How criticism helped the vaudeville: The spotlight on Franklin “Baby” Seals

I have always had a soft spot for persons and events which for whatever reason have fallen out of grace in history books. Often, their story discloses much more of their environment than the historic relics which have been promoted on a pedestal, for the historic aura of the latter testifies more of current than of past values. Likewise, in the history of the pre and early blues the less known is not a fortiori less relevant, on the contrary. There too the fine-tooth combing of extant documents can unveil gems and tell us so much about what went on.

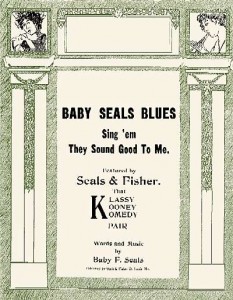

In previous writings, I had the pleasure of bringing the spotlights on vaudeville and blues performers as Butler May and the Whitman Sisters, who have been relegated to footnotes in history despite their tremendous success in the first decades of the twentieth century. In what follows, I would like to indulge in assembling information gathered on another figure, H. Franklin the composer/writer of “Baby Seals’ Blues”, one of the earliest blues songs to be published in sheet music form[1].

I GOT THE BLUES, CAN’T BE SATISFIED TODAY

I got the blues, can’t be satisfied today.

I got them bad, want to lay down and die.

woke up this morning ’bout half past four, Somebody knocking at my door,

I went out to see what it was about, they told me that my honey gal was gone.

I said, Bub that’s bad news, so sing for me them blues.

These was the first verse of the music sheet “Baby Seals’ Blues” published in August 1912 by F.A. Mills Music Publisher[2] in New York, with an arrangement of Artie Matthews[3].

But, before all, let us have a quick glance at the historical context.

1912. In Europe, we were only two years away from the unimaginable horror of the First World War which abruptly stopped the glamorous and frivolous “La Belle Époque”, fed by an explosive growth in welfare and startling technological innovations in the preceding decades. The colonial, unrestrained struggle for power between outdated monarchies and states entailed more than 37 million casualties before it ended in a profoundly redrawn political landscape. In America, the post bellum era had similarly been characterized by an all-encompassing industrialization and mushrooming of big businesses, leading to a nation that played a dominating role in world politics. As in Europe, however, large segments of the population were denied the fruits of this rising welfare and power. The Native Americans, for instance, were in the white expansion to the West more and more relegated – if not yet killed – to reservations. The African Americans had been freed in 1865, but hopes for integration had quickly been smashed to pieces. White America acknowledged the musical genius of the African Americans, but continued to define this artistic expression as a mere marginal feature of an otherwise inferior and barbarous “race”. How illogical could one get? At the end of the 19th century, America was legally segregated, and lynching was a common phenomenon, often taken the form of a spectacle.

Culturally and socially, the turn of the century was one of the most interesting periods ever witnessed. Whilst there was hope that man would be able to conquer the world and nature, there was at the same time an existential doubt on what the future would bring. Industrialization had shaped welfare, but welfare and its concurrent materialism began to be questioned. In Europe, the radical changes inspired also fear and revolt; the concurrent artistic and intellectual query for new forms and expressions laid the basis for later modernism. Perhaps no art work serves as a better icon of this period than Edvard Munch’s 1893 masterpiece “The Scream”.

This cultural turbulence, symbolized by the wide range of artistic movements witnessed in Europe, was largely absent in America, and in many respects, America seemed a bit “dull” in 1912. Certainly, parts of the American population also showed skepticism on the effects of the industrialization, which had been accompanied by a spread of political corruption and growing social inequality. This skepticism was outlined in the Progressive movement of the early 1900’s which sought reform on social, economic and political level, albeit without touching the basic premises of the ruling morality, social hierarchy and racial inequality. However, when it came to its cultural self-definition, America showed no daring innovation.

Lacking a tradition of its own, due to the absence of a common ancestry and legacy, the American middle- and upper class nourished its culture by what it witnessed on the old continent, and filled its European styled houses with artwork coming from the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. The lower classes were enthusiastic consumers of new, yet conservatory, forms of entertainment, of which vaudeville became the most popular. Vaudeville, which popularity boosted in the last decade of the nineteenth century, grouped separate, unrelated acts on a common bill, including popular and classical musicians, dancers, comedians, trained animals, magicians, female and male impersonators, acrobats, illustrated songs, jugglers, …The vaudeville theater integrated also the formerly popular minstrelsy shows which had entertained the public in the first decades after the Civil War. From the 1900’s, black vaudeville theater would also start to blossom, but totally segregated from the white circuit.

