Gary Atkinson of Document Records – Keeping the Blues Alive!

DATC: Gary, tell us what Document Records is and what makes it special?

Gary: It is rather unique! I was a CD reviewer when I first encountered it. From the 1970s onwards there were labels that were reissuing pre-war country blues. Artists’ works were being released in chronological order – labels like Matchbox, RST, Wolf and so on. Johnny Parth was involved in some way with these labels. He was producing albums for a few different labels, both here and in Austria. Johnny did a tremendous amount of work on different projects and he was able to get access to a large bank of original recordings. Eventually he realized he had so many recordings he could mass them together and put it under one umbrella, one label. And so Document Records was born.

And he started releasing these recordings at a prolific rate – he actually was releasing about 100 CDs a year! He’d struck up a very good deal with Arhoolie in San Francisco whereby they agreed to take and pay for 250 of any CD that Document released. That’s any record label’s dream! It’s usually sale or return. So that financed Document in the early days.

And the first 200-300 releases of the catalogue were very strong sellers and are still popular today. But eventually Arhoolie had to implore Johnny to stop sending CDs, as they began to cover much more obscure areas that were not so popular with the record buying public – these included old preachers and sermons! Johnny didn’t take any notice of this request. So it got to the point where the Arhoolie warehouse was stacked full of Document CDS!

DATC: You got involved about 12 years or so ago?

Gary: Yes. What Johnny had done in releasing the works of artists like Blind Willie McTell chronologically was unbelievable, really. It took a certain type of person. After doing the reviews, Johnny desperately needed someone to write some booklet notes on four volumes of Ma Rainey and he asked me. And no matter what you did for Johnny, he would pay you in CDs! 10 CDs for a set of booklet notes, so I was amassing quite a bit of the catalogue – my idea of heaven really – I don’t know whether he went down to his local supermarket and offered to pay for his groceries in CDs or not!

This was around 1997 and it was at the beginning of people having PCs in their homes. And it occurred to me – a website would be great to reach out to all the fans of pre-war blues around the world. Perhaps you could make a kind of online shop – so I called Johnny and put this to him, but he just wasn’t interested. But he said – why don’t you have a go at it? And then he said, would you like all of Document? And I assumed he just meant that I could have the rest of the catalogue I didn’t have. But it soon became clear that what he meant was that he wanted me to take over Document Records.

So we talked about a deal and I said yes.

DATC: And you took over the business at that point and have seen it through the whole sea change of CDs through to downloads.

Gary: Actually I couldn’t have taken it over at a worse time – the timing was appalling! But I had committed myself to it. And it’s not like selling a commodity – there’s a much bigger weight of responsibility on our shoulders because we are acutely aware that what we have is as good as a kind of museum, with lots of precious stuff inside it. If the door was closed on it and the key thrown away, it would be a huge loss. Independent record companies have always been a bit of a thorn in the majors side. If companies likeDocument finished, the majors are not going to their vaults and say, we simply must do a boxed set of the Rev. J M Gates, orFrank Stokes. These companies are not interested in licensing anything unless it’s likely to sell up to 20,000 copies. The money side of it doesn’t particularly bother me, but what might keep me awake at night, is thinking – if Documentwasn’t around, who would take up the challenge of this precious repository of material?

Often we get orders from universities in the States and we have this curious and ironic situation where the University of Texas is ordering pre-war recordings of Texas blues artists from a little sleepy hollow in the south west of Scotland. And they need this not only for music studies but African-American social studies and so on. But what if Document weren’t around?

DATC: So if you had to articulate what is it about this early blues music that is so important, so vital?

Gary: I think that Jack White summed this up quite well a few weeks back, when he said that this was really the first recordings of ordinary people singing about their own very personal thoughts and feelings. Before that you had vaudeville, music hall songs, minstrel singers and so on – they were not personal songs. It was this or classical music. So this idea of people singing about the fact that they have money troubles of love troubles…blues music was so individual, so personal.

DATC: How have you found interest in the blues over the past, say ten years? What’s been your observation?

Gary: I think it’s still pretty much where it was in the late seventies. Up until 1961, it was black music for black consumption. Live performances, whether in a Chicago club or a juke joint down south – it was black performers for a black audience. More often than not these audiences wouldn’t just sit in their seats and clap politely – one of the first blues records I remember hearing was White, Brown Black by Big Bill Broonzy and I made the wrong conclusion that a lot of this stuff was going to be political. But it’s not, they are songs about love. Some of it is incredibly romantic, some of it absolutely brutal. But nearly all of it was danced to. You’d go into the juke joint and you’d have some couple doing some sort of grinding dance in the shadows to something like Charlie Patton’s Hammer Blues.

For us something to dance to needs to be energetic – it’s hard for us to get our minds around the fact that a lot of the pre-war music would have been danced to.

DATC: Elijah Wald makes the same point in his book Escaping the Delta, that whatever else you want to say about the blues, it was music to dance to. It was entertainment. It was a way to escape the hard week of cotton picking and then into the juke joint to be entertained.

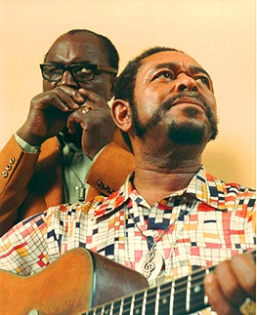

Gary: Going into town on a Saturday night to the barrelhouse or the juke joint, drinks, hot evenings, people dancing, people talking in the shadows. Now the black record buying public follow the trends just the same as anybody else did. For them it was blues, then swing, then R&D, the boogie-woogie stuff, the swing stuff, then the powerful Chicago electric stuff – they were moving with the times. It was over for pre-war blues recordings and they moved on. And they moved on from the electric blues to soul. And then it became all the more sophisticated. So the likes of Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters – fantastic as they are, and despite how you and I might appreciate them, by the end of the 50s it was becoming old music. And by the time Tamla had got a hold by the sixties, they were done, more or less, they only appealed to the older generation which had grown up with that music.

