From lash to cash: one step on the path to the blues

From : www.myblues.eu

The lineage of the blues to the African-American slave field hollers, work songs and spirituals has been endlessly repeated. Plenty of historical overviews highlight how these vocal articulations echoed African cultural elements, and how their characteristics have had a defining impact on the development of the blues. It is safe to say that, if Africans had not been captivated and set to work as mere ‘chattel property’ by Euro-American colonists, Western musical history would have sounded very differently. The ‘sounds of slaves’ in the American colonial context have set in motion a cultural development that, at the end of the day, culminated in what I believe to be one of the most impressive and expressive forms of American, and Western, art. Yet, a correct understanding of the mechanisms involved in the transformation of African modes of expression to a new American musical genre, requires foremost recognition that a particular historical American context was crucial to this “re-creation”. It is important to realize that the American context, where the sound of the slaves reverberated over the fields, was an economic enterprise built upon white owned land and black labour, the latter not even being considered of a ‘human’ nature. When the black labour was transported to the British colonies, there was no other motive at stake than to make the land profitable, this is: to extract the cash from the crop. What other motive or prospective vision was needed? After all, the African ‘merchandise’ had no higher status than the hogs, cows or mules on the farm.

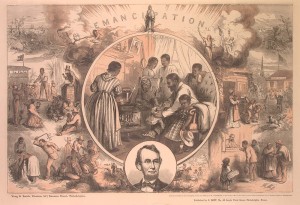

The recognition of this basic context is indispensable to follow the path to the blues, but it is only the starting point. We need to look in more detail into the fascinating way the history, in America, of these people from various African origins has been intertwined with the history of the global American society. It is crucial to examine how the common historical path of black and white has finally given birth to a truly creative, original and authentic musical culture, born at the bottom of society. In what follows, I pause at one milestone along this path: the change of status from slave to ‘freedman’. The Emancipation and its formal enactment in the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which officially outlawed slavery and involuntary servitude, has been a major historic event which changed the global existential context of the African American, and by this influenced his musical expression.

One cannot appreciate the Emancipation’s full significance, however, without first taking a few steps back along the path.On this way back, I mainly draw from the insights of LeRoi Jones and Lawrence W. Levine as a historical guides.

Many historical narratives confine their story to the physical hardship of the inhumane handling of the Africans who had managed to survive the even harder conditions of the Middle Passage. The cruelty inflicted on the captivated Africans has been rather well documented. LeRoi Jones sees more, however, than the mere physical and emotional suffering. What is essential to the comprehension of the core of African captivity in the American colony is the observation that, not only the slaves were defined as non-human, but most importantly, that they were dropped in a culture that was the complete opposite of their own.The American colonial culture was the expression of a Western view on the world, a view that was economic and secular. Next to the want for escaping the European continent for whatever reason, the main motive for settlement in the colony was the accumulation of wealth and profit. It was a pure secular motive that drove the colonists across the Atlantic Ocean, at least for most of them with a Protestant background. The African, by contrast, originated from a culture where the divine and spiritual occupied a central place. The African belief in a supernatural cosmos was the opposite of the ‘humanist’ definition of man and nature that had evolved from the European Renaissance. For the American colonist with a ‘humanist’ world vision, the only way to face the foreign culture was to ignore that it existed, or even could exist: the slave was not more than an item in his accounts. It was impossible for this ‘item’ to have a culture! For the African slave, however, the comprehension of the basics of the white culture was a component of the survival strategy in an environment that, upon the first arrival, most certainly must have been agonizing, strange and unnatural. It was essential for him to understand what the white man expected from him. He had to make himself familiar with the fundamental notions and vocabulary of his owner, if it were only to avoid the whip.

