In June of 2014, ISIS magazine published an article by Tara Zuk. The article uses the information from her compilations on this website, and condenses it into a brief overview of Bob Dylan’s fascination with cars and motorcycles.

Read the complete article in document form, or read below.

Reference:

Zuk, Tara. “Do Cars Pass You Up on the Highway?” ISIS 174, June 2014: 42-47

“Hibbing’s got souped-up cars runnin’ full blast on a Friday night”

Bob Dylan, ‘My Life in a Stolen Moment’ (1963)

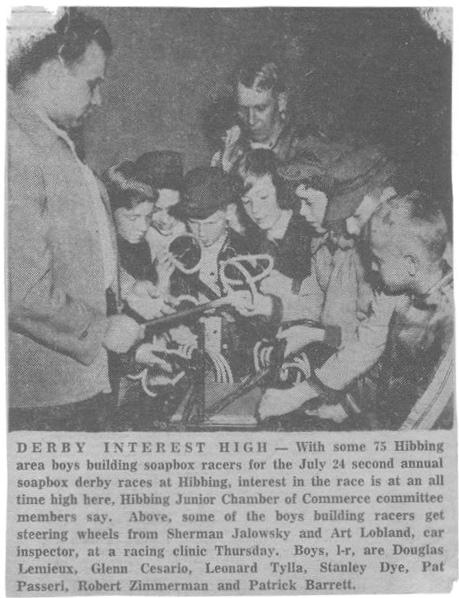

The newspaper article above [circa 1951?] shows a racing clinic for Hibbing Junior Chamber of Commerce. Prospective Soap Box Derby racer, Robert Zimmerman (second from the right) wearing a billed-cap, lays hands on a steering wheel for his Derby car.

The questions remain. What year was this? Did the racer get built? Did Bobby Zimmerman race on July 24 [1951?] at the second annual Hibbing Soapbox Derby race?

And the interest only began with the Soap Box Derby.

Bob Zimmerman was born into a car owning family. Robert Shelton interviewed Bob Dylan’s parents in May 1968, and his mother Beatty Zimmerman reminisced.

Beatty: My father was Ben D. Stone. I had the pick of the crop. He was the lucky one. You must remember I always had a car. It was my father’s but it was like mine. It was a four-door Essex. My Dad said, “You learn to drive, I’ll teach you.” I said, “You don’t have to.” I got in the car and drove away. I just had watched him a few times. Bobby is very much like I am. You either do or you don’t. (Interview with Robert Shelton, May 1968)

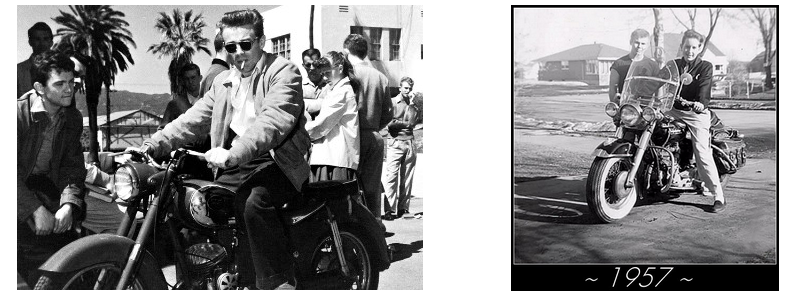

In his biography, No direction home: the life and music of Bob Dylan, Shelton (1986) points out that by the time Bob Zimmerman hit his teens in the 1950s, the traditional American ‘folk heroes’ who inspired the youth no longer rode horses.

They rode motorcycles, drove fast cars, and wore leather jackets.

Epitomised by James Dean and Marlon Brando, these were the ‘wild ones’ whose attitude and individuality spoke powerfully to the teenage Robert Allen Zimmerman.

‘In the basement den, Bob tried to explain that he had stayed to see part of the movie over again. He talked about James Dean and waved his hand towards the walls covered with pasted-up photographs of the dead actor.

