inside that he had told his lawyer it should go to Billy Wolf, his longtime engineer, “who would know who its next logical owner should be. Probably Wyatt, but I don’t know.”

But rumors soon began to spread that it would be sold to a museum or a collector. For some in the bluegrass community, that was heresy. Rice had talked of receiving substantial offers to sell it and said that he traveled with a gun in case someone tried to steal it. But even amid his well-publicized financial problems in the last decade of his life, when he was no longer able to perform and royalties had dwindled with the shift to digital music, he balked at the idea that he might part with it, no matter the price. With his death, though, others recognized the hard truth — that years of medical bills and other family trials might have left his survivors in need and with few assets available.

The guitar’s ultimate fate remains unknown, but friends and fellow musicians are hopeful that putting it into Strings’ hands is a sign that the instrument won’t be locked away in a vault and might be played again, publicly and more frequently. They point to the tradition in classical music of patrons loaning 18th-century Stradivarius instruments to promising violinists, certain collectors of important rock guitars who will offer them to musicians who couldn’t afford to own one, and even the viral moment last year when Lizzo performed with a 200-year-old crystal flute owned by James Madison borrowed from the Library of Congress.

Around the time Strings played The Antique in Winston-Salem, White also arranged for Sam Grisman (son of David Grisman) to play the instrument in a visit to Pam Rice’s home in Reidsville, North Carolina. Grisman, whose current band celebrates the musical legacy of his father and Garcia, says he felt like he was “hallucinating” just being in its presence: “As much time as I’d spent around Tony and that guitar as a kid, it never dawned on me how much of a piece of American musical history that particular instrument is.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uUVMw1pSV3s

Arranging to loan out an instrument as delicate and valuable as Rice’s D-28 would be complicated and risky. Still, says Estrin, “I think it’s brilliant and it’s great of Pam to recognize that and to seize that opportunity. … Some people probably have never heard of Tony Rice. But what she’s doing there is continuing that legacy, continuing that history in a really beautiful way.”

Additionally, says Stafford, it would continue a tradition that started with that instrument more than 60 years ago: “It’s the same thing that Tony had in mind when he let people play it, and the same thing that Clarence had in mind when he let Tony play it. It’s connecting with history, and that never leaves you. So if we want to make more fans in bluegrass and we want to keep people interested in the music, I think that’s one way you do it.”