Contrary to the plantation system in the West-Indies, and later in the rice fields of the American South-eastern coastal regions, the first slaves who arrived in the Upper South to toil on the Virginia tobacco fields had a rather direct contact with their white owner. The size of the tobacco farm was, compared to the rice, and later cotton and sugar plantations, relatively small. Moreover, the owner himself pulled the strings and ruled as a ‘father of the family’ over his estate, as he would run his family domain in his homeland. His paternalistic approach required his factual presence to see to it that his black property correctly followed his instructions. Within this model of social and work organisation, the black and white physical contact was close. Furthermore, the tobacco crop was a very delicate one that imposed a rigorous and constant care, which explains why slaves’ work was organized according to the gang system. Unlike the task system which set the slaves a particular work goal to meet, leaving him some autonomy during the rest of the day, the gang system imposed a continuous work at the same pace throughout the day. Indirectly, this division of labour had also its impact on the very short, if any, period that women were allowed to care for their children. As the elderly were not always and readily available, it was not uncommon on the smaller plantations to see white and black children running around and playing together. Interracial contact started at an early age.

While Africa was still the homeland for the first generations of slaves, after some decades the only reference to Africa that remained was the one contained in the stories told by the elder slaves. In this new generations’ frame of reference, Africa had become more and more a foreign land. The African was slowly becoming an African-American who had learned how to interpret the white man’s cultural symbols, while developing through his creativity and flexibility different ways of adaptinghis own modes of expression to cope with his new environment. The European-centric attitudes gradually filtered into his African outlook.

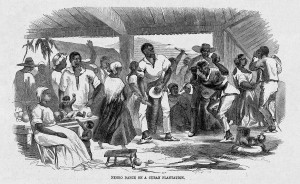

Yet, it is essential to emphasize that core non-material elements of the African culture, such as the slaves’ spiritual beliefs expressed through music and dance, were not eradicated by their new cultural world. Of course, the context in which their music and dance evolved was different from what existed in their earlier homeland. Therefore, the music and dance of the ‘Negro’ could impossibly keep the same content in a society where his labour and its products were not his own, and where the white planter defined the perimeter of what was allowed. Though generalisations always obscure local particularities, it is safe to say that for most of the slaves in the American colonies this integration in the ‘New World’ took the form of acculturation. By this, I mean that the slaves slowly transformed their African traditions into new forms which were more functional to the altered context. While holding on to their fundamental values, they re-created them to fit their state of submission in a strategy to deal with it. This re-inventionof their African traditions was, I believe, a matter of pure (psychological and often also physical) survival. It allowed them to keep their dignity and self-respect, and thus their human identity even if they were considered as a mere accounting item, replaceable at any moment. The acculturation was noticeable in different areas. For instance, it showed in the storytelling. Storytelling was one of the commodities slaves brought with them from Africa even “if stripped of all clothing and personal possessions during the Middle Passage” (Stephen Doster).

One example of a story that represents a re-creation of an ancient African lore is the popular “Bruh Rabbit”, or “Brother Rabbit”, the archetype of the popular (Southern) American trickster character who succeeds by his wits rather than by his strength and power, to make fun of authority figures, and who bends social values to his own ends. The “Bruh Rabbit” tales flourished during slavery, and almost always narrated the story of the weak involved in an endless contest with the strong. One could interpret this story cycle as a slave expression of subversive sentiments against the institution of slavery. Indeed, since it was way too risky for slaves to show explicitly to their owners the harsh cruelties of slavery, they vented some of their frustrations and hostilities by participating in the performance of the “Bruh Rabbit” tales. The analogy with two major African tricksters figures, Anansi, a spider and Ijapa, a turtle, is more than a coincidence (1). The story’s African origin and spirit remained, but were transformed into a cultural tool that was highly functional in the context of slavery. The story inspired how to survive under the rule of the strong, but by its repetition made it also clear that only battles could be won, not the war (Lawrence Levine, 1977).

A similar process happened in the musical expression. It is no surprise that the work related songs were the first to be more or less stripped from their African ritual color. After all, the use of their labor was the primary reason Africans had been bought and had been put on the boat to America. Obviously, the work songs and field hollers, after some time, needed to change their content as the fundamental, I dare even say: the existential characteristics of their work had changed. Back in Africa, the cultivation of ground and related activities were directly instrumental to the life support of the tribe. Work and music were, in the African homeland, closely intertwined as essential components of a communal existence. In America, the plantation labour was forcedlabor for the sole benefit of another. They worked on a foreign land that was not their own. Moreover, it was no longer possible, or even dangerous, to make direct references to the African gods and spirits, as most of the planters simply did not allow this. The ‘secular’ music was thus the first to be subject to ‘re-invention’ and acculturation. The worship of African gods and spirits could continue, but then only ‘underground’, in the woods, sufficiently remote from the planter’s ears and eyes.

