Album Review: Phish–Joy

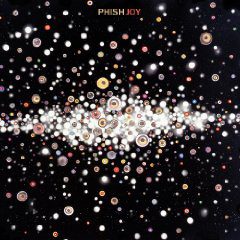

Phish–Joy–Jemp–September 2009

The 14th studio album from Phish, and their first after a five-year hiatus that ended with a series of reunion shows in March, starts with “Backwards Down the Number Line”, a Dead-style piece of sunny roots-rock that finds singer/guitarist Trey Anastasio’s vocals taking on a smoother sheen these days—close to Eric Clapton’s timbre—perhaps thanks to the steady production hand of Steve Lillywhite, back with Phish for the first time since 1996’s Billy Breathes. Across the song’s three-minute mark, Anastasio starts soloing in a familiar meander, which reaches the four-minute and then five-minute mark, and you can imagine a collective smile from the faithful and a collective groan from the doubters.

And that’s the quandary that Phish faces on its studio work—the difficulty of capturing the eclectic exuberance of their unpredictable live shows, which have always been far more about vibe—or dancing or drugs or community or fashion—than about songs. Detractors have long leveled the same criticisms at Phish that plagued their forbearers, the Grateful Dead: that they weren’t songwriters enough to produce good studio records, that their endless instrumental jamming was pointless and boring, that the band lacked skillful singers, and that many of their fans were too altered to notice (or care) when the band played poorly.

While Phish’s instrumentalists are undoubtedly first-rate, sometimes dazzling, some of those criticisms indeed apply. It’s true that the protracted jamming, with Anastasio going up and down the pentatonic scale for 20 minutes, can, after awhile, be mind-numbing. Still, it’s silly to blame Phish for noticing that the longer they noodle around, the more the kids in the audience act like their minds are being blown and that jamming is where the ticket-sale revenue is. Furthermore, the band’s impressive alacrity for playing different styles, taking improvisational left turns, learning songs on the fly, never playing the same set twice, etc., make them worthy of serious musical respect and not just the best band to lead the post-Jerry legions of mushroom-and-hackeysack enthusiasts.

At the same time, it’s true that Anastasio isn’t much of a singer—he has limited range and struggles with intonation and control—and that Phish has released a long string of unremarkable albums. Their new album does little to break that pattern. With Lillywhite at the knobs, Joy sounds fresher and more lacquered than most of Phish’s others—it’s no coincidence that Billy Breathes is widely considered the band’s best record to this point—but there simply isn’t an exceptional song anywhere to be found on the album.

On Joy, Phish makes attempts at reigning in unnecessary waywardness and tightening song structures, but the songs are uniformly flat and unconvincing genre exercises. “Stealing Time from the Faulty Plan” is a bluesy rock sway, with Anastasio punching tight licks into your left ear, but it’s boilerplate stuff, following the band’s usual any-old-melody-will-do policy. Plus, longtime lyricist Tom Marshall continues to be a liability, providing cryptic faux-mystical lines that are impossible to explicate, let alone resonate. When the lyrics are fairly lucid, Anastasio is forced to sing ham-handed phrases like, say, the aforementioned titles: remembering the past is going “backwards down the number line” and changing directions is “stealing time from the faulty plan”. As lines like these start to accumulate, they bog down even the most engaging of the record’s melodies.

Elsewhere, Phish tries a big, soaring ballad with the title cut, which is reasonably pretty but is hampered by Anastasio’s shaky delivery. “Sugar Shack” , a reggae-fusion tune full of syncopated organs and toms, would pass for Steve Miller if it were catchier. And after some straight-up rockers, like the bar-band juke of “Kill Devil Falls”, the ‘60s-style psychedelia of “Light” finally gets spacey, all sparkling guitar and frantic drum counterattacks, which works to decent effect since the band at least settles on a sound that feels like their own.

Joy’s reach for the golden ring, though, is Anastasio’s 13-minute multi-part suite, “Time Turns Elastic”, which starts off with a stabbing piano melody and layered vocal harmonies and slows to a ‘70s prog ballad before morphing into an interlocking series of instrumental crescendos and breakdowns, guitar arpeggios, time-signature shifts, piano gambols, and jazzy modal interludes. It’s like Emerson, Lake, and Phish. As tricky, ambitious, and overall impressive as the piece is, by the end of it, you may be crawling at the window for air, and even Phish fans will find little to shuffle and twirl to.

As one of America’s most consistent concert draws, it’s admirable that, after so many attempts, Phish still has such ardent desire to be taken seriously as recording artists, rather than to simply stop trying as the Dead did. And while it may continue to be unfair to compare Phish’s live shows to their studio work and that Joy is a nobler attempt than most of their other albums, Phish’s strengths and, most noticeably, their limitations are nonetheless as evident as ever.

This review was first published at PopMatters.