Country on a Bended Knee

Bruce Springsteen warned us that the darkness was on the edge of town. John Henry has upgraded the threat level: The darkness has crept into our neighborhoods.

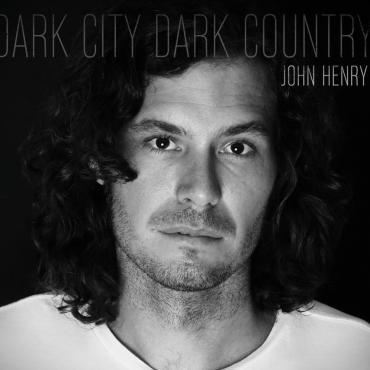

Dark City Dark Country is Henry’s most recent album, and you would be forgiven if you assumed that it was written and recorded since the election of President Donald Trump. It was not. But, as Henry says, “I feel his presidency has exacerbated a lot of these things.”

These songs, produced and recorded, with one exception, in St. Louis by Henry and David Beeman, deal with issues that have lingered, if not worsened, over the years: gun violence, addiction, fear of “the other,” lack of hope and opportunity.

The title song, for example, describes a place where “no matter where you say you’re from/ it’s someone else’s fault,” a place where we “can’t afford to feed a sick little girl/ Dark city, dark country, dark world.”

In addition to love vs. loss and hope vs. desperation, Dark City Dark Country’s canvas spans urban vs. rural.

“I was raised in the city of St. Louis, and my wife was raised in a small town called Old Monroe (on the Mississippi River less than an hour north of St. Louis), so for the last 15 years, I have been spending huge amounts of time in both places,” Henry says. “And the genesis of this record was living in between those two worlds and seeing the commonality and differences.”

The darkness of many of these songs is lightened by first-class heartland rock leavened in a couple of tunes by some bouncy, Mumfordsy background vocals. Dancing might just be allowed at the apocalypse.

Henry, a veteran St. Louis musician, has gone solo on Dark City, dropping “and The Engine” from the marquee. The move has widened his palette, and the album boasts some of St. Louis’ finest musicians, including Bottle Rockets guitarist John Horton.

The album’s first single, “Fade to Black,” is a spare rocker whose protagonist is dealing with demons and a lack of hope. The song is the soundtrack to the record’s first video as well. In the hands of Henry and filmmaker Tim Maupin, “Fade to Black” turns into a quick-cut story about a man unable to cope with his lot, who sheds his wife and identity for a life of anonymity and odd jobs. But like the album itself (more on that later), it ends on a note of hope with a phone call home.

On “Broken City,” which dates back a few years and was produced by Nashville favorite Dave Cobb, Henry sings “Better tame those wild eyes/ So that you start to see,” warning that only fool’s gold is to be found amid a cacophony of screaming talk radio hosts and electronic preachers.

Henry met Cobb – who has come to prominence on projects with artists ranging from Chris Singleton, Jason Isbell and Sturgill Simpson to Mary Chapin Carpenter, Chris Isaak and Beck – when he auditioned in Nashville for a spot in the Wild Feathers. He didn’t get the gig, but the Cobb connection was made.

Recording with Cobb was “an amazing experience,” Henry says. “He is really great to work with, everything is very natural and stress-free. I was really proud of that song and the record we made of it. We ate at the Waffle House a bunch while recording it, and life was good.”

Perhaps the album’s most poignant song is the lead track, “Country of the Broken Hearted,” a post-Newtown treatment of gun violence and its effect on a child. From breathless accounts of a school shooting on radio and TV and empty calls to never forget, Henry sings:

“My little girl she is just a baby/ She still sleeps with the nightlight on/ She comes to wake me with her nightmares/ Daddy, hold me in your arms/ And so I hold her in my arms/ … The country of the broken hearted/ The country on a bended knee.”

“The Professional” deals with the opioid epidemic in America (“White lies, white pills/Dark skies, dark hills, the professional”); and “Lightning City Blues” features these chilling, ripped-from-current-news lines: “One strike of the pen sends the army to make news,/ strike up the band, got the lightning city blues.”

All is not bleak, however. The album’s final song, the anthem “Wave to the Sky,” exalts the hope that exists in love and family, a way to perhaps keep the darkness at bay:

“In the house where we raise our kids,/ we keep the fire from the door./ In the city and the countryside, / the sun comes up once more. / We made it through the darkest hour yet, /chased down the ghosts that followed everywhere we went.”