As LeRoi Jones convincingly argues, there was thus a significant change between the first and later generations of slaves. The first slaves had an African frame of reference. The American born slaves, on the contrary, only had the slaves themselves as a reference group. The new work songs became a direct reflection of a context shaped by people who had an opposite world view, and who had the power to dictate what was allowed or not. As a result, the secular music of the American born slaves was gradually infused with the local vocabulary relevant to their new existential context, and supportive for their survival. It contained references to activities foreign to their African origin.

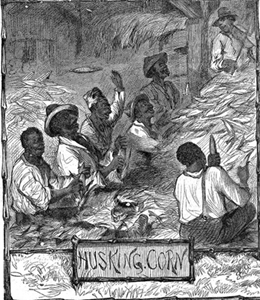

An illustration to this is “Shock along, John“, one of the few secular songs noted in “Slave Songs of the United States” (1867), that refers to the corn husking on the plantations:

“Five can’t ketch me and ten can’t hold me

Ho, round the corn, Sally!

Here’s your iggle-quarter and here’s your count-aquils

Ho, round the corn, Sally!

I can bank, ‘ginny bank, ‘ginny bank the weaver

Ho, round the corn, Sally!”

However, the traditional African music and dance showed their resiliency: the carry-over of Euro-American elements only happened at the outside. It was, at the end of the day, only a thin layer of Euro-American camouflage. This observation is essential to understand how the path would lead to the blues. The slave population integrated European elements in its music and dance, but these were cast in an African grammatical mold. The basic African characteristics, particular (multi)rhythms, the polyphonic voices and the use of call-and-response, remained intact. The black population retained its sense for extremely fine and complex rhythms, and not to forget: its creativity in improvisation, which is “probably the strongest survival in American Negro music” (LeRoi Jones). Finally, their music continued to be directly functional, contrary to the European concept where music is a form of art, not integrated in the daily functioning.

On their African character, L. McKim, co-author of “Slave Songs of the United States” notes:

“It is difficult to express the entire character of these negro ballads by mere musical notes and signs. The odd turns made in the throat and the curious rhythmic effect produced by single voices chiming in at different regular intervals seem almost as impossible to place on the score as the singing of birds or the tones of an aeolian harp.”

In his majestic study of Afro-American folk songs, H.E. Krebhiel (1914) writes that it is not a surprise that “there should be resemblances between some of the songs sung by the American blacks and popular songs of other origin” (referring to the white folk songs). Yet, he underlines at the same time how the slave songs were far from being copies, when he quotes W.F. Allen, main author of “Slave Songs of the United States”: “In the main it appears to be original in the best sense of the word, and the more we examine the subject, the more genuine it appears to be.”

The movement away from Africa by the American born slaves thus implied a cultural adaptation marked by a continuation of African characteristics that, combined with references to their ‘new world’, resulted in originalforms of expression.

The Christianizing that started to work at full strength among the slave population from the first decades of the nineteenth Century was a further step in the process of drifting away from Africa. With the conversion, Africa became even more a ‘foreign’ place. However, as was the case with the storytelling and the secular music, the way the European religious values and worship practices entered in the slaves’ life took a definite African form and culminated in something new.

The conversion process cannot be understood without considering the central role of dance and music in the African life. They were indispensable in the development of the Afro-American religion. “In Africa, ritual dances and songs were integral parts of African religious observances”, notes LeRoi Jones. The emotionalism in dance and song, crucial to any discussion of the black church, explains why foremost Baptist and Methodist denominations, with their strong emotional emphasis, appealed to the slave population. Contrary to the classic Calvinist puritanism that “greatly prized the control of affect” (Milan Zafirovski), the Baptists and Methodists could more easily seduce the black population. Moreover, the story of the oppressed people of the Jews that were brought to the Promised Land of freedom, to the Jordan, “the garden of God”, tickled the slaves’ fantasy, and brought along dreams of a place where they no longer would suffer from bondage. From this confrontation of African culture with especially the Baptist and Methodist churches resulted a new Afro-American religion, a form of Christianity that was experienced in a practical way that was essentially African derived in lyrics, rhythms and harmonies. Only the superficial forms were Western.

