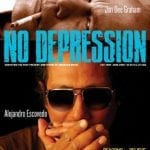

Alejandro Escovedo – How friends, fans, and his idols helped inspire his return to music

Alejandro Escovedo no longer takes anything for granted. Always a courtly gentleman with a soft-spoken manner, he begins the interview by asking, “How are you?”

Fine, Al, great. Couldn’t be better. And you? How are you feeling?

“I’m doin’ very well,” he replies, with a moment’s reflection. “Very well. I’m limping around a little bit. Something happened to me last night. I don’t know what. I had something in my pocket and slept on it. Or sat on it. But no, I’m fine. Doin’ good.”

After what Escovedo’s been through, a little limp is nothing. But he acknowledges that asking him how he feels is more than a standard greeting. And it requires something more than a pat, perfunctory response. People want to know how he feels, and he’s finally ready to tell them. Because he’s learned the lessons of the deathbed. Each day is a gift. Each breath is a blessing. Tomorrow carries no guarantee.

Following his April 2003 collapse from hepatitis C, cirrhosis of the liver and internal hemorrhaging, Escovedo spent much of his extended recovery avoiding such questions, laying low, refusing all requests for interviews.

For what could he say?

How are you feeling?

I’m feeling awful.

As someone who’d long enjoyed living in the spotlight — he was a star in Austin years before the rest of the world caught on — he now wanted no part it. After returning from his emergency-room hospitalization and subsequent convalescence in Arizona that spring, he stayed away from Austin. He lived on the outskirts of San Antonio and then moved to the small Texas Hill Country town of Wimberley, about an hour southwest of Austin, where he’d lived for more than twenty years as one of the city’s most prominent and accomplished musicians.

Austin had too many people he knew, too many memories, too many temptations to which he’d frequently succumbed and now knew he must avoid. To drink meant to die. He felt weak, and he had no confidence that he would ever feel any stronger. He had to focus all his energies, his entire being, on getting better.

Questions could wait. Music could wait. A career could wait. Maybe there would be no more career. At least not in music. But if music was no longer an option, what would a guy in his 50s possibly do? He’d spent a few years working at Waterloo Records during his holding-pattern disillusionment between the late ’80s disintegration of his band the True Believers and the solo recording career he would launch in the early ’90s. But he didn’t have any interest in going back to being a middle-aged clerk, selling other peoples’ CDs.

Making music had become so much more than his livelihood. For three decades, music had been his mirror. It had given him his identity, or at least determined how others perceived him.

Attracting and expanding a rabidly loyal fan base, he’d become accustomed to being the center of attention. Not demanding that attention — his charisma was more the quiet, understated kind — but commanding it. He was a performer at heart, and the performance extended well past last call. Wherever he went, wherever the party led, Alejandro held court. He was the coolest guy in the room. And it was music that had made him so cool.

Few had bought more deeply into the rock ‘n’ roll mythos than Escovedo: the reckless excess, the boys’ club bravura, the endless nights, the trash-flash romance of the bands he loved most, from the Faces to T. Rex to Mott The Hoople. Another margarita, another shot of Jagermeister, another party, another dawn — that was rock ‘n’ roll. Music wasn’t something you played. It was how you lived. It was who you were.

“It’s a weird world we live in, where desire, passion, and all these temptations, if you want to call them that, are abundant,” says Escovedo, now 55. “And I totally threw myself into that life. You know this; you knew me when I was living in that little room [in Austin, during the early ’90s, a period of turmoil and tragedy that would inspire much of the material on his early solo albums]. I experimented with a lot of stuff. And I never wanted to shy away from having a good time.”

So, Escovedo had lived for his music, and the music had killed him. Or was threatening to. During the first stages of what would prove to be a lengthy and expensive recuperation, he felt betrayed. He had no desire to even touch a guitar, let alone write a song. He had no idea who he was or what he could become, only that he no longer could be who he’d been. That man was a dead man.

“I turned my back on me, and I faced the face of who I thought I was,” he sings in “Arizona”. It’s the first song he wrote months after his collapse, the first song on The Boxing Mirror, the album he didn’t think he’d live to record.

Produced by John Cale, The Boxing Mirror — released May 2 on Back Porch Records — teams Escovedo with one of his earliest and deepest musical inspirations. Cale’s viola work with the Velvet Underground represented a seminal attempt to combine the avant-garde dissonance of chamber strings with the chaotic surge of rock ‘n’ roll, a synthesis Escovedo has extended through his solo career.

