Guy Clark & His Craft: The Turnstyled, Junkpiled Interview

Guy Clark and His Craft: The TJ Interview

By Courtney Sudbrink, Editor

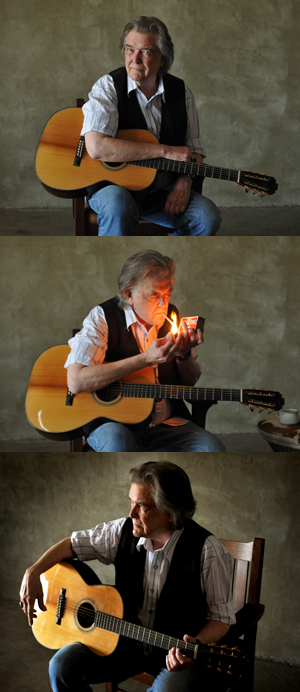

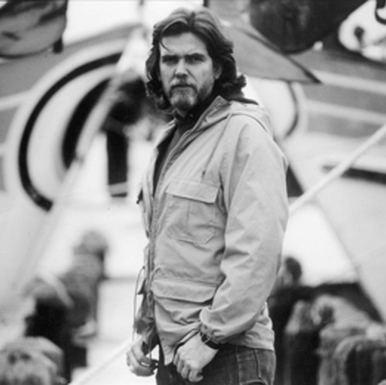

Guy Clark is a writer’s writer. He puts the work in. But somehow it always seems effortless. And that’s what’s so great about him.

With that trademark Texas twang and slow, soulful drawl, Clark’s as cool in demeanor and tone as the stories he tells and words he sings suggest. Part confidence, part comfort, he’s a man at ease with himself.

It translates into everything he does.

Guy Clark “Sis Draper” (Sugar Hill Records)

But alongside his laid-back attitude lies tremendous discipline, dedication to craft and sincere appreciation for having been able to make a living from his life’s passion. With a masterful penchant for prose that stands

A longtime Nashville based songwriter of the highest regard he has been a unique force in the world of roots music for five decades and shows no signs of slowing down. His vast canon of hits includes standards such as “Desperadoes Waiting For a Train,” “Texas 1947,” “She Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” and most recently “Hemingway’s Whiskey,” to name only a few. In his senior years, Clark is distinguished, virile, wise and leads by example. In other words, he stands for all that a writer ought be.

In contrast to that which represents Clark and his legacy is Los Angeles: a city often absorbed by the chaos of the industry it relies on. A tough town for anyone with true passion for delivering honest odes to humanity and undisturbed landscape, it’s no surprise Clark got out when he did.

Not only was it “too cliquish,” for his taste, but Clark also pointed out the harsh reality of quality of life here back in the late 1960s. Between environmental concerns and clogged commuter highways, LA wasn’t and isn’t a place suitable for the easygoing Lone Star State native.

“I lived [in LA] for about a year before I moved to Nashville and that’s back when the air quality was just horrible. I mean, the sky was yellow; it burned your eyes to go outside,” Clark recalled.

Of course, this fish-out-of-water situation that came at the beginning of the now celebrated troubadour’s professional career was at a time when he was struggling to figure out where opportunity in the business would take him. But for someone so in tune with the importance of preserving what comes natural, it didn’t take long to figure out he needed to make a change. Though he was only in LA for a short stint,

In true from, a year later, it led to his penning one of the most accurate depictions of life in Los Angeles to date, an anthem for those who can commiserate. But like is such with all of his work, Clark simply told his truth.

With a frankness that parallels that of the Sin City’s cynical truth teller, Charles Bukowski, “LA Freeway,” is a reflective farewell that is heavy on the courage and grace the novelist never achieved. Unlike Bukowski, Clark isn’t bitter. He doesn’t drag listeners down. Rather, he embraces differences and finds the positive where it isn’t always obvious.

“I know some nice people and [LA] is beautiful actually. It’s just… that’s a hard place for me to live,” he explained.