As James Abbington expresses it in his “Readings in African American Church music and worship” (2001, 482): the Negro Spiritual “was a uniquely African response to an institution that waged a systematic, though unsuccessful, onslaught onto the cultural legacy of the Black people in America. When introduced to Christianity, African slaves reinterpreted their religious instruction through an African cultural lens.” James Weldon Johnson and John Rosamond Johnson (1925) are clear in their statement that the spirituals, together with the secular songs give a full expression of the life and thought of the “Negro race” (sic) in the United States. The originality of this expression is also unambiguously demonstrated by D.K. Wilgus (1990): “It is perhaps the interpretation of the Negro spirituals in the light of the American history and in the context of American Negro life in the United States which must take precedence over questions of European versus African origins. In that sense, American Negro folklore should never be considered European folklore or African folklore. Rather it is, simply stated, American Negro folklore!” (67) The meeting of the religious music of the two cultures produced elements that were later used in the secular, blues music.

The path from the slaves’ music to the blues music, however, wended through the experience of the Emancipation and the (short) period of Reconstruction.It is impossible to “place” all the characteristics of the blues without assessing the significance of this period for the African-American.

When on December 6, 1865 the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution officially outlawed slavery and involuntary servitude, all slaves could echo the joy of their South Carolina fellow: “The Master he says were are all free” (Paul S. Boyer et al., 2011). However, as later developments would confirm, it testified of a high sense of realism of this slave, when he added immediately: “But it don’t mean we is white. And it don’t mean we is equal.” Notwithstanding the efforts and ideals of the abolitionists, the formal stop of the Reconstruction no longer than 12 years after the signature of the Thirteenth amendment painfully demonstrated that the freeing of the African American populace had not been the main goal of the Civil War, but rather an element in a political strategy that could, as any, be reduced to a struggle for economic power. A struggle among the white. For the slave population, at the end of the day, the Emancipation was a step from “lash to cash” (E.C. Royce, 1993). The rule by the whip of the planter was replaced by the dictate of the need for cash, indispensable for his upkeep. The failure of the attempt to assign the freedmen an “emancipated” place in society through the policy of “40 acres and a mule”ended up in a situation where the iron shackles were replaced by those of a total financial and economic dependency in the form of the share-cropping and tenancy system.

Yet, we can never underestimate the impact of the Emancipation on the social and cultural experience of the enslaved, and thus on their music which is a direct reflection of this experience. Typically, in the antebellum, a slave’s life was confined to the plantation. His frame of reference was made up of the master and his family, and of the other slaves on the plantation. When you would ask a slave about his plans, he would be puzzled by the question. Being a slave was the beginning and the end. The fence of the plantation was also geographically his horizon, except for the short journeys granted by his owner and regulated by a system of travel passes. The most fundamental change in his life, was the hiring or selling to another plantation, which was as geographically and socially restricted as the previous one. In a cruel sense, this made the slave an integral part of the society. His social position was clearly defined and, moreover, he did not even have to worry how to care for his livelihood. The allowance system provided him with food and clothing, no matter how basic they were. In this configuration, the slave was not only forbidden, as a rule, to keep money, he did not even need it.

When you would ask a freedman after the Emancipation for his plans, the answer would be more difficult for him to give. There were now several options and he could at least have the impression of being in control of their realisation. All that he was able to produce, could potentially be his own. He had the right to his own labour, and he had a never experienced sense of autonomy. The barriers that before limited his life, both geographically and socially, had all been broken down. The fence was on the ground. At least theoretically, the whole society was potentially his group of reference. This was no more and no less than an earthquake in his life, an existential revolution. Africa as a homeland was never further away.

