Bob and the Band at the Brickyards: Bringing It All Back Home

Bob Dylan first headed up the Hudson River to Ulster County, New York, almost 55 years ago. After Albert Grossman became his manager, in mid-1962, Dylan regularly skipped out of Manhattan to visit Grossman and his wife, Sally, in Bearsville. The sign on Route 212 in Bearsville says it was named not for the black bears still plentiful in the surrounding Catskills, but for a Mr. Baehr, who had a store there back in 1839, where the Sawkill Creek crosses the road. Dylan liked the area from Bearsville to Woodstock to Saugerties and Kingston — liked it so much that, when his early fast fame made New York and the concert roads both crazy places for him, he sought to come to rest there in 1965. Dylan, 24, and his new wife, Sara, 25, set out to raise their young family there. With two daughters and two sons soon filling the home (youngest son Jakob was born in 1969, after the Dylans had left Woodstock), and the members of his most recent traveling band living in various houses, cottages, and mobile homes in the area, Dylan spent the days that would turn out to be, both personally and professionally, his most productive. Fellow musicians who were friends, like Happy Traum, lived in Woodstock, and were raising babies and toddlers the same age in the neighborhood. Richard Manuel, Rick Danko, and Garth Hudson had a big pink house with an unfinished basement heated by a wood stove in Saugerties, on the perfectly named Parnassus Road (oracles, Muses, Pegasus, Dionysus: remember your mythology?). From 1965 through the summer of love in 1969, Woodstock was home for the Dylans. Ironically, the music festival that was moved 60 miles southwest, down to Bethel and Max Yasgur’s dairy farm, to spare the town of Woodstock itself helped to wreck that for the family.

Here is how Dylan remembers the end of his Woodstock days in his memoir Chronicles Vol. 1 (2004):

At one time the place had been a quiet refuge, but now, no more. Roadmaps to our homestead must have been posted in all fifty states for gangs of dropouts and druggies. Moochers showed up from as far away as California on pilgrimages. Goons were breaking into our place all hours of the night. At first, it was merely the nomadic homeless making illegal entry — seemed harmless enough, but then rogue radicals looking for the Prince of Protest began to arrive — unaccountable-looking characters, gargoyle-looking gals, scarecrows, stragglers looking to party, raid the pantry. … Not only that, but creeps thumping their boots across our roof could even take me to court if one of them fell off. This was so unsettling. I wanted to set fire to these people. … Each day and night was fraught with difficulties. Everything was wrong, the world was absurd. It was backing me into a corner.

* * *

I don’t know what everybody else was fantasizing about but what I was fantasizing about was a nine-to-five existence, a house on a tree-lined block with a white picket fence, pink roses in the backyard. That would have been nice. That was my deepest dream. After a while you learn that privacy is something you can sell, but you can’t buy it back. Woodstock had turned into a nightmare, a place of chaos.

Much has been written by others, and some of it good — like filmmaker David McDonald’s 2004 essay — on Dylan in Woodstock. He has returned to the area repeatedly since he left, however. Until an unspecified date, he continued to own Hi Lo Ha, the Dylans’ family home off Upper Byrdcliffe Road on the wide shoulder of Guardian Mountain. On his so-called Neverending Tour, since 1988, he has played regular shows up and down the Valley and west in the mountains; he and the band seem particularly partial to Poughkeepsie. In 2010, they delighted us with a golden performance of “This Wheel’s On Fire,” a song Dylan wrote in Woodstock with Rick Danko in 1967. Dylan and his band have rehearsed in the town’s Bardavon Opera House before tours, and, most recently, they were in Kingston, New York — just up the river and over from Poughkeepsie, and 20 minutes from Woodstock — for two shows at the Hutton Brickyards.

The Brickyards were just that for more than a century. In 1865, the Hutton Brick Works Company was founded just north of Kingston’s little sandy swimming beach on the west bank of the Hudson River. Since the 1980s, though, the kilns and sheds and sturdy brick office buildings sat silent, Virginia creeper and poison ivy moving quickly together over the coppery-russet mounds of bricks and iron building frameworks. Enter Karl Slovin, a Los Angeles-based property owner and developer and president of MWest Holdings. Slovin’s company specializes in, according to their manifesto, “acquiring properties in Los Angeles and around the U.S., seeking out architecturally rich and historic buildings that can be enhanced, restored and revitalized.” Slovin is a New Yorker, and his roots are in the Hudson Valley, in Rhinebeck. He set out to make of the old brickyards a place where local art, music, crafts, and food could be showcased and visitors could come and enjoy them. Last summer, good times were had thanks to Smorgasburg Upstate. This summer, the two long L-shaped main structures — cement-floored and open on all sides to the river that is only feet away — became the concert venue they absolutely and superbly are.