After the Velvets disbanded, the work of Cale and Lou Reed continued to provide templates for Escovedo’s musical progression. And some of the classic albums produced by Cale — the Stooges’ debut (which included “I Wanna Be Your Dog”, still a string-driven staple of Escovedo’s live performances), Patti Smith’s Horses, Nico’s solo albums — rank with Escovedo’s favorites.

“He has more than he even knows to do with my music,” says Escovedo. “His Paris 1919 was totally influential on what I do now. It was probably like the blueprint, that and [Lou Reed’s] Street Hassle.”

In its emphasis on atmospherics and studio manipulation, The Boxing Mirror de-emphasizes the twangier, rootsier, rockier side of Escovedo’s music. Yet he’s plainly prouder of this album than of anything he’s ever done, at least partly because of all he went through to make it. The album is also a love letter to Kim Christoff, the woman who went through it with him, who became his wife and the mother of his 3-year-old daughter, Kiki. Her poetry became lyrics for three of the album’s songs. It was Christoff whose faith, determination and perseverance prevailed when Escovedo’s occasionally faltered.

The album had to start with “Arizona”, because that’s where Escovedo suffered what he thought was the worst thing that had ever happened to him. And now thinks was the best thing that could have happened to him.

“Arizona is where I collapsed, it’s where I met Kim, it’s where I recuperated,” he explains. “We were afraid, but we were strong, because we loved each other. And Kim was not going to let this happen. She was going to find some way, the best doctors or acupuncture or yoga or meditation or whatever.

“We spent a month out there after I finally got out of the hospital, and I walked in the desert and meditated and tried to figure out what was going to come out of all this….There wasn’t any sense that, oh, I’ll be OK in six months and I’ll go make a record or even play a gig.”

“Have another drink on me,” he sings, with an edge in his voice that’s more like a challenge than an invitation. “I’ve been empty since Arizona….You say I’ve lost my way, but it’s all a dream, since Arizona.”

“You get the sense that you don’t know who you are,” he explains. “Because everything had been created around this person who plays music. You make sure that the strings are ready to go, that you look sharp when you go out onstage and play. Night after night after night after night for 30 years. And suddenly you’re faced with, ‘Well, I don’t do this anymore.’ If I’m not the guy in front of the microphone, who am I?”

As the guy in front of the microphone, he’d already been moving toward a healthier temperance. He’d been diagnosed with hepatitis C in 1996, and he’d started to take better care of himself. More or less. He’d been eating better, drinking a lot less, particularly when he was scared because his energy was flagging or he was looking a little green. But then there’d be other nights, at the Hole in the Wall in Austin or on the road, where abstinence went out the window. Given the excesses of earlier years, he practiced moderation but not absolute denial.

“During that week in Arizona I might have had one Tecate,” he remembers. “I was smoking pot, but I’d always smoked pot. I wasn’t being a drunk. I was being a father and trying to be the best mate I could to Kim. We were enjoying ourselves, but I didn’t have a bottle by my bedside. I wasn’t a saint, but I was trying, man.”

He recounts those hours before his rush to the emergency room in matter-of-fact detail, more like describing a movie than reliving a nightmare. “The night before, Kim and I went to dinner,” he continues. “It was a nice warm spring evening and we went for a walk. The next day, I felt really bad, very nauseous, intense flu symptoms. Not just that I’m a little hot or I’m a little queasy; I was sick. I went to the soundcheck and kind of crawled back to the hotel that was across from the auditorium.

“And I thought maybe it was the heat, that I wasn’t used to it. But then I got into my suit and felt a little better. Suits will do that for you. I got the ten-minute call, and suddenly I was throwing up blood in the toilet — two bowls full of blood. I was with Bobby Neuwirth [the songwriter who was best known in the 1960s and ’70s as Bob Dylan’s running buddy], and I could tell he was looking at me strange. He asked what was up, and I said I didn’t know. I wasn’t sure what it was.”

But the show must go on. The show in question was By The Hand Of The Father, a theatrical song cycle chronicling his father’s move from Mexico to the United States and the patriarchal legacy that would enrich his son’s music. The material was very much a labor of love for Escovedo, but it was also part of a shift toward a healthier life as a performer. Instead of late nights in smoky bars with rounds of drinks, he’d be playing comfortable theaters where attention was focused and rapt. Writing for the theater, maybe even writing for films, might be a way of easing him away from that rock ‘n’ roll grind, the treadmill he’d once described in song as “more miles than money.”