Simultaneously, as LeRoi Jones observes, the African-American stood however further away also from the “mainstream” American society. As stated above, under slavery, the African-American had a clearly defined place in society. The Emancipation had been enacted without at the same time offering a clear definition of what the freedman’s place in the new society was to be. He was in no man’s land, with empty hands: no property, no tools, no capital, only few skills and dominantly illiterate. It was however in this no man’s land that “the negro’s music lost a great many of the more superficial forms it had borrowed from the white man, and [that] the forms that we recognize now as blues began to appear” (LeRoi Jones, 59). In a few years after the Emancipation, the shouts, the work songs, the field hollers, yells and spirituals became to take shape as primitive blues. The reference frame that before nourished the black music and dance was no longer valid and relevant. Which were the major changes that turned out to be essential for the blues?

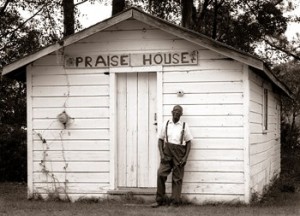

– In the antebellum years, the praise houseswere a major gathering place where slaves could enjoy their religious and musical activities. Other than ‘underground’ dancing and music making and the owner organised or tolerated entertainment, such as during corn husking or Christmas, there were few other places or other occasions where the blacks could, in a relative way, feel a bit of spiritual freedom, or could enjoy any kind of “vaguely human activity” (LeRoi Jones, 48). Praise houses were small buildings, located near the slave quarters, that the owner allowed his slaves to construct to hold worships throughout the week and not only on Sundays. They were built as a supplement to the church services organized and controlled by the planter. “The praise house offered slaves opportunities to escape the white gaze, challenge white authority, sustain community and culture, and reinvent the Christianity they were taught to conform with their lives and experiences” (Martha B. Katz-Hyman, Kym S. Rice, 2011).

As a result of the Emancipation, the praise house lost its near exclusivity as an accepted meeting place for expressing music and venting frustration against the white. LeRoi Jones (48): “During the time of the slavery, the black churches had almost no competition for the Negro’s time. After he had worked in the fields, there was no place to go for any semblance of social intercourse but the praise houses. It was not until well after the Emancipation that the Negro had much secular life at all.”

– As a correlative development, the Jordan, previously conceived as a biblical land of freedom, a dream, gradually acquired a more social and personal dimension. Freedom was no longer a theoretical, spiritual concept but a tangible aspect of real life, a life that was open to (material) improvement. The Promised Land was an objective that was to be realised if not during one’s own live, than at least for the future generations. There was a reasonable and understandable hope that the black population could start to cross the Jordan River in a victory over their slavery. Obviously, this secularizationof ideals affected the musical expression.

– The Emancipation, the legal freeing of the slave, also meant a suppression of forced labor. The African-American, for the first time in his life, in principle gained autonomy in the use of his own labour labor and its products. If we make abstraction from compulsions to which free laborers are subjected, forced labor made the way for free labor. For many, the very notion of black “free labor” had been, and at that time still was a contradiction in itself. Black labour was often by definition considered as forced labor. Anthony Trollope, one of the most successful English novelists wrote in the 1860′s: “[The Negro] is capable of the hardest bodily work, and that probably with less bodily pain than men of any other race; but he is idle, unambitious as to worldly position, sensual, and content with little…. I think that he seldom understands the purpose of industry, the objects of truth, or the results of honesty. [The blacks] are a servile race, fitted by nature for the hardest physical work, and apparently at present fitted for little else.” (quoted in: James Walvin, 1992).

– With the suppression of forced labor came also the suppression of the allowance system that guaranteed a minimum livelihood for the slave. Instead of it, the freedman after Emancipation had the obligation to make a living for his own. At the same time, however, this new economic necessity was accompanied with the disposal of free timethat was left after working hours. The possibility to fill in time for himself, outside the control of the planter, outside also of the grip of the religion and the praise house, was a brand new facet in his life, never experience before. Though during slavery leisure activities have been documented (Stephen Doster), they were firmly embedded in the plantation’s life and under strict regulation by the planter. The Emancipation from forced labour, meant simultaneously that there was room for an autonomously organised leisure time, which is yet a new contextual element that could not remain without effect on music and dance.