Upon earning a publishing deal in 1969, with Sunbury Music that offered him a steady paycheck, Clark made the move to Nashville, where he found the good in people and environment much easier to come by. The slower Southern pace was far more conducive to his preferred lifestyle.

“It seems to offer the least resistance for me personally. It’s just so much easier for me to live here. I like it easy, I don’t like things being a hassle,” he continued.

When Clark first arrived in Nashville, it was a place where he could flourish alongside his peers. In combination with the hospitable, down to earth culture, his new home led him to the resolution he was looking for.

“There’s so many good, talented, brilliant writers and guitar players and most everybody is real friendly. Here it’s like, man if you want to stroll in and see Chet Atkins, you can do it. There aren’t two armed guards and three armed secretaries,” he added.

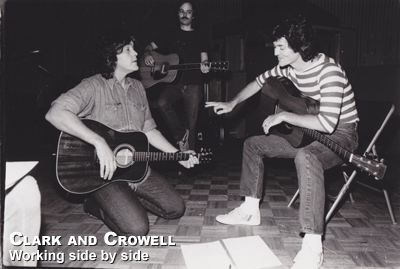

Since his early days in Music City, Clark has always had an open door policy that falls inline with his appreciation for being able to see performers in quaint, intimate settings. Captured in the definitive documentary of the era, Heartworn Highways (1975), Clark is shown in his element,

“That sort of thing was fairly regular. We lived pretty far out of town so it couldn’t happen every night. People weren’t just dropping by. You wanted to come you had to have a reason,” he explained, humorously continuing with irony that, “anyone who called could come.”

Though Nashville was a small town compared to Los Angeles when Clark first arrived there, it is still dominated by The Business. So, when writing songs is one’s job, Nashville, Clark says, “is where you get it done.”

And despite commercial demands that don’t always fall in line with his level of authenticity, Clark has thrived by remaining on the outside of the madness that surrounds the cutthroat aspects of the industry. For him, it has always been about camaraderie.

“That

A key catalyst in what is considered a revolutionary movement representing all music should be in its purist, most unadulterated form, Clark has always been a purveyor of building genuine relationships and fostering individual skill.

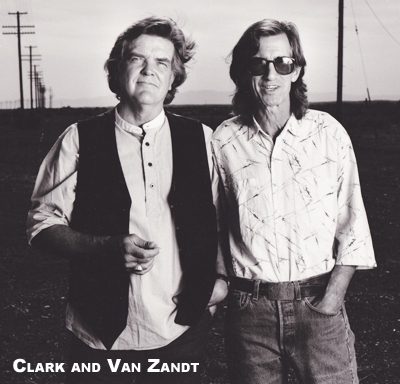

Dating back to the foundational days in the mid 60’s as an active participant on the Houston Folk circuit alongside fellow Texas Troubadour, Townes Van Zandt, he has continued to hold the importance of brotherhood and bond between men in the highest regard. Now, even fifteen years after best friend Van Zandt’s passing, it is clear the late songwriter’s memory is never far from Clark’s thoughts.

“I’m lookin’ at a picture of [Townes] right now,” Clark revealed with warm sentimentality. “I have a really great picture of him hanging on my wall and it just happens to be where I’m sittin’,” he continued.

Knowing that Van Zant and his songs still play a significant role in today’s music comforts Clark. He maintains that the late songwriter’s body of work is crucial to the world. Their relationship was one of reciprocal reverence.

Still, even though the two men drew inspiration from one another, both were solitary when it came to writing. They often worked side by side, but it was never in a competitive way. They were simply there for each other, coming from places of encouragement, testing out new songs and listening in awe of one another’s unique abilities.

“We never tried to write together it was all just a mutual admiration through that,” Clark explained.

In many ways, Clark and Van Zandt were similar. Both, strong individuals with authentic voices who wrote incredible songs; but where Van Zandt famously struggled with inner demons, Clark didn’t. Thus, it made the friendship difficult at times for the whimsical and energetic Clark.