Africa too had already left its indelible traces on the American cultural environment. The minstrelsy show’s inspiration had come directly from the white man’s interpretation of the music and dance performed by the African Americans. The staggering success of the jubilee companies exposed the American public (and also abroad) to the fascinating negro spirituals, even if (or, should we say: thanks to the fact that) they had been sweetened and adapted to the popular tastes, leaving only a bleak reminiscence to the unadulterated form that once echoed on the farmer communities and revival camps. The rag time wave that swept over the nation at the turn of the century testified of the same fascination with the African rooted musical idiom, notwithstanding its incorporation of European based harmonic concepts. Today, we associate rag time foremost with the offbeat piano playing by stars like Scott Joplin, made popular again in the 1970’s by the “The Entertainer” theme from the “The Sting” movie. However, at its origins, the piano rag was only a minor part of the scene: all music could be “ragged”, i.e. syncopated. The coon songs were the vocal initiators of the genre that, emerging from the black entertainment scene in “red light” districts, further developed into a stylistic form that transformed popular music in an irresistible dance tune that conquered also the white mainstream musical stage. Its popularity was immense. The sheet music rags were sold by the millions.

PLAY IT SLOW, VERY SLOW

This was the context in which “Baby Seals’ Blues” was published on August 3rd 1912, carrying on its cover the names of Seals & Fisher, “that klassy Kooney Komedy Pair”. More discretely, the sheet indicated at the top, as an instruction for the performers, that the music was to be played “very slow”. The indication is not without significance.

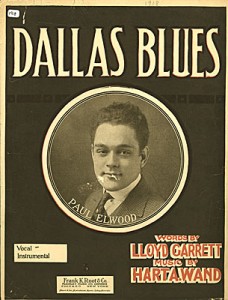

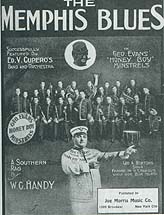

As said, rag was then top of the bill, and “the blues” was not yet a genre that had made its entry in the mass entertainment business. Three years earlier, Robert Hoffman, a white New Orleans pianist had published a piano rag called “I’m Alabama bound”; the word “blues” was however only mentioned in its subtitle “The Alabama blues”, suggesting that the blues was not considered to be an important marketing label (Muir, 2010). This apparently had changed in 1912 when, next to “Baby Seal’s Blues”, four other music sheets were copyrighted with “blues” in their title: Chris Smith’s “The Blues”, Hart A. Wand’s “Dallas Blues”, W.C. Handy’s “The Memphis Blues” and Le Roy Lasses White’s “Nigger Blues”.

Though this commercial breakthrough – if we can use this strong a term already – of “the blues” is significant, it would be misleading to consider the mentioned publications as a stylistic break with the contemporaneous popular music, rag-time. As Abbott and Seroff (2008: 65) noted, “the blues appeared as a transitional mixture of referential jargon and musical riffs derived from folk blues”, and “the 12-bar AAB structure was not yet a rigid consideration.” What distinguished the early published blues songs from the popular rag time melodies was the “markedly retarded tempo.” Contrary to the swinging, catchy tunes of the rag music, the tempo of the blues was “very slow”. Yet, as the same authors highlight, music critics of the time observed that the newly published blues was quite distinctive from the folk blues. A correspondent for the Indianapolis Freeman wrote that the blues, like the one published by Franklin Seals, was of a “clever nature” and “more consciously developed than most blues presentations of the time” (idem, 65).

The early blues music sheet was thus a hybrid form, building on the popularity of the ragtime, but introducing idioms coming from the African American folk blues.