‘“James Dean, James Dean, James Dean,” his father repeated. He pulled a magazine photograph of the actor off the wall. “Don’t do that,” Bob yelled. The father tore the picture in half and threw the pieces to the floor. “Don’t raise your voice around here,” he said with finality, stamping upstairs. Bob picked up the pieces of the photograph, hoping he might be able to paste them together. No, he wouldn’t raise his voice around there.’ (Shelton, 1986, pp.23-24)

The best motorcycle rider in Bobby Zimmerman’s hometown of Hibbing was Dale Boutang, a friend of Bob’s who rode a Harley Davidson 74. Bob in turn bought a Harley 45. Bob’s need for speed and rebellious adventurousness led to a reported close shave when racing a train across the tracks from the Brooklyn neighbourhood of Hibbing. Not the last motorcycle incident Bob would be involved in.

Apparently, Bob had several accidents in his father’s car as well as on his motorbike (car-related incidents were allegedly reported to Abe Zimmerman with the euphemistic phrase, ‘I broke the fan belt’). One accident allegedly involved an out of court settlement by Abe of an almost unbelievably high $4000. However, the worst was when Bob was riding his motorcycle fairly slowly, but hit a small three-year-old boy who ran out into the road and collided with the side of Bob’s Harley. The boy needed hospital treatment in Duluth, and Bob was badly shaken by the event. (Shelton, 1986, p.53)

Dave Engel (1997) tells us that early on, Bob did drive the family Buick, but he wanted his own car – more specifically, a pink and white ’51 Ford convertible. Customized, lowered in back, minus the nose piece, with added dual exhaust pipes, fender skirts, fancy hubcaps.

Bob kept pressuring his father, Abe, “Gotta have that car”, and eventually he convinced Abe to go look at it. He knew he really had to have the car when he found out it could get to Minneapolis and halfway back on a tank of gas. A few weeks later, the car was sitting in the Zimmerman driveway. Bob had it painted blue. It was a neat car to drive around town with the top down. But as mentioned, young Bob seemed prone to fender benders. (Engel, 1997)

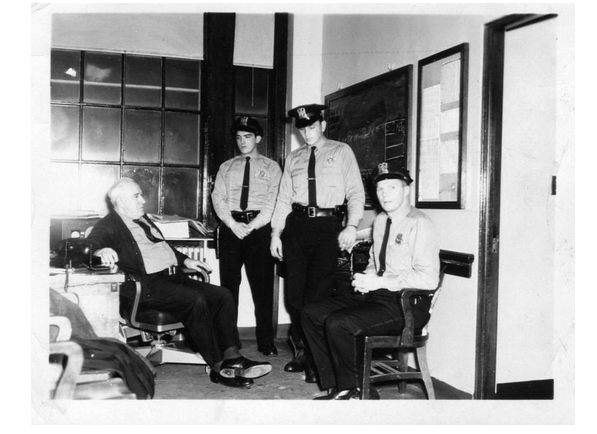

It seems more than likely that his wild driving record, and his history of hanging with a tough crowd, will mean Bobby Zimmerman was known to the Hibbing law enforcement officers during his teen years. Who were they?

Photograph of the Hibbing police, contemporary with young Bob Zimmerman.From left to right: Ed Brigom, Richard (Dick) Frider, Dennis Romano and Archie Passeri. (1958).

In a 1999 interview for ‘On The Tracks’, Bob Dylan’s teenage friend LeRoy Hoikkala, recalled:

“The convertibles… Bob had a ’54 Ford convertible, I had one also. They were used, but nice little cars. They were not expensive cars. We didn’t have new cars. We used (our cars) to promote our dances or rock concerts. We would get these big speakers, horns and two big amplifiers on top of my convertible and we would sit there playing, to advertise our dances. You don’t see that anymore!” (Lindh, 2000)

It was common practice back then for cars to be used in local promotion and raising awareness. Signs on the sides, speakers with music and announcements. The same technique of mobilized public performance for self-advertisement had been employed by The Golden Chords, of which Bobby Zimmerman was a member from 1957 to 1958.

