These thoughts have been turning over in my head for the last month as I’ve been listening slowly through all 36 discs of ‘The 1966 Live Recordings,’ the new Bob Dylan box set. By this time, everyone knows at least a little bit of the story of how the young Bob Dylan, darling of the progressive left and the burgeoning folk revivalist scene scandalized acoustic orthodoxy by playing music on electric instruments at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965. How he was treated like an errant schoolboy, once so full of promise, that had succumbed to rock and roll capitalism. They came at him like turtle necked Pol Pots, college educated cultural revolutionists promising re-education for the wayward bard. The small groups of disgruntled purists who gathered in cohorts to wage pitched battles with Dylan and his band during the electric portion of his show were not insincere. They just had no sense of the change in the air and that history was about to leave them behind.

Fifty years on, it’s hard, really hard to understand what all of the fuss was about. Even in 1966 there was lots of loud, electric rock music on the radio and for sale at record stores. We were less than a year away from Jimi Hendrix and Purple Haze, Cream and The Grateful Dead so it’s not as if the sound Dylan and his bands were cooking up came from a galaxy far far away. Rather, it is more of an indication of the elitism and inflexibility of the new folk movement, which had initially embraced him to drop him when he no longer played by their rules. It’s difficult to imagine a creativity as wide-ranging as Dylan’s finding at home in a scene that required artists to sing about certain subjects in a prescribed way, played on specific instruments with almost identical chord progressions. By 1966, Dylan clearly felt hemmed in by the structures he had created as well as the lock step nature of a segment of his audience who had set their ideas about who he was in stone.

That Bob Dylan didn’t consider himself to be a political agitator or a protest singer or even ‘just’ a folk singer was lost on many of his early admirers. By the mid-sixties Dylan had developed a greater sense of what was possible to express in a song and he didn’t want to be limited either by his previous style of music or even his old songs. When he went out on the road in 1966, he didn’t pander to his audience’s expectations and play ‘Blowing in the Wind’ or ‘The Times they are a Changing’ or any songs in a similar vein. Even though those songs were only a few years old, they felt as if they belonged to another lifetime and to sing them would have been insincere. But, for his audience, this was clearly an outrageous approach to playing a concert. Perhaps, the fact that Dylan stuck to new songs that he thought were just as good as anything else he’d written was just as important a factor in the audience’s reaction to the tour as the introduction of electric instruments. It wasn’t so much that Dylan’s new music was loud as that he refused to fall into line and give his audiences what they thought they wanted.

Fifty years later, it could be argued that an enduring artistic vision has triumphed over the temporary desires of the fickle marketplace. As much as I have no idea of what Dylan’s aesthetic appraisal of the 1966 tour is half a century later, it must be gratifying for him to see the value of what he fearlessly offered confirmed and celebrated now that the dust has settled and lots of water has passed under the bridge. As brave and as seemingly implacable as Dylan’s persona often appears to be, it can’t have been an easy thing to go out on such a high wire night after night with no net in sight.

None of that mattered as soon as I started listening. I forgot all of the backstories and heard nothing more than great music, pure and simple. Listening through the concert recordings, I did not hear a man who was choosing to confront his audience and give them what was ‘good for them.’ I did not hear an artist who was consciously trying to change rock and roll. What I heard was a singer who knew that he had written some very good, challenging new material, working his hardest to serve that material so that it came off as well and ‘completely’ as possible.

In 1966, Bob Dylan was in the eye of a personal creative hurricane, and was experiencing breakthroughs more quickly than he could absorb them. Yet, nothing sounds rushed, offhand or insufficiently considered in any of the performances on the tour. It doesn’t matter which of the shows you choose to listen to. The performance of each song on every show communicates a work ethic that has never been surpassed in popular music. As anarchic as the performances may have seemed at the time, very little was left to chance. There’s not a lot of variation in any of the set lists. Dylan and his band were well-rehearsed and by the time they reached Europe, the songs were focused, cutting and dangerous. Very few tours, this side of Bob Marley’s ‘Babylon By Bus’ global crusade in 1978 have communicated such a complete commitment to an artistic and aesthetic vision.