YOU’VE GOT TO SHAKE, RATTLE & ROLL

When Franklin “Baby” Seals published his blues composition in 1912, he was already some years active in business, riding like others on the tide of the rag time wave. Born in Mobile, Alabama[4] , “Baby” Seals is mentioned in the May 8th 1909 edition of the Freeman journal as a pianist in the Lyric Theater in Shreveport, Louisiana. The correspondent noted that “Sunday night we played to 1.964 people, putting on three shows”, featuring “the Perrys, the McGoes and little Rucks, the laughing little fellow, John Ellis and Miss Peal Swingingon”, adding that “Baby Seals is our pianist.” The large audience is already a hint at the talent of Baby Seals, which is confirmed a year later when, in February, the Freeman mentions the publication of a “rag time coon song hit” by a “new composer” carrying as title: “You’ve got to shake, rattle & roll.”

The song is published by Louis Grunewald & Co, a well-established New Orleans company with a tradition of several decades, covering also classical work and popular music as waltzes. The journal adds with enthusiasm: “The song is the first effort of Mr. Seals, and from what we have heard of the piece it is bound to become a winner everywhere it is introduced, especially with minstrel troupes. It has a catchy air and real comic words.” The chorus runs:

“You got to shake, rattle and roll,

Or my money ain’t a-gwine

Now, don’t you think you’ve caught a Gee.

If you do you’re far behin’.

Dis way you guys got squeezin’ dem Dice.

I done told you once, and now I’m tellin you twice,

You got to shake, rattle and roll,

Or my money ain’t a-gwine.”

The same year still, Franklin Seals is performing at the People’s Theater in Houston. The Freeman journal notes in its February 26th edition of 1910: “The Lewis Stock Company has two new additions. Baby F. Seals and Phillip (Daddy) Moore. The show was staged this week by Baby Seals, and he is some producer.”

A mere two months later, Seals is pianist as well as musical director in the Ruby Theater in Galveston (Texas). Though the Freeman journal correspondent notes that Seals is “above the average”, and that “he can put so much juice in your song that you will sing even when you don’t feel like singing”, he focuses mainly on Miss Floyd Fisher, the “dainty little singing and dancing soubrette”. She performed with Elijah (Kid) Davis “in a little skit entitled, “I want some of this, that, those, these, thusly and some more.” Seemingly still enjoying the show, the correspondent concludes: “Baby Floyd and that versatile Davis set the house roaring and couldn’t get away….”

Manifestly, Floyd Fisher’s talent didn’t go unnoticed to Franklin Seals either. In the week of July 25th 1910, both are reported opening at the Arcade, Santa (GA), but again Floyd, then named Baby Floyd Fisher, gets the spotlights when the correspondent calls her the “Doll of Memphis”, who “is a little scream all by herself” (Freeman, August 10th 2010). The duo evidently met with success, and Franklin Seals recognizes overtly the talents of his companion, when in the January 21st 1910 edition of the Freeman, he lauds her in an article he signed himself as “Proo. And Director of Amusement”. He commented on the opening at November 14 1910 by the “Baby F. Beal’s (sic) Bunch of Promoters” at the Bijou Theater in Greenwood Mississippi. The Bijou “Fun Promoters” are a company of 14 performers, but the star is, he wrote, without any doubt Baby Floyd Fisher: “the smallest and sweetest little thing on the stage, singing anything the audience asks for.” “In that way”, he adds, “she holds the house as long as she wants to.”

Clearly, their fame is on the rise, and by the end of 1911, Franklin and Floyd[5] cross the Mason-Dixon Line – symbolically dividing the Northeastern from the South – and are staging in New York, Philadelphia and Chicago[6]. The Freeman edition of December 16th 1911 publishes in his stage section: “Baby F. Seals and Baby Floyd Fisher after filling their engagement at the Family and Lincoln Theaters, New York City, are now playing a return to Philadelphia, Victoria Theater”, adding unambiguously: “Baby Floyd is still the little big favorite.” The type of venues of their performance, such as the Victoria Theater, a luxurious five-story vaudeville house that had opened only recently, and that could accommodate some 1.400 people, suggest again the wide appeal the duo enjoyed.

The publication in August 1912 of “Baby Seals’ Blues”, by Franklin Seals & Floyd Fisher, “that klassy Kooney Komedy Pair, boosted their career even further. The Freeman, in his journal of October 12th 1912, leaves no doubt on this, and prints: “Better known as Baby Seals and Baby Fisher, [they] closed the bill and were a big hit, like the rest of all the hits. Mr. Seals is a known favorite of the Crown garden. He offered its patrons a new act of fun, which was a laugh from the start to the finish. Miss Fisher in her male impersonation is very clever. Mr. Seals’ original songs which were being sold last week at each performance, I notice, are still being called for by those who could not get them last week. Seals and Fisher will always be welcome at the Crown Garden (…)”.