In this photograph, The Rockets join a Howard Street parade [1958?] through Hibbing to promote an appearance sponsored by Bob Zimmerman’s local music store, Crippa Music. Photograph courtesy of LeRoy Hoikkala.

Cars were a symbol of freedom to the post-war youth of America, representing independence, financial stability, movement and an escape route from the small town mentality. But motorcycles represented rebellion, danger and an appealingly edgy cool hipness.

‘In a decade of soft American affluence with no visible frontier to challenge, nothing was better than a bike – unless it was a guitar – to symbolize the young man’s dream of sexual potency, to defy his father and his “safe” car. Harley and Davidson were the Lewis and Clark of the 1950s.’ (Shelton, p.44)

As Linda Fiddler, a high school acquaintance of Bob Dylan’s remembered:

‘Bob was considered one of the tough motorcycle crowd. Always with the black leather jacket, the cigarette in the corner of his mouth, rather hoody. And Echo with her bleached hair and vacant look; That’s mostly how I first noticed him, running around with this freaky girl hanging on the back of his motorcycle, with her frizzy white hair flying and her false eyelashes. It was shocking to me. I tried not to be narrow minded, but I thought that crowd was a bunch of creeps. We used to laugh at the sight of them on the motorcycles. They used to zip through town and it was funny to see them. The thing is motorcycles were taboo because motorcycle guys were automatically bad. I had to stay away from them. They were terrifying, Bob with his big boots and his tight pants.’ (Scaduto, 1971. p. 20)

Marlon Brando in ‘The Wild One’ (1953) with his own Triumph Thunderbird 650cc. Was this the ‘big boots and tight pants’ look that kids like Bob Zimmerman were going for?

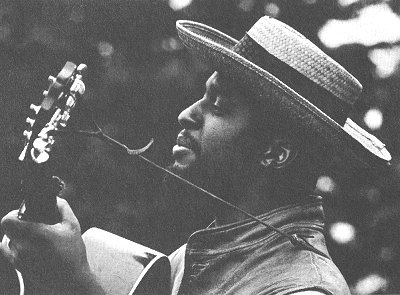

A few years later, just after his arrival in New York City, Bob Dylan recalled a moment with singer/songwriter Len Chandler – who became a real influence on Dylan’s early work – when Chandler’s daredevil exploits were somewhat edgy, even for our intrepid thrill-seeker.

One freezing winter’s night I sat behind him on his Vespa motor scooter riding full throttle across the Brooklyn Bridge my heart just about shot up in my mouth. The bike was speeding on the crisscrossed grid in the high winds, and I felt like I could have gone overboard at any time — weaving in and out of the night’s traffic, it scared the lights out of me — sliding all over the iced steel. I was on edge the whole way, but I could feel that Chandler was in control, his eyes unblinking and centered steadfast. No doubt about it, heaven was on his side. I’ve only felt like that about a few people. (Dylan, 2004, pp.91-92)

Len Chandler 1965

(David Gahr & Robert Shelton: The Face Of Folk Music, New York 1968, p. 191)

“Hibbing’s a good ol’ town

I ran away from it when I was 10, 12, 13, 15, 15 1/2, 17 an’ 18

I been caught an’ brought back all but once”

Bob Dylan, ‘My Life in a Stolen Moment’ (1963)

The young Bob Dylan might never have physically run away from Hibbing (except in his imagination), but the idea of freedom and escape from the small town were probably never far from his mind. The folk, country and blues music he loved often concerned travelling. Moving on. Physical and emotional journeys of wandering. Lonesome highways. Elusive searches for creative and physical freedom.

Bob Dylan explains in his Chronicles: Volume One (2004), that when he discovered Woody Guthrie, it was life-changing for him.

‘My life had never been the same since I’d first heard Woody on a record player in Minneapolis a few years earlier. When I first heard him it was like a million megaton bomb had dropped.

‘I suppose what I was looking for was what I read about in On the Road – looking for the great city, looking for the speed, the sound of it, looking for what Allen Ginsberg had called the “hydrogen jukebox world.”'(Dylan, 2004)

The influence of Woody Guthrie, the Beats, Jack Kerouac, the music… it all led back to that fundamental need to find something bigger and experience that freedom. Hitting the road, hitchhiking, catching trains, riding with friends, owning cars and motorbikes. The symbolism, the movement, the idea of a life and mind in motion and never static.

