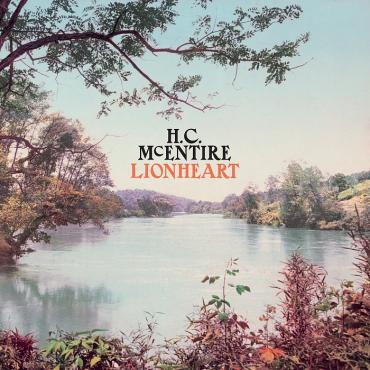

Big Emotions, But No Mud on the Boots in H.C. McEntire’s Solo Debut

I know this is completely irrelevant and probably irreverent as well, but the first thing I did when I pressed play on H.C. (Heather) McEntire’s Lionheart was sing “I fell in the pit / you fell in the pit” along to the opening cut.

I wasn’t trying to be a jerk – I just couldn’t help it. “A Lamb, A Dove” starts out so measured and sincere. A tender piano chord starts each languid bar, and McEntire sings, “You’re in my blood / you’re in my head / you’re in my eyes / you’re in my bed.” Yet it took several listens to get there. The first few times I hit play, I’m sorry to say, I found myself compelled to sing Chris Pratt’s absurdly sincere song from Parks and Recreation. The chord progression and the phrasing are simply too similar – plus, it’s this kind of hyper-sincere music he was lampooning in the first place.

Once I got past this dumbass inclination of mine, I was able to parse what McEntire is doing on “A Lamb, A Dove.” It’s a beautiful tune, really, and it sets the stage for the whole album. McEntire sings directly to a lover, infusing an intimate bedroom conversation with Christian imagery. “I have found heaven in a woman’s touch,” McEntire sings. “Come to me now / I’ll make you blush.” As Mount Moriah’s songwriter and vocalist, McEntire has spent years exploring this perspective to deserved acclaim. She’s a queer woman who was raised by Southern Baptists, and she gives voice to the stress, struggles, and victories of such a life.

McEntire’s consistently gone beyond songwriting, too, in activism and in instilling confidence in young women and gender nonconforming people, as she did when she was on staff with Durham, North Carolina’s Girls Rock NC.

Knowing all the valuable work she’s done, I wish, wish, wish I could get into her solo debut, Lionheart. But, my god, it’s too dang serious. Across nine tracks and about 35 minutes, McEntire presents exceptionally pretty, genteel indie-country – indeed, aside from some changes in instrumentation, it plays like it could be the fourth Mount Moriah album. Across Lionheart’s mid-tempo laments and blues-rock bruisers, McEntire lays all her emotions on the table with uncompromising sincerity.

One reason this album may fail to hook me is that too much of the action takes place in McEntire’s head. The imagery is all there – McEntire’s love of geographical detail, for instance – but the songwriter’s introspection most often takes the wheel. “Lay me down easy / in the valley or the pines / the Green River Gorge / above the South Carolina line,” McEntire sings in “When You Come For Me.” It’s a heartbroken country-gospel hymn, complete with pedal steel and measured, sympathetic piano, yet the mountains, the scenery, even the roadside junkyards sound conceptual, like elements seen out a car window rather than explored in person.

Indeed, Southern Gothic elements populate Lionheart, and most often as metaphorical devices. And this is one place where McEntire loses me – I find myself wanting the action to leave her head and exist in the gorgeous landscape she’s describing. I want her to get some mud on her boots! On “Red Silo,” she does. “Back when this whole town smelled like tobacco / back when we thought this would last forever,” McEntire sings, evidently simultaneously referring to the exponential gentrification of her city, Durham, and to a lost, missed love.

Indeed, McEntire’s a very intimate songwriter, which is her strength and her weakness; the songs written directly to another person or within a very specific scenario are the strongest. Take “Dress in the Dark,” for instance. Lionheart‘s closing track opens up with the sparse, tense atmosphere of a Morricone showdown theme, and McEntire describes a relationship in similar terms. It’s a bold song, with McEntire outlining the lovers’ differences (“I’m everything you’re not”) without backing down or even blinking. “I can only feel your heart,” she declares in the chorus, “through your dress in the dark.”

McEntire’s heart-on-the-sleeve sincerity can be excessive and, I’m sorry to say, several songs are overly conceptual and uninteresting. On the songs that do click, however, you’re able to see the world through her eyes. And it’s in those moments that this uneven album is well worth the listen.