“So I went onstage and did the whole performance,” he remembers. “It was bizarre, surreal. Then I rushed off and was rushed to the emergency room, where I realized what was going on. I had internal bleeding in three spots. The veins in my esophagus had burst, I had advanced cirrhosis of the liver and a tumor in the abdomen. They were all bleeding.

“The first nurse I had was this perky, blond sorority girl who bounces in and says, ‘Do you know why you’re here?’ And I said, ‘Yeah.’ And she goes, ‘Well, you don’t have that long to live. You better get on a liver transplant list.’ Then there was this other nurse who goes, ‘Why are you here?’ And I said, ‘Hep C.’ And she said, ‘Well I had it too,’ and she started speaking in this conspiratorial whisper, ‘You know how I got rid of mine? I drink my urine every morning.’

“And I go, Man, am I in the psychiatric ward?”

“I died a little today,” Escovedo sings on one of the new album’s key tracks, with perhaps the warmest, most supple and heart-aching vocal he has ever recorded. “I put up a fight, and carved a simple hello, you can hold to the light…Gonna learn how to give, not to simply get by, or to barely hang on, for the sake of goodbye.”

“There’s always been introspection in his songs, and that’s what I love about his songwriting, but now it’s on a much deeper level,” says drummer Hector Munoz, whose musical relationship with Escovedo spans two decades, since the latter days of the True Believers. “I mean, the guy was close to death. And when someone thinks about what they’ve been through and how close they were to leaving, there’s a lot of catharsis going on, on a very loving and spiritual level.”

Musically, Escovedo feels that The Boxing Mirror is what he’s been working toward ever since the early days of the Alejandro Escovedo Orchestra, which evolved as less a band than a workshop or a collective, a dramatic departure from the three-guitar rampage of the True Believers. The commercial failure of the Troobs, a band that had once seemed destined for rock greatness, left everyone involved drained, disillusioned and bitterly disappointed.

“Whatever anyone says, at the time it was the best damn rock ‘n’ roll band in America,” insists guitarist Jon Dee Graham, Escovedo’s bandmate then and now. “We toured nonstop once for nine months, in a van, not a bus or an airplane, and it was very intense. And when something that you’re so deeply invested in blows up, there’s gonna be debris.”

Once Escovedo found the energy to pick up the pieces, he expanded his music to include a lot of influences that didn’t seem like they fit together. There were the big bands of his older brothers Pete and Coke, both percussionists in California. (Coke’s passing in 1986 seems all too familiar now: He died from internal bleeding after a hospital stay involving a tumor after a life of having “thoroughly enjoyed himself, kind of in excess,” Escovedo noted in a 1998 interview with No Depression.)

There was also the Austin version of Ronnie Lane’s Slim Chance, an eclectic band of acoustic gypsies, with Escovedo among the musicians who backed the former Faces member after Lane moved to Texas, suffering from multiple sclerosis. There was the music of the Velvets, and of solo Reed and Cale. And there were the ambient soundscapes of Brian Eno (the visionary producer and former member of Roxy Music who would subsequently collaborate with Cale).

“The space around you is what kind of shapes you,” says Escovedo. “I wanted to do something like Eno’s Another Green World, but with a southwestern flavor. I mean, you watched the orchestra grow up, from when it was just J.D. [Foster, the True Believers’ bassist in their later stages and more recently an accomplished producer], Chris [Knight, an atmospheric keyboardist] and I. Then it became a workshop. I had been touring so much with the True Believers, and the Orchestra wasn’t going anywhere. There were just too many people.

“We had all those jazz players, we had all those percussionists, we had Danny Barnes and Mark Rubin [soon to be Bad Livers], we had Spot, Lisa Mednick, Rick Poss — just an amazing group of musicians. Why go anywhere? We weren’t making any money, but we were having wonderful shows.”

The Orchestra served to recast and renew — even reinvent — Escovedo’s music on a nightly basis. In the early 1990s, it wasn’t unusual to see him playing around Austin more than a dozen nights a month. You never knew which musicians would show up, which direction the music might take; one night it could sound like a mariachi or a chamber ensemble, another night like Van Morrison’s Band & Street Choir, or at the outer fringes like Sun Ra’s Arkestra. It could surprise and soar like no other band, or it could collapse into chaos — a thrilling chaos. (The rest of the world got glimpses once a year, when an extended Orchestra lineup delivered a traditional Sunday-night South By Southwest closing show at La Zona Rosa every March.)