These are important to the subsequent music, art, ideas, and personae of Bob Dylan.

One of the defining moments of the Dylan myth is the motorcycle crash, which led to him taking time out of the public eye for a couple of years.

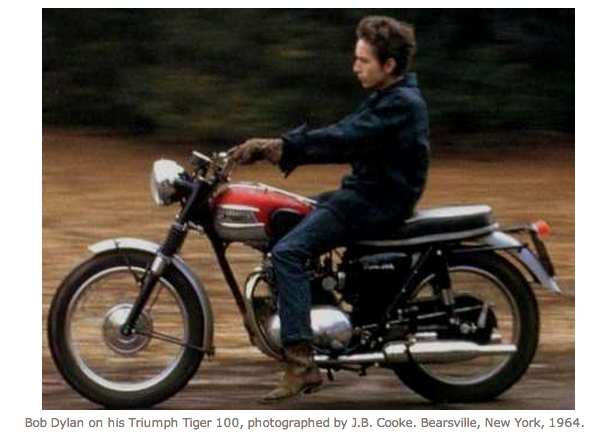

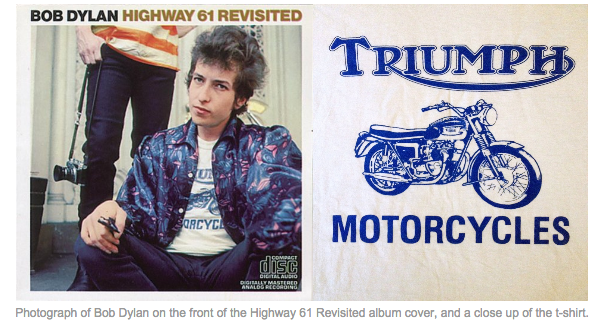

In the mid 1960s, Bob Dylan owned a 500cc, red and silver 1964 Triumph Tiger 100 motorbike. On the cover of his 1965 album Highway 61 Revisited, Bob Dylan is photographed wearing a Triumph motorcycle t-shirt. We remember that his teenage heroes James Dean and Marlon Brando owned Triumph motorcycles.

At a press conference on the afternoon of December 3 1965, at the KQED Studios on Bryant Street San Francisco, the first question was about this t-shirt and photograph. The intensely-posed question was asked by someone later identified as ‘Eric Weil’, who was rumoured to have subsequently spent time in prison and a mental hospital. (Butterfield, 2007-2011)

Eric Weil: I’d like to know about the cover of your forthcoming, erm, album… the one with ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’ in it. I’d like to know about the meaning of the photograph of you wearing a Triumph t-shirt.

Bob Dylan: What do you want to know about it?

Eric Weil: Well, I’d like to know if that’s an equivalent photograph, it means something, it’s got a philosophy in it (Dylan and the audience laugh)… I’d like to know visually what it represents to you. Because you’re a part of that.

Bob Dylan: Um. I haven’t really looked at it that much.

Eric Weil: I’ve thought about it a great deal.

Bob Dylan: It was just taken one day when I was sitting on the steps, you know. I don’t really remember it or think too much about it.

Eric Weil: But what about the motorcycle as an image in your songwriting? You seem to like that.

Bob Dylan: Oh, we all like motorcycles… to some degree. (Gleason, R.J., 1967)

July 29 1966 was the date of the now mythical motorcycle crash, when Bob Dylan is reported to have come off his famed Tiger 100 after the brakes had locked on a road in Woodstock near his manager Albert Grossman’s house. Alleged fractured vertebrae and a lengthy withdrawal from the public eye followed. “Truth is,” Dylan wrote in Chronicles (2004, p.114) “that I wanted to get out of the rat race.”

Was Dylan even riding his Triumph when he crashed on the highway? John Hammond Jr. once added a further twist to the tale.