Hence, the music sheet seemed to sell very well. Seals and Fisher struck, by the way, a deal with the Freeman to use the journal as a basis for mail order distribution (Abbott and Seroff, 2008: 65), and advertisements for the music sheet regularly appeared on its pages.

A further indication of the song’s success is the observation that it was integrated in the vaudeville repertory of other performers. Abbott and Seroff found sufficient leads in the Freeman journal that Baby Seals” Blues “found special favor with fellow southern vaudevillians” (p. 63), quoting among others Daddy Jenkins and Little Creole Pet, accompanied by Jelly Roll Morton, Edna Benbow Hicks, Laura Smith and Charles Anderson. The latter, active in vaudeville since 1909, was better known as the yodeling blues singer. In 1913, a St. Louis review describes him as “The Male Mockingbird”, “the man with the golden voice” [7]. He performed extensively for both black and white audiences. In 1923, Charles Anderson would wax “Baby Seals’ Blues” as “Sing’ Em Blues.”

Furthermore, the song was already in November 1912 adapted to a band arrangement, and a trombonist, Frank Terry, made “a daily hit with it” (Lynn and Abbott, 2007, p. 177). The wide dissemination of the song was finally guaranteed by its integration in the repertory of circus side show annex bands, which covered the whole nation, up to the remotest, rural communities.

From what precedes, the conclusion is evident, that Franklin Baby Seals had by 1913 firmly established his reputation as a comedian, pianist and composer. But what is most relevant, was that when in 1913 he was inducted to the Richmond “Order of the Elks”[8], he was identified as the “Famous Blues Writer.” His vaudeville reputation was thus no longer associated with rag time music, the genre he debuted with, but with “blues”. It is evidence that in the past four years since he wrote his “rag time coon song hit” “You’ve got to shake, rattle & roll”, quite a development had taken place in the popularity of the blues genre.

Seals’ success was however of short duration. He died on December 29, 1915 in Anniston, Alabama[9].

Quite comprehensibly, at this point, the name Butler May “String Beans” pops up in our mind. Like Franklin Seals, he made a startling career in the vaudeville theater, rising around the same time from the local Southern theaters to the “grand’ theaters above the Mason-Dixon Line. Franklin Seals teamed up with Floyd Sister; Butler May shared his success with Sweetie Matthews ( Bosman, 2012). Butler May dies in 1917 when an initiation rite in the Jacksonville Freemason lodge went out of control. It is tempting to speculate what might have happened when both men had lived to enter the recording studios in the 1920s….I leave, however, this exercise for you to do. Let me conclude with some general considerations.

“PREACH ‘EM BLUES”

In Mach 1927, Bessie Smith recorded for Columbia her version of “Baby Seals’ Blues” under the title of “Preaching the Blues” (b-side to “Back-Water Blues”). While in the original version, the verse sounded:

Sing-em, sing-em

Sing them blues,

‘Cause they cert’ly sound good to me

I’ve been in love the last three weeks

And it cert’ly is a misery

Bessie Smith’s version was slightly adapted to:

Preach’em blues

Sing them blues

They certainly sound good to me

I’ve been in love for the last six months

And ain’t done worrying yet

During 15 years, not much had been changed, proving the innovative character of Franklin Seals’ blues composition when it was published. But what had made it possible, at the start of the 1910’s to allow this song in particular and the blues in general to rise to popularity in such a short period?

I believe that four evolutions and situations are a lead to a tentative answer: commercialization, black vaudeville, the enormous pool of black music talent and the fascination of white with the African American music.

The industrialization, carried by a blistering technological evolution and the enormous possibilities for geographical mobility went hand in hand with an increased, nationwide appetite for (mass) entertainment. In the early years after the Civil War, minstrelsy had risen to be the first entertainment industry, but in scale it could not be compared to the entertainment business that mushroomed at the end of the century based mainly on vaudeville, music sheet publishing houses, circus shows, and last but not least, the booming recording business. Not later than 1889, when a coin-operated Edison cylinder phonograph was installed for the first time, started a rage of coin-in-the-slot phonographs installed in public places. By 1895, recorded music as a medium of entertainment was firmly established with the public. Music had become just another commercial commodity.