– Mobilitywas often liberty’s first fruit (Boyer et al.). The plantation fences were brought down and the slaves could leave their quarters and the plantation. Waves of migration rolled over the South, steered by the search for higher wages paid in the Deep South, the attraction of jobs in town or city, or simply by the look for lost relatives and the desire for family reunion.

Inherently attached to migration was the confrontation with new stories and ideas. The reference and peer group became much more extended than they had ever been before. On the musical level, the mobility created the possibility to learn about other songs and to acquire each other’s techniques and skills of singing and playing. It acted also as a kind of selection mechanism that worked as a filter for promoting the best verses and techniques. In this sense, the mobility contributed to an inter-regional standardization.

– The cash had replaced the lash, but cash was to be worked for. The economic security, once provided by the planter, became dependent on the possession of money. One way of earning money, several African-Americans realised, was to go on stage and perform music as source of livelihood. Though as early as the 1850s black minstrel groups appeared already on scene, it was understandably only after the Civil War that there were serious attempts to exploit the talents of black entertainers to put them on the commercial stage (A. Bean et.al, 1996). Black minstrelsy became popular. Largely white owned and managed, there were however notable exceptions of black directorship that were popular.

– The complex of the above circumstances entailed, or at least rendered possible, what can be called a thematic liberation. The legal freedom, and the freedom of labour, mobility and the possibility to organize one’s own life dramatically changed the social and cultural environment of the former slaves. Their environment was no longer restricted to the farm, but encompassed in principle the whole American society, which inevitably found its articulation in new feelings, hopes and dreams that nurtured their music and dance. While as a slave the song was meant to accompany work that was not his own, and/or was a device by which he could comment on his owner’s cruelty in a language that the latter did not understand, the Emancipation offered a totally new array of themes which lent itself for a creative, autonomous expression. The subject of the songs could be extended to, in principle, all themes the performer considered important, unlimited also by religious considerations.

What conclusions do I draw from the above observations?

I strongly belief that the Emancipation is of utmost importance for the understanding of the development of the blues music both as a very specific historical event with its own particular consequences, and as an illustration of a more general observationrelated to the dynamics of black music.

As a specific historical event, it created a new environment that made it possible for black musical expression to take some characteristics that would later be essential for the genre that we now call the blues. The strengthening of secularisation, the liberation from the praise houses, the geographical mobility, the possibility for musical expression in an autonomously arranged leisure time, next to the thematic liberation and the choice to earn a living from music now all seem obvious, but were a direct or indirect result of the Emancipation. At the same time, the individual dimension in the expression gained in importance. It became possible for a man (or woman) to sing or play by him(her)self, wording his/her own life experiences, hopes, failures and successes. Music was no longer an exclusive communal act. The concept of ‘solo’, the expression of the individuality, basically foreign to African culture, was introduced.

These were the factual prerequisites for the development of the blues. However, the fascinating part of the whole story, which also makes up the strength and appeal of black music in general, and blues in particular, becomes only visible when we take our view to this historical development at a higher level.

Alan Lomax has argued that “musical style” is one of the most conservative traits in a culture, which appears to change more slowly than any other human art. By “musical style”, he refers to the basic color of a music that symbolizes a fundamental social-psychological pattern, common to a culture. It reflects fundamental human values and human experiences. The African style is one category of a limited number that exist in the world. This certainly explains why, despite the pressure of the ‘white’ culture, the slaves held on to their typical African musical idioms such as poly-rhythm, anti-phony and improvisation. Only the outer layer of the “slave sounds” reflected the white controlled reality. The mold of the music and dance remained African.

We notice a similar phenomenon as a result of the Emancipation. On the one hand, the formal expression of the music remains African, non-Western. On the other hand, there is a further drifting away from the African homeland towards mainstream American in the thematic choices and in the way that music is brought. Contrary to the African tradition, black music became a music that could be sung for pleasure, for pure entertainment, and to make a living.