John Bauldie interviewed John Hammond Jr. on October 26 2006. The interview was published in issue 44 of The Telegraph fanzine, Winter 1992.

The topic of conversation turned to Dylan’s motorcycle crash. Hammond said:

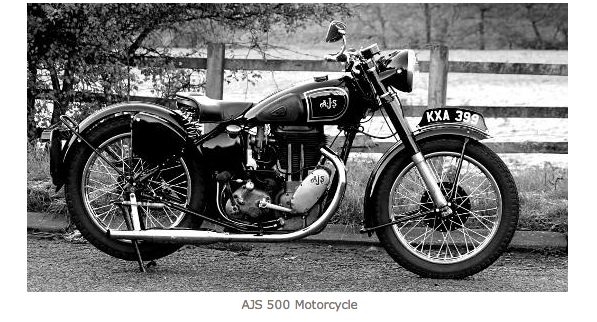

‘Ah, the crash. Well, Jack Elliott had left a bike in Bob’s garage up there. It was an old AJS, a great old bike, 500 single, the kind you can break your leg trying to kickstart. The tyres were flat and I think Bob wanted to have the thing repaired, so… but maybe I shouldn’t say this. This is for Bob to talk about it if he wants to talk about it. It’s not my place to talk about it. Bob did get hurt. I imagine it shook him up to the point where he looked at his life very carefully.’ (Bauldie, 1992)

Jack Elliott confirmed his ownership of an AJS 500, which he says he took back to America from England in 1963, in an interview with the Montreal Gazette. (Montreal Gazette, 2006)

The motorcycle black madonna

Two-wheeled gypsy queen

Bob Dylan, Gates of Eden (1965)

Sometimes, a car is just a car. Sometimes, a bike is just a bike.

However, despite Bob Dylan’s dismissive and bemused attitude toward questions during the 1965 San Francisco press conference about the ‘philosophy’ of the Triumph motorcycle t-shirt, there can be detected a purpose and intention in the use of references to cars and motorbikes in his songs.

Taking a brief look at just a few songs, in a cursory sweep rather than a comprehensive analysis, we can begin to notice some recurring themes and symbolism.

We see, for example, that a vehicle is often used as a metaphor for a relationship. In ‘Tangled up in Blue’ (1974), two people are in an enclosed physical or emotional space, moving through the moment inextricably linked. The line, ‘We drove that car as far as we could / Abandoned it out West’ is followed immediately by the protagonists splitting up as soon as the journey is over and the car (relationship) is abandoned.

There is an extension of this metaphor in ‘Brownsville Girl’ (1986) and also in Dylan’s cover of Hank Snow’s ‘Ninety miles An Hour (Down A Dead End Street)’ (1988), which fits so well with Dylan’s own works; the entire song is a metaphor for a doomed and adulterous temptation. It is of note that the couple who are attempting to avoid the unfaithful pursuit of their desires are in a car, the symbolic representation of stability and responsibility, trying and failing to pay heed to the stop lights and warnings. The impulsive and seductive Devil is riding a rebellious motorcycle.

‘Let’s Keep It Between Us’ (1982) includes the line ‘backseat drivers don’t know the feel of the wheel’. If the car is a symbol of a relationship, or even representing movement along the road of life, the backseat drivers are the people who are vocally interfering in a person’s chosen route without being aware of the position, difficulties or goals of the ‘driver’.

Dylan refers to cars as representing energy, drive, restlessness and the potential for self-destruction (the ‘crash’) as well as progress. ‘This Wheel’s On Fire’ (1967) is an example of such, in a youthful and passionate way, with a touch of irony, sarcasm and gall every bit as much as it is a Biblical/Chaucer/Shakespeare/King Lear “bound upon a wheel of fire” reference .

Embodying the reflection of someone older, we hear in ‘Summer Days’ (2001), ‘Well, I got eight carburetors and boys, I’m using ’em all / I’m short on gas, my motor’s starting to stall’, which could allude to prolonging that drive and motion, pushing oneself to the limits, but recognizing the inevitable constraints of age.