The first weekend of the summer season at the Brickyards, in the middle of May, featured music from local musicians, including the immensely talented Connor Kennedy, who, after having opened for The Gipsy Kings and The Waterboys last summer, is releasing his solo record Somewhere on July 15th, and heading to Japan and China in August with Donald Fagen and the Nightflyers. (Remember: musical roots run deeper than deep in the Catskills. Fagen, another longtime local musician, has been married since 1993 to Woodstock-born singer-songwriter and legendary beauty Libby Titus — whose daughter with Levon Helm, Amy Helm, recently released the stunning solo album Didn’t It Rain).

Connor Kennedy and his band, May 18, 2017 at the Hutton Brickyards

The weather was gorgeous, and the venue downright magical as night fell across the twisted factory metal and brick orange. I walked the four long strides from the cement floor to the riverbank and watched the Hudson water giving back the sunset. Slovin and his family were on hand to welcome guests on opening night. He showed me the buildings that will make beautiful spaces for wedding parties and guest artists, and pointed out to me the renovated brick rectangle with windows above, with a light-strung industrial space inside, and said, “that’s the green room for Dylan and the band.” I loved it. I wanted to hear a performance in that little venue, with about 40 other lucky souls.

The green room, unoccupied

A month later, I came back twice, with about 4,000 other lucky souls, for Bob Dylan’s two shows at the Brickyards. I include the larger number because quite a few people listened from boats in the river — crafts from sleek sailboats to little Lasers and rowboats, with people swimming off the back in the shallow riverbend before the gigs, in sweltering heat. It seemed sensible to pony up for the parking space, though I was a bit worried about getting out on a thin riverside back road after the show. One night, I hit the ground running right after the encore; and one night, I lingered and enjoyed the food and beer and good company — neither time did I sit in a traffic queue. Shuttles of all varieties pressed into service, from town buses to streetcar-style jitneys to little minibuses, ran people to the concerts from the Ulster Performing Arts Center in downtown Kingston (UPAC is a sister theater to the Bardavon). People rode bikes and walked, too.

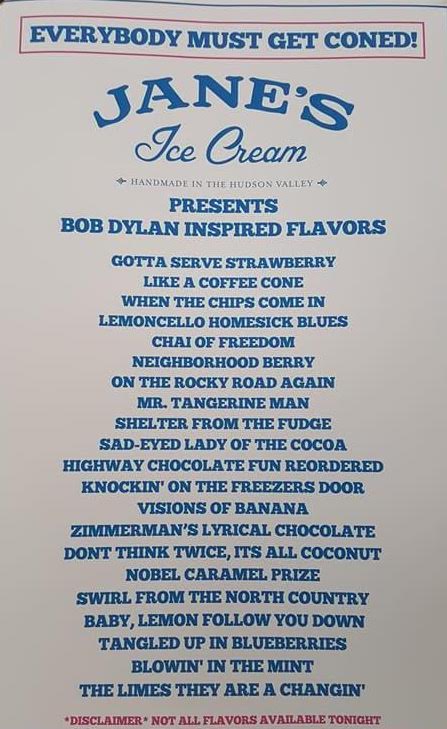

In the front row the first night were families: a father and son, around 70 and 40, who took turns getting food and posters and a Dylan baseball cap for each other. “He’s the fan,” the son explained. “I want this to be a great night for him.” Two women who could only have been a mother and daughter were at the ice cream line: both long-haired, in button-down shirts and slacks, smiling. “She taught me to listen to Bob,” said the daughter. “This is for her birthday.” The mother laughed. “I used to have beers with Bob when he lived up on Ohayo Mountain. He was a great, easygoing guy. But that Ford he drove, oh my. The dirtiest car I have ever seen.” The ice cream flavors, from the unmatchable Jane’s of Kingston, made people giggle and groan. “Sad Eyed Lady of the Chocolate” (alternately, “Cocoa”) was a total abdication of even trying to come up with a good name, I thought, but that’s what I got. It was delicious. And on such a night, everybody did indeed get coned.