Like the songs of Neil Young, Escovedo’s material plumbed complex emotional depths with folk-like simplicity, in a manner that held their strength whether they were supported by the lilt of a string section or savaged by his hard-rocking side band, Buick MacKane (named for the T. Rex song and sounding like the True Believers’ drunker, younger brothers). The music never solidified into a product; it was always in the process of becoming. Fluid, not fixed.

When the time came to record Escovedo’s solo debut, 1992’s Gravity, something other than the occasionally sloppy serendipity of the Orchestra was deemed necessary. Spontaneous combustion that sounds so exciting in live performance can be a mess in the studio. Escovedo sought the outside ears and musical focus he needed from Stephen Bruton, long the guitarist for Kris Kristofferson and Bonnie Raitt, and the producer of Jimmie Dale Gilmore’s breakthrough After Awhile.

A strong hand in the studio, Bruton selected the musicians and much of the material. He brought in players with more studio experience in place of most of the Orchestra members, and he decided not to include “Thirteen Years”, which had been a highlight of Escovedo’s live performances, because he thought it sounded too much like the Eagles. (It would subsequently become the title song of Escovedo’s second Bruton-produced album, in a slowed-down, chamber-string arrangement.)

“The songs were still sketches of what Al wanted to do, until Bruton saw what he could do with them,” says drummer Munoz, who didn’t play on the album. “I don’t think there’s ever been another band like the Orchestra. Even though the album wasn’t close to what the Orchestra was, it took elements from that, without the texture and the muscle that the Orchestra had. I was disappointed that we didn’t get to capture that; a lot of the people in the Orchestra were disappointed.”

It was hard to argue with the results, as Bruton and band streamlined the arrangements to put the attention on the songs rather than the intensity of the playing behind them. The album gave Escovedo a national presence as a solo artist, an artistic identity distinct from his earlier days in the punk-rocking Nuns, the cowpunk Rank And File, and the guitar-blazing True Believers. Thirteen Years followed in 1993 before Escovedo moved from local label Watermelon to major indie Rykodisc for 1996’s With These Hands.

After three albums with Bruton that extended the aural palette, Escovedo seemed to emphasize his rockier, roadhouse side when he signed with Bloodshot, Chicago’s “insurgent country” imprint, where labelmates such as Jon Langford and Kelly Hogan surrounded him with kindred spirits. Chicago had become arguably Escovedo’s best market outside Texas, and Bloodshot promoted him as a flagship artist.

After 1998’s well-received live album More Miles Than Money, and the following year’s Bourbonitis Blues, a grab-bag of originals and covers (including material by John Cale and Lou Reed), he rallied with 2001’s A Man Under The Influence. Produced by Chris Stamey in North Carolina and featuring musical support from the Carolina alt-country community, it was hailed by many as Escovedo’s best ever, or at least his best since Gravity.

Some of the album’s highlights had been written for By The Hand Of The Father, the theatrical project that would command most of Escovedo’s attention for the next couple of years. Once that stage tour had ended, the plan was for Escovedo to make his next album for Bloodshot with Stamey again producing.

And then Escovedo collapsed. And everything changed.

“We’d done these demos — ‘Dearhead’, ‘Looking For Love’ and ‘Break This Time’,” says Escovedo. “And then I got sick, didn’t play a guitar for a long time. And I remember Chris was one of the few people that I spoke to during that time, early on, as the whole treatment was beginning. And he said, ‘You know, it doesn’t matter who produces your next record or anything. Just make the record you’ve always dreamed of making.

“And it took me a long time to get there. The Bloodshot affair just ran its course, I think. They’re wonderful people, I have no hard feelings, but it was time to move on. I don’t like to stay in one place for too long.”

Thus, the new album is Escovedo’s first for Back Porch, an Americana imprint with major-label distribution, where his labelmates includes fellow Texans Charlie Sexton, Flaco Jimenez and Freddy Fender. The personal connection with producer Cale, whose music Escovedo had so long admired, came through their mutual friendship with Sterling Morrison, the Velvet Underground guitarist who’d moved to Austin (to teach English at the University of Texas) after that band’s demise.

At the Austin Music Awards in 2001, both Cale and Escovedo participated in a belated tribute to Morrison (who had died in 1995). Four years later, they reunited for a collaborative performance at the awards show, held every year at the start of the South By Southwest festival. In the years between those two SXSW appearances, Escovedo had suffered his collapse and begun his recovery, his spirits bolstered by the generous support of fans and fellow musicians through an extensive benefit campaign dubbed Por Vida (For Life).