Urban decay and dissolution is represented by the use of negative car images – ‘boulevards of broken cars’ (‘Beyond Here Lies Nothin’’ (2009)) and ‘Where all the cars are stripped between the gates of night’ (‘Golden Loom’ (1975)). They could be said to emphasise the dismal atmosphere of anti-social, emotionally disconnected environments against which the singer is building a contrasting positive image of internal emotional connection. The broken down and abandoned cars reflecting the broken and abandoned personal relationships in a disaffected modern world.

In some songs, specific car models are mentioned and the make of car is significant.

A Cadillac car is an American luxury vehicle. When it is mentioned in ‘Talkin’ World War III Blues’ (1963), the car is in a showroom ‘uptown’ and is only accessible to the protagonist because of the lack of others around to prevent his joy ride. It is a symbol of extravagance and conspicuous consumption – he is alone, believing himself to be the last human being alive in the world, with the freedom to do almost anything… and he chooses to take a Cadillac for a spin!

Returning to ‘Summer Days’ (2001), the song mentions ‘driving in the flats in a Cadillac car’ but the girls describe the song’s protagonist as ‘a worn-out star’. Along with his pockets being ‘loaded’, the car is a symbol of wealth and power against the background of the formerly inhospitable and semi-industrialized environment and the put-down of faded glory by the self-confident youths – which he does not take seriously, but appear to irk him all the same, resulting in a growled, tongue-in-cheek, refutation, “How can you say you love someone else / you know it’s me all the time…”.

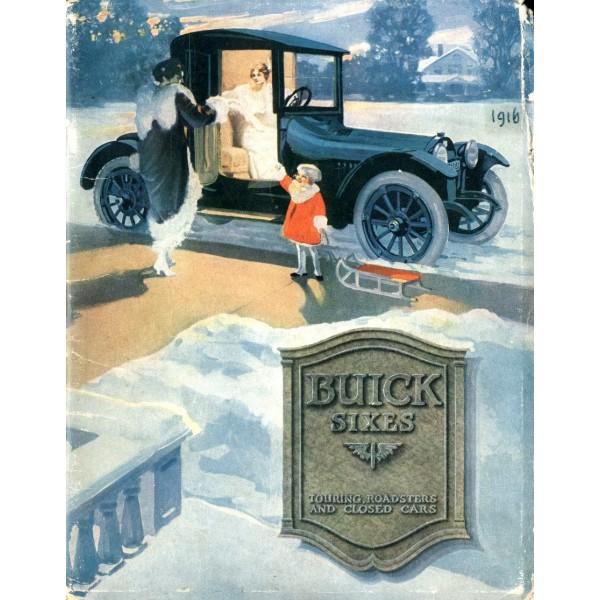

The song ‘From a Buick 6’ (1965) is a bittersweet, metaphor-laden, pounding blues from the album Highway 61 Revisited. The Buick is another American car – not an expensive luxury car like the Cadillac, but still ‘above the norm’ for people earning more than the average. Although only mentioned by name in the title, the juxtaposition comes in writing from a position of relative comfort against the darkness of the other images. It could be the “Buick 6”, the specific model from 1914 to 1930, echoing the blues songs of that time. And it could at the same time bring to mind a later family car, as Dylan mentions in Chronicles how his father had an ‘old Buick Roadmaster’ into which he would load the Zimmerman boys for weekend trips out of Hibbing to visit family in Duluth. (Dylan, 2004)

‘Union Sundown’ (1983) is a song with a clear political point. When the protagonist says ‘the car I drive is a Chevrolet’ it is a best-selling American car, but it is from a company who have outsourced their production over the years (‘it was put together down in Argentina / by a guy makin’ thirty cents a day’). It is a statement about the loss of American jobs, the downsides of capitalism and the mistreatment of foreign workers within a single line. This is more poignant as the car is so indicative of core American culture and pride in the post-war years. Dylan is singing here about similar issues to those raised in the media by his February 2014 Chrysler commercial.