“Townes was really crazy and I’m not. Townes was what he was. He was a brilliant, brilliant person, writer… he was the funniest son-of-a-bitch I ever met in my life. His humor. His quickness of mind,” he fondly recalled.

Clark is no stranger to humor and intellect, himself. That sharpness and wryness common in Texans, is one of his defining qualities. Though he has the ability to write songs that cut to the core, he also appreciates the lighter side of the art.

When it comes to clever songs, Clark excels. Such as when he writes about one of his true loves, that is, food. A recurring topic in his work, it comes from a place of joy and probity, qualities that do well in reflecting his happy-go-lucky personality.

“I don’t consciously think about writing songs about food,” he explained with an air of coyness. Being called out on his adoration for the tasty things in life is a little embarrassing for Clark who has long been teased by friends on the matter.

Of course, this only lends to his likability. And his glorification of basic human needs ha

“’Homegrown Tomatoes’ came out because I was sitting there watching my tomato plants grow and I thought, ‘These guys need a song.’ Music is suppose to make plants grow,” he said.

To some, tomatoes wouldn’t be an obvious subject for a brilliant song, but Clark suggests it is the simple things that are remarkable. He has a knack for finding the poetry in everyday life.

“When “Texas Cookin’ happened it was ‘cause I was sitting there thinking I wish I was in Texas so I could get some good Mexican food,” he added.

“Texas Cookin’” stands out as one of the funkiest songs ever written. It has that signature groove only Clark can produce. Capturing the exuberant energy of the time and the feelings of carefree days spent with good friends around a backyard BBQ, Clark is able to borrow elements from other cultures without ever lacking genuine understanding of what it means to play in a certain way. His style, rooted in that of diverse communities, all of which he acknowledges for their richness.

“The first music I got turned onto was Mexican music in South Texas. Then I moved to Houston and I was around guys like Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb, you know old blues players. And I just loved what they did. They were writing their own songs,” Clark explained.

While “Texas Cookin’” along with songs like “Rita Ballou,” “Ballad of Laverne and Captain Flint,” and “Don’t Let The Sunshine Fool Ya,” all have that killer beat, it isn’t something Clark sets out to create. He is so in tune with what the culture and experience represents, it gushes from his work. His range of influence is something he embraces, but he makes whatever he plays distinctly his own.

“I’m not a blues singer,” he said, “ I’m not a white boy singing the blues, but what you take from them is that groove. It’s fascinating. That’s what you take from them. Not how you play.”

Clark’s rules aren’t necessarily in sync with the curr

“The music’s not the same. What they call Country music. I’m not really a Country music singer or songwriter,” he stated.

The great paradox of course, lies in the fact that Clark is known for writing songs for some of Nashville’s most prominent and successful commercially minded Country artists. His latest contribution, “Hemingway’s Whiskey,” was the title track on Kenny Chesney’s 2010 hit album. The song, which uses the Lost Generation’s patriarchal novelist as an anecdote for conveying the common traits, dispositions and struggles of a writer, something Clark knows by heart.

But whether or not an artist performs a song the way it ought to be doesn’t affect Clark. Allowing others to sing his songs is what pays the bills. He has always taken solace in the fact that if anyone wants to hear a song the right way, they can listen to his version. That is, the definitive one.

”I read his short stories and I liked them because they were short. He was very sparing with the English language,” he explained.

Those attributes ring true for Clark and his meticulous approach. His songs themselves are short stories. With strong, distinct characters, they are vignettes of American life, so engaging because of the candor and form Clark implements. Not only are both men characterized by their poignancy without pretension, but they also followed the innate sense of having to do what they were born to. By his own admission, Clark recognizes that he shares traits with Hemingway, but humorously adds, that he has to “make it rhyme.”

Clark’s understanding of the importance of process, along with his homespun humility, are two reasons why he continues to be a key mentor to aspiring songwriters. His philosophy: “Write with a pencil and a big eraser,” is vital to understanding the work involved in creating masterful pieces that add value to the lives of anyone who hears them.

