Culture and Struggle

In July of 1959, armed officials raided the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, during the final night of a weeklong leadership workshop for black and white participants of the burgeoning civil rights movement. They cut off the lights for nearly two hours, searched the building, assaulted some of those present, and carted others off to jail. Neither the workshop nor the raid was unusual. Since its founding during the Depression by Myles Horton, the son of a white sharecropping family, Highlander had been a hub for multiracial and intergenerational groups of Southern organizers. It had always operated under threat from state authorities and the Ku Klux Klan. The fact that the intrusion was not unusual, however, did not make it any less frightening, and while nonviolence countered the tactics of the raid, song combatted the fear.

One among those huddled in the dark began humming “We Shall Overcome.” Others joined in, and then Mary Ethel Dozier, a black high school student from Alabama, invented the now-familiar lines, “We are not afraid. We are not afraid. We are not afraid today.” Dozier’s improvised verse was taken up by the rest of the group, and the song reclaimed space and galvanized spirits until the end of the raid.

At this point in time, “We Shall Overcome” had been sung regularly at Highlander for years, but had yet to become the anthem of the civil rights movement. Most of those in attendance had likely just learned the song from Guy Carawan and Septima Clark, Highlander’s white music director and black education director. The two had been collaborating for months to support traditional black singing on the movement’s front lines by incorporating Carawan’s song-leading into Clark’s trainings throughout the South.

Carawan and Clark both missed that night’s singing, however, as they had been among the first to be arrested and were already on their way to jail — an experience that threw their differently racialized relationships to power into stark relief. As the arresting officer took roundabout routes along dark roads and switched cars to avoid being followed, Carawan demanded to know their rights, but Clark, fearing for her life, desperately urged him to keep quiet. While the interracial group they had left behind asserted unity in song, Clark and Carawan found themselves very much at odds.

From ‘I’ to ‘We’

The musical history of “We Shall Overcome” is rooted in traditions of black cultural resistance, but its social history — the experiences of those shaping its use — tells of the triumphs and struggles of cross-racial coalition-building. Dozier’s impromptu transformation of fear into sung resistance drew on her background in the black congregational church and experiences as both a participant in the Montgomery bus boycott and member of the Montgomery Gospel Trio, the boycott’s core song-leading body.

The song she sang that night in 1959, however, was not a traditional black song but a strategic revision crafted for political use by black and white cultural organizers. As Highlander-affiliated activist and song-leader Wendi O’Neal says, “The song [marks] the freedom movement as a desegregated moment. A moment when black and white were singing together. When we started to say ‘we’ and not ‘I.’”

There are tensions inherent in this move from “I” to “we” — tensions highlighted by Carawan and Clark’s ride to the police station that night, and extending into contemporary debates about how best to narrate the song’s interracial history and legacy. But facilitating such charged engagements across difference is the life’s work of “We Shall Overcome.” It evokes ongoing determination and, as scholar and civil rights-era song-leader — and founder of Sweet Honey in the Rock — Bernice Johnson Reagon says, “if you feel the strain you may be doing some good work.” Recovering the struggles and strategies of those who shepherded the song to prominence reveals that “We Shall Overcome” is not simply a brilliant anthem; it is the result of brilliant organizing.

From Church to Frontlines

“We Shall Overcome” originated in black spiritual and gospel traditions and was transformed from church hymn to protest anthem by black women of the Southern labor movement. It is a melodic descendant of turn-of-the-century gospel standard “I’ll Be Alright” and a lyrical descendant of “I’ll Overcome Someday,” a spiritual copyrighted in 1900 and credited to the popular Philadelphia minister Charles Albert Tindley.

In 1945 Lucille Simmons and other black women workers of the integrated Food, Tobacco and Agricultural Workers’ Union of America (FTA-CIO) Local 15 brought it to their five-month strike of a Charleston, South Carolina, cigar factory. Their picket line sound reflected the local’s overwhelmingly black and female membership and resonated with other music emerging from the increasingly integrated unionism of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Emphasizing the song’s call for fierce determination and its “prayer of relief,” as picketer Lillie Mae Marsh Doster described it, the Charleston workers performed a slow-paced version from nearby Johns Island — one that stretched the refrain “I’ll Overcome” into “I Will Overcome.” They changed the “I” to “We” to better reflect the collective voice of the integrated union and, with added verses such as “we will win our rights” and “we will organize,” it quickly become the theme song of the strike.