In ‘High Water (for Charley Patton)’ (2001) Bob Dylan sings, ‘I got a cravin’ love for blazing speed / Got a hopped-up Mustang Ford / Jump into the wagon, love, throw your panties on the board’. The Mustang is a sports model of the American automobile giant, the Mustang I was built in 1961, the production model Mustang came onto the market in 1964. The craving for speed and the sexual comment to throw your panties on the [dash]board, often misheard as overboard, can be seen as a reference to trying to regain that feeling of freedom, living on the edge and sexual potency – back when he wasn’t short on gas with his motor starting to stall? Certainly, it hearkens back to the emotions and symbolism of the vehicles from Dylan’s teenage years. A hopped-up car has had the engine given added power, a hopped up person is stimulated with the aid of drugs.

The 350 car Hibbing Drive-in Theater, 313 Mesabi Drive, Hibbing, MN 55746, opened in 1955 and was sold by the family in 1980. It closed in 1985.

Bob Dylan grew up as a teenager in 1950s America. It was the age of drive-in movies, hot rods, motorcycles, and drive-through restaurants with car-hop service. The teen movie idols were nothing without their ‘wheels’. Financially, cars were becoming more affordable for the average family and it became part of the ‘American Dream’ to explore those endless open highways. Rock ‘n’ roll continued the American automobile love affair. Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley eulogised the motor vehicle, while many popular songs focussed on such cars as the Rocket 88, Hot Rod Lincoln, Brand New Cadillac, Coupe de Ville and even the odd Thunderbird.

Young Bobby Zimmerman was not immune. Music, freedom, rock ‘n’ roll, girls, the open road and the allure of power, independence and beauty in heady combination.

Consider those embedded seam lines of car-based imagery and metaphor threading their way through Bob Dylan’s songs, poetry and writing; the various influential road trips he took with friends and colleagues at different points in his life (a complex subject that warrants treatment in an article of its own); the fact that even sections of Bob Dylan’s iron gate sculptures for his ‘Mood Swings’ exhibition (2013) include recycled car parts. Omnipresent automobile influences impact his art. These things run deep.

‘how come you’re so afraid of things that dont make any sense to you? do people pass you up on the street all the time? do cars pass you up on the highway? how come you’re so afraid of things that dont make any sense to you?’ (Dylan, 1971)

Bob Dylan selecting pieces for his sculptures from the ‘Auto’ section of his scrap metal collection. Photograph by John Shearer, 2013.

References:

Bauldie, J., 1992. Interview: John Hammond Jr, The Telegraph (44)

Butterfield, M., 2007-2011, Zodiac killer facts. [online] <http://www.zodiackillerfacts.com/belli.htm> [Accessed 3rd March 2014]

Dylan, Bob, My life in a stolen moment, Columbia Records, 1963

Dylan, Bob. Tarantula. New York, N.Y: Macmillan, 1971.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004.

Engel, Dave. Dylan in Minnesota: just like Bob Zimmerman’s blues. Rudolph, Wis: River City Memoirs-Mesabi, 1997.

Gleason, R.J. 1967, Bob Dylan gives press conference in San Francisco, Rolling Stone Magazine, December 14, 1967. [online]

<http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/bob-dylan-gives-press-conference-in-san-francisco-19671214> [Accessed 3rd March 2014]

Lindh, Lars. An exclusive interview with LeRoy Hoikkala, On the tracks : the unauthorized Bob Dylan magazine, Grand Junction, Colorado, USA : Rolling Tomes Inc. Issue 18, Spring 2000.

Perusse, B., 2006. Q&A with Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Montreal Gazette, October 3, 2006. [online] <http://www.canada.com/story.html?id=76e782ad-1226-43af-9b73-8ba3fee2eb52> [Accessed 3rd March 2014]

Scaduto, Anthony. Bob Dylan: an intimate biography. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1971.

Shelton, Robert. No direction home: the life and music of Bob Dylan. New York: Beech Tree Books, 1986.

Shelton, Robert. Interview with Abraham and Beatty Zimmerman. Hibbing, May 1968

(c) Tara Zuk, 2014

All Rights Reserved