Dylan and the band took the stage promptly, as is their custom, and from the first he seemed quite engaged. The absence of a hat was notable. Friday night, June 23rd, was stiflingly hot and humid, even on the riverbank — I was so overheated that part of the night seems still like a fever dream to me. But Dylan has long favored a hat or some sort of headgear on stage, from the sombreros and cowboy hats, to the do-rag days, and the cacophony of things he wore on his head during the Rolling Thunder Revue. Hatless, he looked startlingly young. I hadn’t realized how the brims of his hats not only hid his eyes in concert, but cast shade on his face so that you could really only see his neck and chin most of the time. With that silhouette of hair that has been part of the public image of “Bob Dylan” since the middle 1960s, and his face under the light — it was not nearly dark when the concert began — Dylan looked like, well, Dylan. His blue eyes scanned the crowd constantly, whether he was at center stage or sitting at the piano. Was he looking for a face in the crowd? Seeing past and present together? Enjoying the sight of the Hudson and the boats and clouds shining out there, past all the heads? He grinned as he performed “Don’t Think Twice,” and its follow-up, “Highway 61.” There, a couple of the old wonders. Now for something completely different. Dylan strutted to the microphone, grabbed it and spun it like a girl he was dancing with, and challenged us with the question “Why Try To Change Me Now?”

No one seemed to want to, either night. The American songbook standards that Dylan has recently recorded, and released now on three albums (the latest, and perhaps last, Triplicate, is a three-disc set) got hearty applause and cheers on both nights. “That Old Black Magic,” the Harold Arlen-Johnny Mercer gem of 1942, was the biggest hit. Why not? It was a hit not only for Frank Sinatra, but for Glenn Miller and Bing Crosby. I wonder if Dylan remembers it best in the hands, or breathy Southern-accented voice, of Marilyn Monroe, parodying it up in Bus Stop (1956).

“Desolation Row,” “Early Roman Kings,” and “Long and Wasted Years” — the first and last with shifting words — were my favorite Dylan songs of the night. Don’t go expecting to hear Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot these days, but I can’t tell you how much I miss that magnificent line “Praise be to Nero’s Neptune.” However, F. Scott Fitzgerald and his books are there in the encore, “Ballad of A Thin Man,” which Dylan is performing these days with sting, bite, and dazzle. And “Duquesne Whistle” embeds itself happily under your skin, and as the earworm of the following day. I whistled it as I drove home that night, and around town the next day.

Saturday night’s concert was even better. It was cooler, and both the audience and the band were looser, relaxed. From his first appearance on stage, playing a “Shenandoah”- sounding song that may be of his own devising (huge points to the first person who can give me a title), Stu Kimball is laying down rhythm that propels many of the songs to greater heights these days. George Recile’s drums, turned down in the mix, enhance and drive instead of drowning out. Most of all, Dylan’s voice is front and center. Enjoy it in all its ragged, raging glory, and concentrate on the phrasing — he certainly is. It’s a pleasure to listen to him emphasize and parenthesize. At the end, Dylan stood for what is for him a long time, looking out intently at the audience. He might have smiled. And then he was gone. People partied long after two of the big tour buses, “the Bobmobiles,” peeled out of the parking lot moments after the show.

On the road again, tryin’ to stay out of the joint

How had Dylan spent the day? Well, folks were good and respectful, and didn’t tweet about it. Dylan had come back to Woodstock, quietly, seeing people and doing things he felt like doing. Since the late 1800s, artists have been coming to Woodstock, and the Byrdcliffe Art Colony snuggles onto the side of Mount Guardian, above the town. From its Arts and Crafts days, Byrdcliffe, founded in 1902, has kept not only painting, sculpture, and visual arts, but music and theater going in the area. The artist residences sponsored by the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild are for artists, writers, and composers; if you qualify, apply and come live on the mountainside for a summer, or longer. Dylan’s Byrdcliffe house, his family home, was on the same road as the Art Colony’s little string of studios, cottages, theater, and the Villetta Inn. On the Saturday when he was in town, Dylan stopped by the artists’ Open House at the Villetta, and in the studios adjacent. The Guild announced his visit after the fact, and sans photograph, except of the venue itself, the Villetta, as it should be. It was a gorgeous day, all day long. The hills and hollows were loaded with bright green new leaves, and lilacs in full fragrant bloom. The creeks were brimming and chattery, with all the waterfalls along Glasco Turnpike and Lower Byrdcliffe, and Upper Byrdcliffe, roads splashing their way down to join the Tannery Brook or the Millstream.

In a town where the post-Woodstock (concert, that is) seekers and searchers and strident supplicants once invaded his privacy and home life, Dylan is well-remembered and spoken fair today. When someone says “Bob,” you needn’t ask who. Every May, for years, a birthday concert has been held for him, featuring both people who played with him on the porch of his Byrdcliffe home, and on stages around the world, and people who became musicians because of him. To hear Dylan and his band on Midsummer’s Eve weekend at the Brickyards, watching the river flow, was magical for many reasons — and perhaps being there was special for him, too.

Part of the Dylan Flotilla