Clubs across the country hold shows in Escovedo’s honor, and many of his musical inspirations as well as members of his extended family participated in 2004’s two-disc Por Vida: A Tribute To The Songs Of Alejandro Escovedo. The proceeds subsidized the medical expenses of a musician with no insurance and (at least for a couple of years) no livelihood. Escovedo’s manager Heinz Geissler estimates the initiative raised $100,000 in the artist’s behalf.

The effort also let him know just how much his music had meant to those whose music had meant so much to him. Many of the album’s performers subsequently gathered for a tribute concert to Escovedo, capped by his return to the stage.

“It was kind of like attending your own funeral,” he says with a laugh. “Not many people get to hear what other people think about them — at least not in such a nice way. And I made a lot of good friends out of that. I mean, shoot, Ian Hunter [of Mott The Hoople, and oft-covered by Escovedo] sang one of my songs — and it was like Mott! John Cale sang one of my songs, and it was genius. Ian McLagan [another Faces transplant to Austin], Jennifer Warnes, Lenny Kaye for god’s sake!

“Looking at that record, it was like everything that had ever impressed me, a family tree of my musical influences. And it would pretty much cover my record collection. I can’t begin to tell you how great it made me feel, and how humbled. Listening to it, I literally would break down and cry.”

Among the dozens of artists contributing to the project were Alejandro’s brother Javier Escovedo and Jon Dee Graham, the other members of the True Believers’ guitar triumvirate. After that band broke up, Graham and Alejandro had barely spoken for more than six years, until 1994’s Hard Road reissue and some True Believers reunion dates brought them back together again briefly.

Escovedo’s illness showed that life’s too short to let minor squabbles destroy a musical partnership with major benefits for both of them. Upon resuming his career in 2005, Escovedo enlisted Graham as lead guitarist for both touring and recording.

“Jon Dee and I had separated after the True Believers for a reason so silly I can’t even tell you,” says Escovedo. “But after I got sick, I really wanted to forget all that stuff. And I thought, who’s the best guitar player I know who understands what I’m doing? So I asked Jon, and he said yes. And I remember seeing him on that side of the stage forever, and it’s great to hear that kind of guitar playing around me and just to be around him again. My only doubts is that this can’t last forever, because he has his own career.”

“I will play with him as long as is humanly possible,” says Graham, who’ll balance his band work with the spring release of Full, his latest solo album, on Freedom Records. “It’s a big wide river, and there’s a lot of water that has passed under that bridge. The whole time we were in the Believers, he and I were roommates when we would tour, so we were pretty tight. And then there was this long period where we weren’t so tight.

“But pretty much from the time we’ve gotten back together, there’s this chemistry still. I’m a different man now, and he’s a different man. We’ve been through all these things separately. But musically I think we still read each other’s minds a little bit. And it’s just so much fun playing together.”

The respect Escovedo receives from those who have played with him longest seems to apply simultaneously to his music and his character, as if the two are inextricably intertwined. They see him as a great artist, but, as important, as a good friend. And they recognize that there have been some changes in his character since his illness that have enriched his music.

“There’s different currents that flow through the man,” Graham says. “He’s still Al. He’s still wicked funny. But there’s a peaceful air about him now, a calmness that I don’t think I ever saw in him before. And I don’t know what that is. Because I could see fear, I could see determination, I could see all that stuff, but what I’m seeing instead is calm.”

“This is a grown-up band, with grown-ups playing,” says Munoz, who teams with veteran bassist Mark Andes [Spirit, Jo Jo Gunne, Heart] as the album’s rhythm section. “Everybody listens to each other, and I think everybody’s really respectful and appreciative of everyone’s musicianship. And we’re performing our best every night, because the alcohol doesn’t come into play, or any of that other stuff we thought we needed to make us play better or make us laugh.”

Says violinist Susan Voelz, who has split time between Escovedo’s bands and Poi Dog Pondering for more than a decade (and who also played with him in Ronnie Lane’s Slim Chance), “We have the freedom to play our very best and then some. He trusts us to do that, and he trusts the songs, that they can do that. It’s like he’s saying, Where can you take it? What do you got? What do you got? No, deeper! What do you got? Even onstage, I don’t know if the audience can hear him, but it’s like, Go! Give it! He really pushes you to reach and go somewhere where you don’t know what might happen next.”