Two years later, “We Will Overcome” was brought to Highlander. Workers from Charleston’s Local 15 shared it in a workshop led by Zilphia Horton, the white director of Highlander’s cultural arm and wife of its founder, Myles Horton. Zilphia had formalized an extensive set of cultural programs in support of the labor movement, including publishing personal narratives, producing worker’s theater, and collecting and disseminating traditional music. Her tireless efforts and nuanced understanding of the organizing potential of song led Highlander to be nationally recognized by the unions as the “singing labor school.” Upon hearing “We Will Overcome,” she was instantly taken by its power and began featuring it in her trainings and picket line songbooks.

After becoming part of Highlander’s repertoire, the song underwent a series of revisions, mostly by white folksingers. As Myles Horton later reflected, “it probably developed independently where it came from, but it had its own life at Highlander.”

Early on, Zilphia Horton gave it an Appalachian rhythmic style befitting her accompaniment on the accordion and eventually taught it to her friend Pete Seeger. Seeger sang it around the country, gave it a more rigid rhythmic structure and added the verses “the whole wide world around” and “we’ll walk hand in hand.” Seeger is often credited with changing the “will” in the song’s refrain to “shall” but he recalled in a 2004 interview that Septima Clark also felt “shall” “opened up the mouth better than ‘will.’”

“We Shall Overcome” welcomed and inspired a new cadre of organizers in the early 1950s as Highlander shifted its focus from worker’s rights to racial violence and segregation. Seeger sang his version at Highlander’s 25th anniversary gathering in 1957, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. — who attended with Rosa Parks — heard it for the first time. Days later, King remarked, “There’s something about that song that haunts you.”

The Power of Black Song

Zilphia Horton died in an accident in 1956, and three years later California-born folksinger Guy Carawan succeeded her as Highlander’s musical director. Carawan had been passionate about radical change since his college years but was moved to action after hearing King speak alongside a powerful choir in a black Boston church. He called Myles, who he had known for some time, to see how he might support the movement. After three mournful years without Zilphia, Myles recognized the need to fill her shoes, and by the end of their conversation Carawan was packing his bags for Tennessee.

Carawan arrived with extensive knowledge of international folk songs and their political uses, graduate training in folklore, two successful solo albums, familiarity with Zilphia’s work, and mentorship from Pete Seeger, Lee Hayes, and Alan Lomax. He had learned “We Shall Overcome” from his California singing partner Frank Hamilton, who had added his own chord progressions on the guitar. Although an experienced folksinger and folk song scholar, Carawan did not have a sophisticated understanding of the structures and lived realities of the Jim Crow South or the nuances of the burgeoning desegregation movement he was about to join. As he would later recall of his arrival at Highlander, which had already become a leading hub for civil rights organizers, “I was still a babe in the woods.”

