THE READING ROOM: New Book Follows Blind Boys of Alabama Along the Gospel Highway

Since 1939, The Blind Boys of Alabama have been riding up and down the gospel highway in the US, “wrecking houses” — channeling the Holy Ghost through their music and rousing congregations to leap, run up and down and dance in the aisles — in every town they visited.

During their long reign as the kings of the gospel quartet style, the group has carried their hard gospel sound to the world, touring unceasingly and playing to large crowds. Between 2002 and 2005, they garnered four Grammy awards, and in 2009 they won a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. The Blind Boys have performed or recorded with artists such as Lou Reed — whom longtime leader Clarence Fountain said, with some affection, “could not sing his way out of a paper bag” — Prince, Bonnie Raitt, and Ben Harper. The group’s version of Tom Waits’ “Way Down in the Hole” became the theme song for the first season of the HBO series The Wire. The group’s version of the classic hymn “Amazing Grace,” sung to the melody of “The House of the Rising Sun,” illustrates the group’s canny nod to the fine line between the Saturday night ecstasies of rock and roll and the Sunday morning bliss of Holy Spirit union.

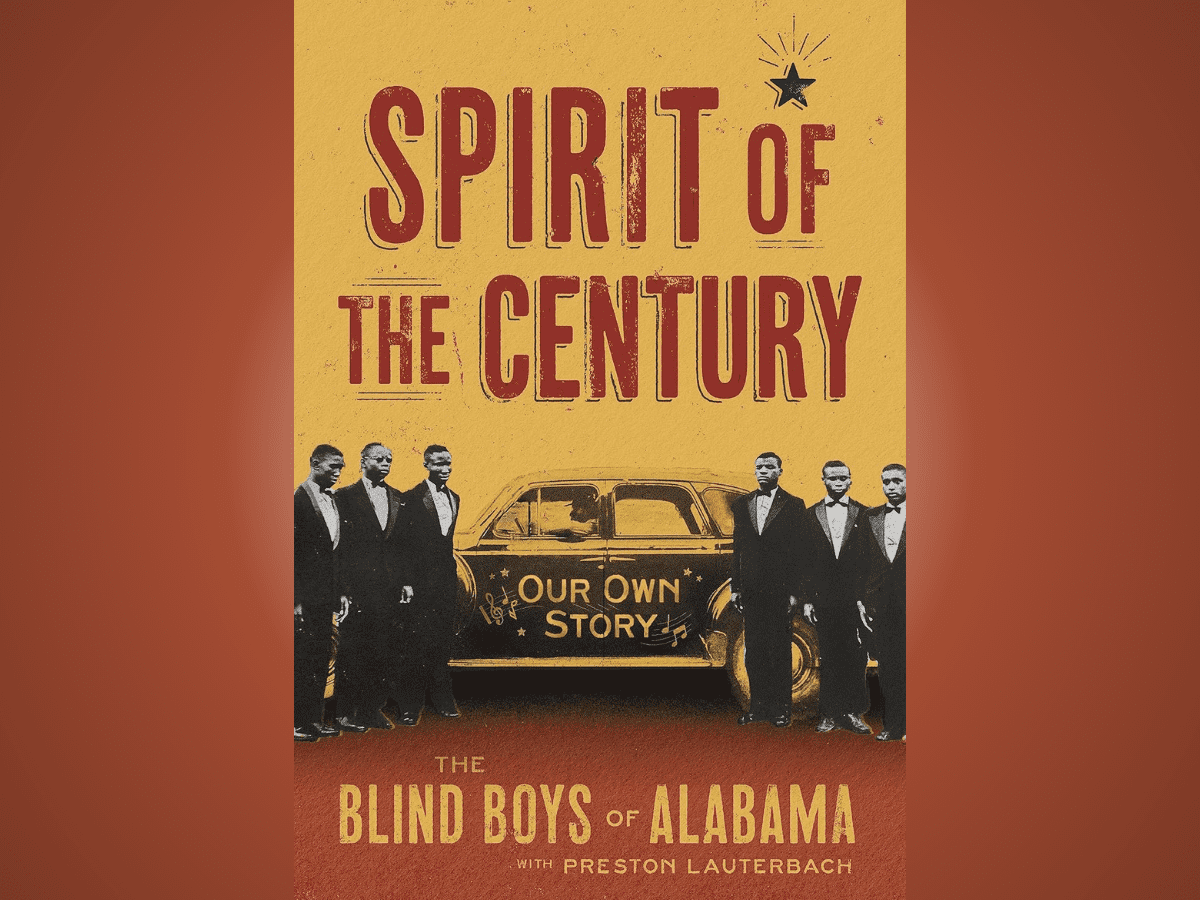

Now, in Spirit of the Century: Our Own Story, the Blind Boys of Alabama, along with Preston Lauterbach (author of The Chitlin’ Circuit and the Road to Rock ’N’ Roll), give their version of the journey. Drawing on interviews with members of the group and their friends, musical collaborators, and family, Lauterbach takes readers for a ride along the gospel highway with the group, tracing its evolution from its origins as The Happy Land Singers to The Blind Boys of Alabama. Although the Blind Boys are listed as the book’s authors, Lauterbach tells the stories in his voice, and the book offers a thoughtful and insightful look at the wider history of gospel quartets during the golden age of gospel music and how the Blind Boys grew and thrived in that environment.