But then of course we have the Rolling Stones and the Animals, the Yardbirds, Cream. And they, unwittingly, brought another audience to this music. The record companies – like Chess – had been approached regarding artists going over the Europe to tour. All you’d had before that was Bill Broonzey, Lonnie Donnegan, and

DATC: Do you have any contemporary blues artists you particularly like?

Gary: No, not really! When you’ve been listening to this stuff all your life, probably for several hours every day… When I started off with this, to go into a record shop with a blues section would be very unusual. And one of the things about the music back in the day was that it was very obscure, and when I was at school, the other kids would have things like T-Rex and Sweet written all over their school satchels, whereas I had things like Barbeque Bob and Peg Leg Howell! Those times were very lonely experiences! So I’ve been into this for such a long time, and when you hear something new, you’re saying to yourself, is this is just like so and so, and as the years go on you end up with these massive references you can make. So it really takes something to make me sit up and listen. But it’s nice when you hear someone these days go down, not the Buddy Guy route, but more the down home route. That’s what I like.

DATC: Is there a typical Document Records customer?

Gary: [laughs]. Yes, they’re very scary and frightening! No, actually there isn’t – when I’d had Documentabout 4 or 5 years, somebody said, do you remember the Blues and Gospel Train? It was a programme on Granada TV around 1963 or so, with Sister Rosetta Thorpe, Muddy Waters, Sonny Terry and Brownie Magee, and a few others. And they used to commandeer this disused railway station just outside Manchester and turned it into something out of Mississippi. And it might have worked, but it was the middle of winter and all the artists were

So, as far as your question, who’s the typical customer of Document? Well, I’d only had it a few months when I had this strange call from someone who wanted to tell me how much he and his mate loved country blues, all sorts of blues music – it was all me and my mate like this, that and the other, and we love Document. But just at the point when I was thinking, I really must get back to work, he told me that they wanted help with a project – it would involve a book and a TV documentary and a CD. And then he told me his mate was Bill Wyman! So Document ended up doing the album, Bill Wyman’s Blues Odyssey.

And we have now have licensed a lot of stuff to other labels and have licensed stuff for film and advertising and documentaries. And what amazes me is that the requests are very specific, for the most obscure recordings.

And again, with regards to who likes Document? Well, one of them rang me up a couple of years back – and it’s Jack White.

DATC: Yes, this is very interesting. How did this contact come about?

Gary: Well, a couple of years ago Third Manemailed and said Jack White would like to speak to me. So after quite a while, when I had just about forgotten about it, my wife answered the telephone and said, Jack White’s on the phone. So we had this great conversation, talking about what we both were about, talking enthusiastically about the music and so on. And Jack said what an influence Document had been on him and his music from when he was a teenager. Back then he’d walked into a record shop near his home and bought a large number of Document vinyl records, and he gave himself a crash course in vintage country blues.

DATC: So with the Jack White project, you’re doing Charlie Patton, Willie McTell and the Mississippi Sheiks?

Gary: Yes. At first I thought he was going to ask for “best ofs” so I was very surprised that he wanted to commit himself to the whole Document approach of issuing the music in chronological order.

Our ultimate goal was that these LPs would get into the hands of newcomers to the music. We wanted people to look at the covers and then start to listen and then begin to take that journey that we’ve been lucky enough to take. If a young Jack White walks into a record shop and gets interested in this music, then that would be great.

DATC: And the covers of the new albums look absolutely fabulous.

Gary: Yeah. I must admit, when I saw the Patton one at first, I was shocked. But I couldn’t get it out of my head. And now I think they’ve really captured the character of the music.

Gary: Yes! They really did create something of a wow factor when they were first shown.

DATC: So the albums are available on vinyl and download?

Gary: Yeah. At first I thought Jack just wanted to keep it to vinyl. But then he said, if you want to use the artwork for your own CDs, that’s OK. And in the end we agreed that we could use the artwork for downloads from Document.

DATC: How have the LPs sold?

Gary: The albums sold out. The first pressing was 3,000 of each and they sold out within a week. And so the first set of albums are being re-pressed and the second volume is now out. There have been a few delays – with us, and also because Jack never stops – there’s always something going on, with his touring, or films or whatever. I remember saying to his lawyer at an early stage of the project, I can’t imagine this is Jack’s biggest priority, but she said, no you’re absolutely wrong, this is Jack’s main priority. And then she paused and said, but everything that he does is his top priority!

But he’s done so many interviews about Document and banged on about it! So Document has had its moments – the Bill Wyman moment, and another one with Paul Simon – things to keep us interested – but this…it’s not been the same since, it really hasn’t.

DATC: So presumably that has driven the online sales for you as well?

Gary: Oh yeah. It’s been unbelievable. It’s quite interesting – we started our Facebook page in August 2011 and my wife, Gillian, keeps that updated every day. And we were getting 5 or 6 likes a week, but when this collaboration with Third Man came along, we suddenly went up to 2,000 likes. And phones were ringing, people wanted interviews, we started to sell out of CDs. In some ways it was great and in other ways it was quite alarming!

DATC: So the second volumes are now available?

Gary: Yes, they’re available and people can buy them through our websites.

DATC: Thanks so much, it’s been a fascinating conversation!

First published at Down at the Crossroads