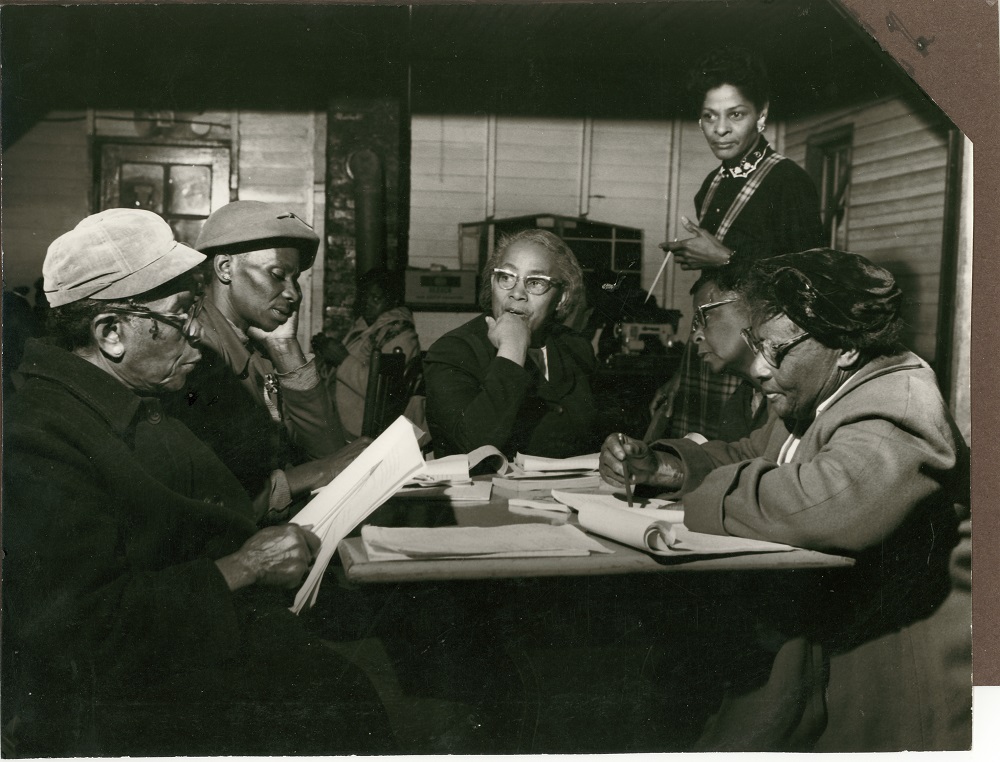

His education came fast and furious from the extraordinary black organizers with whom he found himself working. In his first months at Highlander, he led songs for residential workshops on “Integration and Citizenship” facilitated by Septima Clark — whom King later called the “mother of the movement” — and at gatherings across the South of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Captivated by Clark’s leadership and craving immersion in the folk culture of the black South, Carawan spent that winter working as her driver on Johns Island.

He led “singing schools” for the adult literacy and citizenship education program Clark, her cousin Bernice Robinson, and organizer Esau Jenkins were in the process of developing. The shock of seeing a Northern white man working as a Southern black woman’s driver gave way to suspicion for many elder islanders as Carawan’s approach to song-leading clashed with their own. Carawan adjusted his approach, and his “singing schools” grew to successfully bolster organizing efforts on the island.

In addition to shaping Carawan’s own song-leading, the collaborations he witnessed and supported that winter among Clark, Jenkins, Robinson, and Johns Islanders changed the face of the civil rights movement. Their Citizenship Schools spread throughout the Sea Islands, were replicated across the Deep South, and ultimately yielded hundreds of community teachers, nearly 100,000 newly literate Southern blacks and 42,100 voters.

The mentorship Carawan received that winter was invaluable, but seeing the inextricable link between island organizing and black congregational singing was transformative. As Carawan would later write, “that experience really changed my life.”

The night Carawan arrived on Johns Island, Esau Jenkins took him to an all-night service at the island’s praise house, Moving Star Hall. Carawan was familiar with more hierarchical church services and was surprised by the community-led gathering he witnessed at the praise house. Each person had the opportunity to lead prayer, offer testimony, preach, or raise a song. Carawan was awed by what he described as the “true spirit of community ownership” in Moving Star Hall and described it as “the most moving and democratic form of worship [he’d] ever encountered.”

More than just a worship service with extraordinary music, the hall embodied the values of democratic leadership cultivated by the likes of Clark, Jenkins, Ella Baker, and Myles Horton — values that countered reliance on the hierarchy of charismatic leadership from above by investing in grassroots, community leadership from below. The music, Carawan learned, was not simply an organizing tactic but the embodiment of organizing principles. That first night with Esau Jenkins, Carawan realized he had joined a remarkable organizing campaign whose leaders understood, more deeply than he, the important role of and lessons inherent in black culture.

“I recognized that something very special was taking place in that hall and in that community,” he wrote in a 1995 article co-written with his wife, Candie. “Here was the richness of an incredible African-American heritage and a courageous campaign to participate in the modern and changing world by gaining literacy skills and becoming registered voters. Esau Jenkins was the rare kind of grassroots community leader who understood both the value and beauty of the older folk culture and the necessity to fight for progress and change.”

Among the songs Carawan learned anew from Johns Islanders were “We Shall Not Be Moved,” “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize,” and the parent song of the movement’s soon-to-be anthem, “I Will Overcome.” Despite his extensive studies of folk music and travels across the country and the world, Carawan’s Johns Island experience stood out. He wrote during that winter trip, “I’ve never heard singing mean so much to people as it does to them.”

