ALBUM REVIEW: ‘Playing for the Man at the Door’ Gathers Gems From Mack McCormick’s Field Recordings

After traipsing all over the countryside hanging around out-of-the-way juke joints and knocking on doors trying to run down obscure local or regional performers and record them, most field recording collectors want to share their findings with the general public.

The father-son team of John and Alan Lomax, who scoured the world recording folk music from the 1920s through the 1960s, resulting in thousands of recordings that reside in the Library of Congress, are our best-known collectors. Folk music collector Mack McCormick started his work a bit later than the Lomaxes, scooping up recordings from artists in what he dubbed “The Greater Texas area” — including Western Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, and sections of Oklahoma and Arkansas — in the 1950s and ’60s. But unlike the Lomaxes, McCormick wasn’t inclined to share. Although he racked up a considerable amount of material, he kept it mostly to himself unless he could use it for articles and a book he was writing on American roots music.

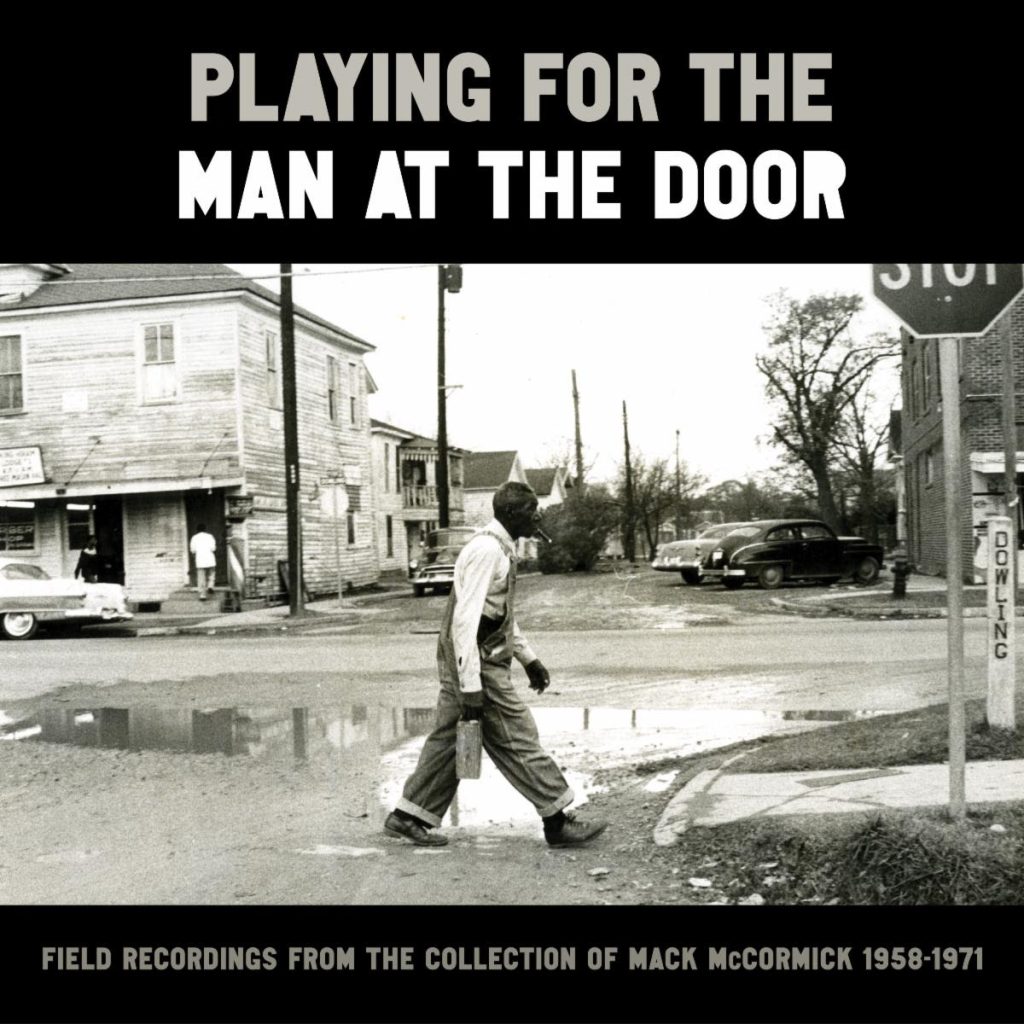

McCormick died in 2015, and samples from his collection are being released by Smithsonian Folkways as a three-CD, six-LP box set titled Playing for the Man at the Door: Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick, 1958–1971. The set, with 128 pages of liner notes, comes on the heels of the release last spring of McCormick’s unfinished book on Robert Johnson, Biography of a Phantom: A Robert Johnson Blues Odyssey, edited by John Troutman, curator of music and musical instruments at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. The museum is also displaying a selection of items from McCormack’s archives. (Read more about McCormick’s troubled life and Troutman’s work with his archives — known as “The Monster — in No Depression’s summer journal, available now.)

Unknowns are the stars of this 66-track box set, but you get a healthy sampling of the big boys as well, including 13 cuts from Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb.

“I doesn’t have my little tick tick behind me,” Hopkins is heard saying about his solo acoustic presentation on “Mojo Hand.” “But I got my own stuff now.”

He ain’t kidding, as he proceeds to demonstrate his skills as a one-man band. His fingerpicked guitar sounds like a full orchestra as he narrates the serious business of going to Louisiana and getting a powerful gris-gris bundle to hex his woman so she can’t have no other man. The song has become a set staple for countless bluesmen, and a phrase from the song found its way across the world and into the lexicon of a Jamaican singer named Robert Nesta Marley, who incorporated the lyric “cold ground was my bed last night / and rock was my pillow too” into his 1974 tune “Talking Blues” from his Natty Dread album.

Hopkins teams up with Melvin Jack Johnson slinging a bucketload of boogie-woogie licks around on “The Slop,” a talking blues suitable for a slow, drunken drag across the dance floor.

But it’s just as much fun to go rambling through the collection to the lesser-knowns and also-rans for some previously unreleased goodies. Dennis Gainus gleefully proclaims the titular phrase on “You Gonna Look Like a Monkey When You Get Old” over a brushed snare skiffle background sprinkled with rattly ragtime piano. On “Someday Baby,” Robert Shaw’s big shoulders piano sounds as clear as if it was recorded yesterday, a slow-walking blues with Shaw striding majestically up and down the keyboard.

His baby has given him some poisonous love bites, R.C. Forest laments on his acoustic rendition of “Black Widow Spider Blues,” complaining that “she bit me and gone / wish somebody would go ahead and call the doctor.”

With just a piano and handclaps as a backdrop, The Spiritual Light Gospel Group takes care of church business with some bouncy praiseology and celestial shouting on “My Work Will Be Done,” their sound obviously an inspiration for today’s powerhouse gospel group The Legendary Ingramettes, who have been burning up folks festival stages with their incendiary gospel performances.

Edward “Buster” Pickens’ “The Ma Grinder” is a disjointed ramble that probably had patrons hopping up and down spilling their drinks trying to keep time with his eccentric piano antics. CeDell Davis’ Hill Country-flavored boogie-woogie skills are displayed on “It’s Alright,” highlighted by his pocket-knife slide technique.

Playing for the Man at the Door has plenty of quirks and hidden treasures that pop out every time you drag it out for a listen, a good-time prescription for all ages.

The CD and digital versions of Playing for the Man at the Door: Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick, 1958–1971 are out Aug. 4 on Smithsonian Folkways. The vinyl set is expected Sept. 8.