Thus, in a sense, the black music after Emancipation was subject to two contradictory, opposite pressures. The first one confirmed and strengthened the formal African style since, by leaving the plantation, the restriction imposed by the white on the African-American to express freely his ‘weird’ style also disappeared. The second one pushed in the direction of the American mainstream. The latter was by the way also visible in the language that was used. By the time of the Emancipation the knowledge of the English language among African-Americas was sufficiently spread, and the use of it deemed necessary if the performer wanted to convey his message to as large a public as possible. Also, in the use of instruments, there was a growing mainstream impact. Unlike the work songs, field hollers, and the spirituals, the new black music was no longer opposed to accompaniment by instruments from a European origin, such as the guitar. Though instruments were mainly used as emulation and reinforcement of the voice, there was a movement from the pure vocal music, central in the African musical style, to music where the instrument was taken into consideration as part of the larger act.

I am convinced that the power of the blues largely comes from the dynamic forces released by those opposite movements. It is from the unique combination of seemingly incompatible African elements with cultural traits created by the very specific American context in which the black population struggled for survival that welled up a new musical genre. If we accept this observation, we also can found a way out of the continuous debate on whether the blues is African. They are, but not in a static way. We simply cannot ignore the lively evolution, during more than two centuries preceding the first registered blues expressions, of an African culture that manifested its resiliency through its capacity to adapt itself to new environments, and yet to reconfirm, time after time, its identity. The changing historical context offered again and again new elements that were creatively integrated in a musical style that remained essentially African and did not fall for the seducing sounds of the sirens of mainstream music.

It is fundamental, in other words, that we define culture not as a static phenomenon but as an ongoing process. This awareness lets us see that black music has been able to re-invent itself each time when the social position of its performer changed. A constant component of this re-creation was the innovative way in which the music and dance offered the effective instruments to cope with an oppressive system, in whatever form. Even when music became a form of entertainment, it retained its basic function to offer for both the performer and its (participating) audience the outlook on ‘something better’. The despair and tragedy of a song did not exclude the hope: “Trouble in mind, I’m blue but I won’t be blue always. For the sun will shine in my back-door some-day” (R.M. Jones).

In this dynamic perspective, it is also more difficult to define the “roots” of the blues. After all, how can we define the word “roots”? Does it not lead us to a too static view, as if we would look for a river source? I prefer to see in the first place that there has been a continuous historical transformation process, a creative interaction of cultures within a very particular historical context. The step from ‘lash to cash’ has been but one of the developmental stages, later followed by other equally important ones: the failure of the Reconstruction policy, the legal anchorage of the segregation doctrine, the spread of the popular media owned by the white class, the introduction of the ‘race records’, … During each of these stages we have seen how the black music changed as a survival kit for its ‘owners’, and yet remained faithful to its basic non-Western idioms. As long as the modern blues respects this vernacular speech from the bottom of society, it will surely survive.

______________________________________________________

SOURCES

______________________________________________________

– Stephen Doster: The Importation, Adaptation, and Creolization of Slave Leisure Forms in the Americas: 1600 to 1865

– Henry Edward Krebhiel, Afro-American Folksongs : A Study in Racial and National Music, 1914

– Milan Zafirovski, The destiny of modern societies: the Calvinist predestination of a new society, 2009

– D.K. Wilgus, in: Alan Dundes, Mother wit from the laughing barrel, 1990

– Martha B. Katz-Hyman, Kym S. Rice, World of a slave, 2011

– James Walvin, Black ivory: slavery in the British empire, 1992

– Paul S. Boyer,Clifford Clark,Sandra Hawley,Joseph F. Kett,Andrew Rieser, The Enduring Vision: A History of the American People, 2008

– Annemarie Bean,James Vernon Hatch,Brooks McNamara, Inside the minstrel mask: readings in nineteenth-century blackface minstrelsy, 1996

– LeRoi Jones, Blues People, Negro Music in White America, 1963

– Lawrence W. Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom, 1977

______________________________________________________

FOOTNOTES

______________________________________________________

(1) Anansi, the trickster is a spider, and is one of the most important characters of West African and Caribbean folklore. In the tales, some of the best-known in West Africa, Ananse was synonymous with skill and wisdom in speech. Ijapa is a turtle in the West-African Yoruba folk tales: he is greedy and cunning, but also a clown and practical joker, who believes that he knows the answers to all problems.