But although he is able to advise young artists on the right way to develop one’s craft, he has a show-don’t-tell approach and egalitarian nature. The perfect combination for passing along the torch to up-and-coming roots purists, his rudimentary, yet fundamental advice is something that ought be heeded by writers of any specific variation.

“Write what you know about and try to not master, but to be facile with the English language. To know what you’re talking about and to know what words mean. To know when to ignore that and when to sit up straight and do it right. I would think writing in any form demands that,” he offers.

Clark is a guru when it comes to songwriting, but he’s never lost touch with the leisure his profession provides. He still has the same youthful vigor that has been essential to his cool-as-can-be presence as a performer. Because of his fortune of being one of America’s most prolific storytellers, he is able to enjoy his time and focus on his right-brained passion for guitar making.

That, along with simple pleasures like relaxing and having a conversation, is, as he admitted, “what being writer means” to him. His sanctuary like environment and position in life is something he is nothing short of grateful for having obtained.

“I’m in my workshop where I build guitars. How much better can it get?” he said.

Clark’s workshop functions as a hideaway from the industry and is considered by music enthusiasts to be like visiting the Lincoln Monument of songwriters. Though Clark recognizes that, over the years, Nashville is becoming more and more representative of the negative qualities Los Angeles is faulted for and as time passes, it becoming increasingly difficult to tolerate. Even for someone who for the most part, has been able to work in isolation to avoid the less than desirable aspects of the increasingly brand-driven city, it is may be headed towards a breaking point for Clark.

“It’s changed over the years, but not so I can’t live here. I mean it’s getting close. I always say if I ever break even, I’m moving back to Texas,” he joked.

Still, Nashville is the place where he has been able to work. Though as he confessed, “No place really suits me except Texas,” Clark accepts the fact that his career momentum can be credited to his close proximity to the place where stars are made. However, he isn’t one to rest on his laurels. He holds dear, that his best work isn’t behind. Rather, it is in front of him.

“There’s a lot of good things that have happened to me. They just all seem to be in a continuum. I probably felt like the highlights of my life were every time something happened to me. I don’t think of one that sticks out. I’m waiting to see what happens tomorrow,” he said.

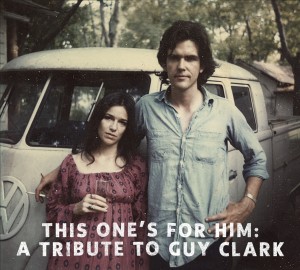

Because of Clark’s endurance and continued devotion to his craft, it’s quite possible that may be the case. His career, monumental in terms of reach, quality and perseverance make it no surprise legends like Kris Kristofferson, Lyle Lovett, Steve Earle, John Prine and some-time writing partner, Rodney Crowell, among many others, all banded together to pay tribute to Clark on the recent album This One’s For Him: A Tribute To Guy Clark, which re-examines Clark’s work with the due freshness and care required.

“That was amazing! I think it’s really good. You know, I get a little embarrassed I guess by that kind of stuff,” Clark stated.

Though he may not be comfortable as the center of attention, the album was a perfect way to celebrate for his 70th birthday and is a fine addition to his ever-growing legacy. As Clark once said of Townes Van Zandt, “we’re all better” for being exposed to his songs. With a slew of talented contemporary artists, such as Van Zandt’s son, John Townes Van Zandt II (who sounds hauntingly like his father on “Let Him Roll”) to Hayes Carll, alongside some of Clark’s most impressive contemporaries, it is clear that his music will be required listening for generations to come.

Guy Clark’s place in American culture is timeless. He eloquently describes the true power and beauty of human achievement. As he continues to share his gift, writing and playing “for the folks,” it is plain to see why he is one of this country’s most respected songwriters. His coolness and his craft, the things that best define him. When it comes to honest songwriting, Guy Clark is and will always be the benchmark standard.

Guy Clark Week at Turnstyled, Junkpiled