Such spontaneous combustion ignited the album launch for The Boxing Mirror in mid-March during South By Southwest at Las Manitas, a storefront Mexican restaurant that is like a musical home and good-luck talisman for Escovedo. As perhaps a hundred invitees feasted on tacos and tamales in the intimate back room, the acoustic septet (sans Graham) put an electric charge into material that many in attendance had yet to hear, while familiar fare such as “Put You Down” seemed to soar with the strings as rocket fuel. As the material took off, the musicians appeared as excited as the audience to hear where it might go.

The chances Escovedo takes with his music and the risks he demands are evident throughout the new album. Just as Escovedo challenges musicians and pushes them beyond their comfort level, he hoped for the same from producer Cale.

“I knew that we wanted to get more into the sampling and stuff we’ve been doing onstage,” he says. “I wanted it to be a little more atmospheric. But at this point I know that when you go in to make a record, you can’t really determine what it’s going to be about. Because so many things go into play, especially with John. And that’s the beauty of making records, the surprises that happen in the studio.

“So I kinda let John produce the record. Before I left [to make the album], Joe Nick [Patoski, former True Believers manager, No Depression contributing editor, and Escovedo’s Wimberley neighbor] said, ‘Ask him if there’s anything he’s never done that he’s always wanted to do in the studio. And then ask yourself if there’s anything you’ve always wanted to do. Be open to all the possibilities.”

The results push all sorts of envelopes. (Patoski later told me that a musician friend, on first hearing it, said it sounded like Pink Floyd.) Where so many previous Escovedo recordings approximate the arrangements of a live performance, here there are strings that sound like keyboards, percussion that sounds programmed, guitars that erupt out of nowhere.

There’s a jittery remake of “Sacramento & Polk” that takes it to an edgier place than the original on 1999’s Bourbonitis Blues. There are two different mixes of “Take Your Place”: an alternate mix that places it within the familiar Stones/Faces tradition, and a Cale deconstruction that sounds to this listener like Prince (it drew mixed response from the band).

“Both Cale and I liked the Stonesy version OK,” Escovedo says, “but I said, ‘You know, I’ve done this [kind of] song several times before, and the Stones don’t really need my advertising anymore. They’re doing OK without my waving their flag. So he spent a whole day working on it — it’s just groove and vocals, and that’s all there is. It repulses some of the band members — one of them said it sounds like Haircut 100 — but I just love that it’s different.”

Whether because of Cale or the circumstances preceding the sessions, Escovedo has never sung with more warmth and open-hearted vulnerability. Particularly on “I Died A Little Today”, “The Ladder” (a cantina-flavored love song for Christoff), and “Evita’s Lullaby” (written for his mother), he achieves a tenderness on the ballads that extends the interpretive range of his vocals.

“I wrote that for my mom after my father passed away,” says Escovedo, who’d felt as if he was punched in the gut by death all over again when his dad passed two years ago, in the midst of his son’s convalescence. “He knew he was going to die, and he was very much at peace with it. But we were all just crushed. Here I read Buddhist philosophy, scripture, and I think I have this sense that everything moves on, there’s a cycle, and we have many lives that we pass through, and everything’s connected and all that.

“But when it happened, all that went out the window. I was lost, man. I really was. I went to the memorial in San Diego thinking that I was going to say something about my dad. I couldn’t open my mouth. I look at pictures of me there, and I look like I’m older than my mother.

“So I wanted to write this song that would be me talking to my father about my mom, how much I remember them dancing, and how much I know she loved him. And how I hope they’re together soon in a peaceful way.”

For all of the pain reflected in the material Escovedo wrote for The Boxing Mirror, there’s a profound peacefulness there as well. The closer he came to death, the richer and deeper his appreciation for life became. Whether or not it’s his best album, as he believes, it’s certainly his bravest, in the chances it takes both musically and lyrically. And it’s plainly the one that means the most to him.

“This album to me sounds very confident. It sounds strong. One of Cale’s main objectives is that it should sound like someone who isn’t sick anymore,” Escovedo says.

“You know, I shouldn’t say this, but I was scared of dying. I’m not frightened of death anymore, because I confronted it. I faced it, and I know what death feels like. And it’s not a bad thing. Not a negative thing. It’s just part of life.”

When ND senior editor Don McLeese lived in Austin, he and Alejandro Escovedo would meet for Mexican breakfasts and spend more time talking about baseball, books and daughters than music.