Black vaudeville as an entertainment format struck a chord with the entertainment needs of the African American population from the early 1900’s. Urbanization had engendered an entertainment hungry market in the cities, flooded with uprooted black people who wanted to hear their own music. This music needed to help them in sustaining with pride their own identity in a society that had legally segregated them from social, political, economic and cultural life. The parallel development of an entertainment structure in the form of black vaudeville that offered a platform for the abundant, musical talent within the African American population was at the same time a school where this talent could further extend and deepen its professional experience.

When Dvorak in 1893 contended that “In the Negro melodies of America [he] discover[ed] all that is needed for a great and noble school of music”, he was merely confirming the white fascination with black music and dance that already had nurtured the success of the minstrelsy. The coon songs which ignited the rag time craze were a further illustration.

Though the immense popularity of rag time music was too a result of America’s entertainment sector looking at the European standards of harmony and melody, it drew – more importantly – the main stream attention to other black musical expressions than the popular Negro spirituals. The jubilee companies had, in the immediate post bellum era, convinced the public, both in America and abroad, of the wealth of expression embedded in the black spirituals. Scholars had, in parallel, observed the scant extant documentation on secular black folk music. Thus, in a way, “ragged” music, with its roots in the poor, black neighborhoods, was the evidence that black musical expression clearly reached beyond the sacred songs popularized by the jubilee companies, and investigated by the new folk lore academic discipline. The style, moreover, immediately fused the enthusiasm of the wide public. The mood created by rag music was perfectly in harmony with the joyful time spirit and with the demand for entertainment. It was no coincidence that the 1893 Chicago World Fair was the first to have an area completely dedicated to entertainment. Technology and progress were the Fair’s key ingredients. Rag time music fitted the picture perfectly.

Rag and its tempo also matched the pace of the white and black vaudeville format. Coming from brothels, ragged music made its grand entry on the vaudeville stage. No act was complete if rag music was no part of it, and hundreds of composers, of all levels of talent, white and black, submitted their compositions to the publisher companies.

Rag and black vaudeville thus helped the blues to acquire the status of popular music. With compositions like “Baby Seals’ Blues” and others, the blues idiom, though not yet in the strict 12-bar format, found its way to the 1910′s performance stages, both black and white. The blues conquered between 1912, when it was first published, and 1920, when it was first recorded, a firm place in the mainstream vaudeville (Muir, 2010). While in 1909, Robert Hoffman’s “I’m Alabama bound” carried the word “blues” only in its subtitle, by 1920 “blues” had become a widespread phenomenon on Broadway.

In turn, the 1910’s rising popularity of the blues on the performance stage and on music sheets, provided the fertile soil for the flourishing of the commercial recordings of blues in the 1920’s.

It is in this context that I measure the role played by Franklin Seals. His historic renown mainly derives from his famous 1912 composition, but this is a one sided, incomplete picture. “Baby” Seals is grossly underestimated as a live artist on the vaudeville stage, and the articles in the Indianapolis Freeman provide ample evidence of his talent as pianist, comedian, and producer, even if it was frequently his female partner, the Memphis Doll, Floyd Fisher, who stole the show.

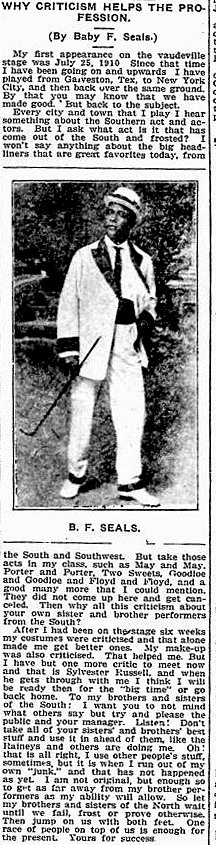

Besides, Franklin Seals was an active promoter of black music, as witnessed by an open letter he sent to the Freeman, published on January 13th 1912. Titled: “Why criticism helps the profession“, the letter is addressed to the critics, among his “own black brothers and sisters”, of the Southern performers when they go up North. His advice to his fellow artists confronted with the often cold initial reception by Northern theatrical critics is to follow only the wishes and guidelines from the manager and the public. Criticism should not hamper the entertainer, on the contrary, he should learn from it. All the criticism had helped him, he confided to the reader, to become a better artist. He concludes: “So let my brothers and sisters of the North wait until we fail, frost or prove otherwise. Then jump on us with both feet. One race of people on top of us is enough for the present.” Signed: “Yours for success”.