The group formed at the Alabama School for the Negro Deaf and Blind in Talladega, Alabama, an abusive institution that trained the boys to make brooms. Several of the boys yearned for freedom and heard it in the music of gospel quartets; they would “escape” from the school in the afternoons and walk single file holding hands to a local country store where the proprietor allowed them to gather around the radio and listen to the gospel show from Birmingham, Echoes of the South. The boys heard the great Birmingham quartets including The White Rose Singers, The Ensley Jubilee Singers, and The Blue Jay Singers, with local celebrity Silas Steele on the show. These five boys — Clarence Fountain, George Scott, Velma Bozman Traylor, Johnny Fields, Olice Thomas, and J.T. Hutton — formed The Happy Land Singers. Another boy, Jimmy Carter, wanted to join them, but his parents would not let him travel with the group. Carter, who eventually sang with The Dixieland Blind Boys and The Five Blind Boys of Mississippi, finally joined The Blind Boys of Alabama in 1982.

In their early days, the group practiced the jubilee tradition of gospel music made famous by The Fisk Jubilee Singers. This style of singing, which the boys heard in the Birmingham quartet tradition, involved smooth, close harmony, with “four or five voices singing as one, until one or more of them peeled off from the rest, breaking time or shifting texture only to return beautifully to the fold like the feathers of a wing,” Lauterbach writes. Eventually, though, The Happy Land Singers discovered that they needed an edge if they were going to compete with other quartets in contests held in Birmingham and in other cities. They developed the hard gospel sound, in which a lead singer would improvise, interject moans and screams, and “bring the intensity of fire-and-brimstone preaching to the rhythmic, harmonious backdrop of the jubilee quartet style.”

In April 1948, The Happy Land Singers — minus Velma Traylor, who died in 1947 — engaged in a quartet battle with The Five Blind Boys of Mississippi billed as “The Song Battle of the Century” at Harlem’s Golden Gate Auditorium. The ads for the event touted these Blind Boys of Alabama as “Acclaimed World Champions,” and the group began appearing less as The Happy Land Singers and more as The Blind Boys of Alabama, the name under which they would record for Art Rupe’s gospel label Specialty Records. After Velma Traylor died under tragic circumstances, the group continued on and various members joined and left.

George Scott carried the group to a higher level with his backing vocals. “For the Alabama Blind Boys, George Scott created a backing vocal identity that would be with the group for decades to come,” Lauterbach writes. “Scott, Thomas, and Fields sang resourcefully, driving the song’s rhythm and changing pace with sharp pauses, accenting and punctuating beats with sudden increases or decreases in volume.”

Fountain and Scott drove each other, developing the Blind Boys’ singular sound: “In terms of a stylistic breakthrough in the lead department, Clarence Fountain busted out what [guitarist Sam Butler Jr., who joined the group in 1972,] called the ‘sanctified squall.’ … Musically, Fountain’s sacred squall and Scott’s muscular jump-style backing vocals push the song in classic Blind Boys fashion. …This sound had importance not only in distinguishing the group from other quartets on the road but also in authenticating them to listeners. …The Blind Boys’ signature sound, particularly that strapping, syncopated back end, clearly influenced secular vocal quartets Billy Ward and the Dominoes and the Falcons.”

Lauterbach points out, too, that “Blindness figures heavily into their unique perspective as it does their music. According to one former member from long ago, since the Blind Boys don’t see their audience, they have to feel them. He said that their sound comes from the heart and not from anything external. As Jimmy Carter says to fire up their audience, ‘I can’t see you; so I need to hear you.’”

Every page of Spirit of the Century teems with stories of the group’s challenges and triumphs, and Lauterbach reveals how “The Blind Boys deliver unvarnished truth on record, on stage, and in conversation.” One of the best features of the book is an appendix devoted to “listening to the Blind Boys of Alabama and the Gospel Highway Quartets,” which calls attention to the neglected Birmingham quartet tradition. Spirit of the Century is a must-read for fans of The Blind Boys of Alabama and for fans of gospel music.

Spirit of the Century: Our Own Story by The Blind Boys of Alabama, with Preston Lauterbach, was published March 19 by Hachette.