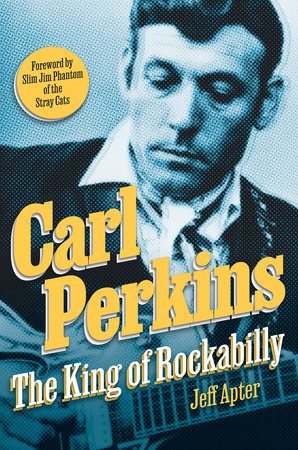

THE READING ROOM: Jeff Apter on ‘Carl Perkins: The King of Rockabilly’

“Well, it’s one for the money, two for the show/three to get ready, now go, cat, go.” That’s just what Australian music writer Jeff Apter (Don’t Dream It’s Over), does in his affectionate, straight-ahead biography Carl Perkins: The King of Rockabilly (Citadel/Kensington, November 26). While “Blue Suede Shoes” became the hit that propelled Carl Perkins to the top of the charts, selling 250,000 copies just one month after its release in January 1956, and became the song with which he became most associated, Perkins went on to write songs such as “Daddy Sang Bass,” “Honey, Don’t,” and “Dixie Fried” that were cut by many other artists, including Johnny Cash, The Beatles, and Elvis.

Drawing on archival research, Apter traces Perkins’ life from his childhood as a sharecropper’s son in rural Tennessee to his early days at Sun Records, including his ups and downs with addiction, as well as his enduring friendships and musical collaborations with Cash, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and many others. By the time he was ten, Perkins could pick up to 300 pounds of cotton per day, but the field shouts and call-and-response singing of fellow field hands made an impression on him. The young Perkins wondered if music might be an escape from the drudgery of picking cotton, and he wrote in fourth-grade that he wanted to be “a big radio star.” By this time, Perkins had already received his first guitar, and his uncle, who was his first teacher, told his nephew: “‘That guitar can take you miles away from these cotton fields, boy, if you work on it.’” Sure enough, Perkins rode the rhythm of those guitar strings all around the world, from Memphis to London, and beyond.

In late 1955, Perkins wrote the song that elevated him into the stratosphere and gave rock music one of its standards. Playing one of the honky tonks near his town, Perkins overheard a man say to his dance partner: “‘Uh, don’t step on my suedes.’” Those words stuck with Perkins as he thought: “‘You fool, that’s a stupid shoe, and that’s a pretty girl, man.”” He went home and wrote down the words and strummed a simple tune to accompany the lyrics. The next day he called Sam Philips at Sun Records, where he’d already been recording, and said: “‘Mr. Phillips…I wrote me a good song last night.’” By late 1956, the song blared on country, pop, and R&B radio, and Phillips told Perkins he had a hit on the song.

Perkins was riding high, until a car accident in March laid him low. He had been scheduled to perform “Blue Suede Shoes” on the Perry Como show, a big break for the singer, just days after the horrific accident, which laid him up for several weeks. During that time, he watched Elvis perform the song on the Milton Berle television show, Perkins felt like he had been left behind, knowing Elvis already had a huge following and that fans were likely to gravitate to Presley’s version and not to Perkins’ own. By the end of the 1950s, Perkins’s commercial success had dried up, though he still continued to write.

In 1960, Perkins received a new lease on his musical life from a group of young musicians in Liverpool who idolized Perkins and his music. The Beatles latched onto Perkins’ songs as they developed their repertoire and honed their live performances in the early 1960s. During their first shows in Hamburg, Germany, in August 1960, the Beatles delivered their own versions of Perkins’ “Honey, Don’t” and “Blue Suede Shoes,” and they went on to record these songs as well as other Perkins compositions such as “Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby,” and “Matchbox.”

Members of the Beatles developed close, lifelong relationships with Perkins. In 1993, Perkins sent one of his classic Fender Stratocasters to McCartney’s son, James, as a sixteenth birthday gift; the next year, Perkins sent a six-string to Dhani Harrison, George’s son, when he turned sixteen. When Perkins was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1999, McCartney led a band that included Eric Clapton, Bonnie Raitt, Robbie Robertson, and others in a performance of “Blue Suede Shoes.” Indeed, McCartney once said that “if there were no Carl Perkins, there would be no Beatles.”

Just before his death on January 19, 1998, following complications from a series of minor strokes, Perkins was asked how he would like to be remembered. “He paused before responding, then quoted from a plaque hanging on the wall of his home in Jackson. It read: ‘Within these walls I’ve written my songs. I’ve done you right and I’ve done you wrong. Let it be said when I’m gone that he smiled and wasn’t ashamed to play.’”

Through a series of short chapters, Apter provides a useful introduction to Perkins and his life and music. Carl Perkins: The King of Rockabilly will appeal primarily to fans of Perkins, but the book’s short and well-paced chapters also serve as a useful introduction to Perkins and his music.