Franklin Seals was thus much more than just the composer of one of the first published blues compositions; in the same league as “Stringbeans” Butler May, he made it on the national vaudeville stage as a beloved performer who substantially contributed to paving the way for the popular recorded blues to rise only a few years after his death. But he needs to be remembered, finally, also as the spokesman for the Southern entertainers who sought success up North. He was convinced of the richness of what African American culture had to offer to the whole nation, and strongly invited his “brothers and sisters” to persevere, as he did, and “not to mind what others say.”

°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°

READING

– http://www.perfessorbill.com/pbmidi2.shtml

– http://www.theusaonline.com/history/industrialization.htm

– http://lcweb2.loc.gov/diglib/ihas/loc.natlib.ihas.200035811/default.html

– http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ma02/easton/vaudeville/vaudevillemain.html

– http://www.soc.duke.edu/~s142tm01/history.html

– Peter C. Muir, Long Lost Blues, 2010

– Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff, They’ Cert’ly Sound Good to me, in: David Evans, Ramblin’ on my mind, 2008

– Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff, Out of Sight, 2002

– Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff, Ragged but Right, 2007

– Marshall and Stearns, Frontiers of Humor: American vernacular dance, 1966

°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°

FOOTNOTES

[1] Acknowledgements go to Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff :”They Cert’ly Sound Good to me”, in : “Ramblin’ on my mind”, David Evans (ed.), 2008, and Peter Muir, “Long Lost Blues”, 2010. Credits go also to Google that allows browsing through the archives of the Indianapolis Freeman from the desk office at home. The presentation of the data here is of course my own responsibility.

[2] Kerry Mills (1869 – 1948) an American composer of popular music during the Tin Pan Alley era whose production covered diverse music ranging from ragtime, to cakewalk and marches. Trained as a violinist, Mills had moved to New York City in 1895 where he started his music publishing firm, F. A. Mills Music Publisher, which output was Mills’ own music and that of others. One of the latter was this music sheet, titled “Baby Seals’ Blues”

[3] I have long hesitated to dedicate part of this essay to Artie Matthews, a name too often forgotten when quoting Baby Seals’ Blues. My eventual footnoting his name here does not involve an appreciation of his talent. On the contrary, I feel very much tempted to investigate his person in a separate essay. Let it suffice here to mention that Artie Matthews (1888-1958) was a very talented songwriter, pianist and ragtime composer. He is ranked, with Scott Joplin, as one of the finest rag time composers. His “Weary Blues”, composed in 1915, would also become a standard American song. In 1921, Matthews and his wife established the “Cosmopolitan School of Music”, the first black owned and operated music conservatory in the U.S. For the next thirty-seven years, Matthews provided exposure, training, and education for hundreds of African Americans desiring knowledge and/or careers in music (http://www.matraproductions.com/dadspage.htm).

[4] I have not been able to trace his year of birth.

[5] The man-wife act was the best-paid act on the black vaudeville circuit; it allowed the comedians to develop an act that pointed to the husband-wife conflict, very recognizable for the public.

[6] Let us recall that it was in May 1911 that String Beans, then staging with Sweetie, made his historical crossing of the “Mason-Dixon line” (Bosman, 1912).

[7] Quoted in: http://www.mustrad.org.uk/articles/b_yodel.htm. Charles Anderson is said to be also the first who professionally performed the “St. Louis Blues.” (http://www.americansongwriter.com/2009/07/behind-the-song-st-louis-blues/)

[8] The Order of the Elks is a nationwide American fraternal order and benevolent social club, founded in 1868, and which are said to count about 1 million members. In its origin a private white organisation, in 1898 a black and unaffiliated organization was formed. It is organized in local “lodges”.

[9] I have not been able to trace information on the cause of death.

Source: www.myblues.eu/blog

Erwin Bosman

Read the print-friendly document here