L to R from center: Septima Clark, Alice Wine, and Bernice Robinson meet with Johns Islanders.

Rise and Remaking

Carawan returned to Highlander at the beginning of 1960 having learned three things: the organizing power of black song, a refined method for teaching songs and song-leading skills, and a musical repertoire tailored specifically to the civil rights movement and prominently featuring “We Shall Overcome.” The traditional acapella “I Will Overcome” he had learned on Johns Island would have been more appropriate for the black freedom movement, but by 1960 Zilphia Horton and Pete Seeger’s “We Shall Overcome” had been featured and taught at Highlander for over a decade, and its rhythmic patterns, forged by folksingers with backgrounds closer to Carawan’s, better suited his musical style.

Within six months, he had taught this version to students of the Nashville sit-ins and to activists at three catalytic gatherings: Highlander’s annual weekend-long college workshop in early April, Ella Baker’s inaugural meeting of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) two weeks later, and a weeklong “Sing for Freedom” co-hosted with Septima Clark in August and advertised as Highlander’s “first musical workshop.” The song’s power was instantly felt while being sung at SNCC’s founding meeting, and its signature stance — arms crossed right over left — was spontaneously born.

As the song spread throughout the movement, it received another series of revisions. During the 1961 Freedom Rides, new verses were developed on buses and in jails. Later that year and into the next, black song leaders on the front lines of SNCC’s campaign in Albany, Georgia, reinserted black congregational rhythms and improvisation that had been flattened or erased by Carawan’s strumming style on the guitar and banjo.

As Reagon remembers, Albany is where the song was “delivered back into the full range of expression of the black choral tradition.”

Years later, Carawan remembered Reagon, a Georgia native and leader of the Albany movement, interrupting his teaching of “We Shall Overcome” by saying, “lay that guitar down, boy!” Once his guitar was no longer guiding the singing, his even pulse and chord progressions were changed into a triplet rhythm and harmony more consistent with the a capella sound of the black church.

Albany’s Cordell Reagon, Rutha Mae Harris, and Charles Neblett joined Bernice Reagon as the movement’s song leaders. They became known as the Freedom Singers and toured the country as the education and fundraising arm of SNCC. They and other young activists sang “We Shall Overcome” throughout the South, folksingers popularized it on stages across the North, and televised protests and concerts brought it to living rooms nationwide. The song quickly became, as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., would later call it, “the battle hymn of our movement.”

All Rights Reserved

The song’s overwhelming popularity led Carawan, Seeger, and Horton to copyright it in 1960 — a controversial move Seeger later described as a “defensive” one intended to protect the song from cooptation and commodification. In Seeger’s memoir he remembered his manager, Harold Leventhal, saying, “Pete, if you don’t copyright this song, some Hollywood character will. He’ll put new lyrics to it like, ‘Baby, let’s you and me overcome tonight.’” Reagon remembers Seeger wanting the copyright to reflect its authorship “by American Negro people,” but copyright law requires attribution to specific individuals — an importation from European laws designed to protect classical music’s singular composers and written scores rather than oral tradition’s alternative notions of authorship and ownership. It was decided the copyright would read: “Musical and lyrical adaptation by Zilphia Horton, Frank Hamilton, Guy Carawan, & Pete Seeger. Inspired by African American Gospel Singing, members of the Food & Tobacco Workers Union, Charleston, SC & the Southern civil rights movement.” Seeger’s wife, Toshi, set up the copyright with Pete’s publisher, The Richmond Organization (TRO), and founding partner Al Brackman handled all requests for the song. Brackman’s charge, as outlined in extended exchanges with those named on the copyright, was to protect the song’s legacy rather than maximize its profits. All requests for its use in commercials or other circumstances thought to compromise its integrity were — and continue to be — routinely denied. Guidance from Reagon and Vincent Harding, a black theologian and colleague of King, ensured all royalties received from approved uses were put into a “Freedom Fund” exclusively for the black freedom movement. In 1963, the following sentence was added to the copyright text: “Royalties derived from this song are being contributed to The Freedom Movement under the trusteeship of the Writers.”

In addition to being integral to the song’s civil rights-era life, Reagon has also been a leading force in the rigorous and sometimes quite contentious oversight of the copyright. Brackman consulted her whenever he was unsure about a request — a practice passed on to his successor, Larry Richmond, and continued to this day — and Carawan, Hamilton, and Horton followed guidance from her and Harding on how best to disseminate royalties. It was under her leadership that funding parameters were redefined to specify that grants would go to exclusively to black-led cultural organizing projects in and for the black South. She also codified practices to publicize the fund and oversaw much of the training grant recipients received.

In 1965, management of the copyright was signed over to Highlander. The We Shall Overcome Fund, described as a “living memorial” to the song, was established as a repository for royalties and resource for activists working at the intersection of “culture and struggle.” An advisory committee was established to publicize the Fund, evaluate received proposals, and make granting recommendations to Highlander’s board. Reagon was a founding member of this committee and represented cultural workers of the civil rights movement along with Harding. The committee also included Dorothy Cotton representing SCLC, Faye Bellamy representing SNCC, and Carawan, with the support of his collaborator and wife, Candie, representing Highlander. Harding, who had decided that his peace-making work was best served by a sole organizational affiliation with the church, soon left the committee. The remaining founding members worked tirelessly — and sometimes through great conflict — to protect the song’s legacy and shepherd its continued work.

To some, the copyright and its control by two white-led institutions — TRO and Highlander — feel like an affront to the spirit and history of black freedom singing. Throughout the copyright’s 56 years, this arrangement has sparked conflict among insiders and critique from outsiders. The white names on the copyright threaten to eclipse the song’s black history, and oversight by the Highlander board compromises the Fund’s independence. The most public critique came in April 2016, when a lawsuit was filed against TRO describing the copyright as both “unlawful” and “wrongful.” The suit is frequently described in almost entirely sympathetic media as endeavoring to “liberate” the song to the public domain. Yet despite ongoing struggles, the Fund has supported decades of organizing and scaffolded a number of contemporary movements. Although it does not resolve larger questions about how or if the law should have a role in regulating traditional culture, the Fund stands as a pioneering effort to navigate this complex terrain. Flying in the face of European-descended copyright laws ill-suited to protect traditional black music and the cultural values it embodies, the Fund rewrites notions of legal ownership and reward and has supported hundreds of Southern black cultural workers. Reagon, who has been on the frontlines of the Fund’s struggles and triumphs for 56 years, has called it “one of the most amazing copyright structures” in our nation’s history.

Recovering Hidden Histories

Histories of “We Shall Overcome,” like those of the civil rights movement, frequently suffer from distorting oversimplifications. Investment in bracketed timeframes erases histories of sustained struggle. Focus on charismatic leaders eclipses the work of grassroots organizers. Celebration of white allies prematurely curtails understanding of black organizing. And reliance on the written record ignores those without privileged access to the archive.

The work of Zilphia and Myles Horton, Pete Seeger, and Guy Carawan was invaluable, and they leveraged their privileged access — to audiences, funds, publishers, travel, and time — to powerfully bolster the song’s trajectory. Nonetheless, their work rests on the visionary efforts of under-recognized black cultural workers including: Lucille Simmons and the black women of the Charleston FTA-CIO; Septima Clark, Esau Jenkins, Bernice Robinson, and Johns Islanders of the Citizenship Schools; and SNCC’s Freedom Singers Cordell Reagon, Bernice Johnson Reagon, Rutha Mae Harris, Charles Neblett, and others of the Albany movement. Further, Reagon, Vincent Harding, Faye Bellamy, and Dorothy Cotton indelibly shaped the song’s continued political use as founding members of the We Shall Overcome Fund, and a new generation of guardians has succeeded them. Tufara Muhammad served as the Fund’s outreach worker and Highlander’s cultural organizer from 2004 to 2015, and Omari Fox, Ebony Golden, Wendi O’Neal, and Carlton Turner currently lead the advisory committee.

As the song continues to be leveraged in movements for change — most recently in the wake of the Orlando massacre and in response to the continued deaths of black people at the hands of police — the organizing history of “We Shall Overcome” and the commitment of this lineage of cultural workers deepens our understanding of what it means to sing for freedom.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2016/Speak Up issue of No Depression in print. Purchase a copy of that back issue or subscribe today and don’t miss another issue of our quarterly journal.