Dylan’s voice has long been a subject of parody, but I can’t imagine that anyone who listens carefully to his singing here would fail to recognize the attention and commitment he was making to develop a unique style of phrasing and annunciation. To push such an unconventional way of singing to ‘the limit’ as he was by 1966 communicates a perseverance, integrity and belief in oneself that is too rarely evidenced in popular music.

One of the obstacles, of course, for those of us who are hearing these concert recordings for the first time in 2016 is that it’s impossible to experience the music in the same way as the original audiences did. In 1966, concert PA systems were downright primitive and the recording equipment used to capture the shows didn’t do much to help the situation So, a certain amount of imagination and overcoming the boom and hiss of the tapes is necessary, but that’s not the fundamental challenge. Rather, it’s that in the ensuing years, songs such as ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ and ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ have become classics, rock and roll standards and they’ve taken on so much weight over time that it’s impossible to hear them with fresh ears. What is staggering to consider is that all of these songs were brand new then and at the time were likely considered, even by Dylan himself, to be simply the product of a few months work with no conception (or intention) of the impact they would create.

It’s difficult to think of any other popular artist who ever set out on tour with as challenging a set of songs as Bob Dylan did in 1966. Then, as in now, the primary goals of touring were to entertain, and from a business perspective to expose audiences to a performer’s music. Since then, artists from Neil Young to Joni Mitchell to Prince have toured exclusively on new material, but it’s never been a very popular proposition for most music fans. As accomplished as Dylan’s earlier music was – one could hardly call ‘Hollis Brown’ or ‘God On Our Side’ easy listening fare – there was little in it to prepare audiences for the psychedelic, beat poetry inspired full contact hallucinatory assault on the senses that his new songs forced them to contend with.

So much has been written about how Dylan’s electric music upset his audiences, that it’s easy to forget just how daring and demanding the acoustic portion of each show was. For, other than in the obvious differences between the sound of the full band and solo music, surprisingly little has been written about the acoustic sets, which is a shame because in many ways, they offer the greatest surprises. Listening through the acoustic sets of each show in consecutive order, and it’s possible to come to the conclusion that it wasn’t simply the electric sound that some members of the audience objected to, rather it was the uncompromisingly intense demands imposed by of ALL of the songs that set them off. Was Dylan assaulting his audience, giving them no room to breathe, or was he simply giving them the benefit of the doubt by assuming they’d be able to follow along? Looking back, he was asking a lot of his audiences. Even though they’re musically simple, the acoustic songs are very complex. They are poems for the end times and paintings set to music that offer no breaks and no point of recovery. Such a full on aesthetic assault, surrealistic wolves in acoustic sheep’s clothing, must have been disorienting if not exhausting for both the artist and the audience.

What must it have been like to walk out on stage to present these songs like again and again? Over the years, Bob Dylan has learned to harness his energy while still maintaining his integrity as an artist, but in 1966 he offered himself up so completely that it almost killed him. Was it worth it? Listen to any of the performances of ‘Visions Of Johanna’, ‘Fourth Time Around’ or ‘She Belongs To Me’ and you can hear where all the energy and passion went. It vibrates inside of every phrase and melody. Sure, there are a few nights where the harmonica solos are almost unbearably long, designed as a sonic counterpoint to the abrasive feeling in the concert hall. On a few occasions, Dylan’s phrasing becomes weirder, more drawn out and elliptical than usual, but for the most part every song and every performance has a focus that is frightening.

But, Bob Dylan was clearly not interested in being a provocateur. Listening to the concerts, I came away with the impression that Dylan was genuinely surprised by the reaction of some of his audience. That his fans who had followed him and supported his earlier, very committed music and the visions it communicated were not necessarily open to hearing new songs that were more about art and language than social justice was lost on him. In the end, their reactions weren’t just a response to the abrasiveness of the electric sound; his audiences were experiencing a deeper sense of discomfort than anyone realized. In Dylan’s earlier songs, he invited his audiences into his circle as confidantes, who agreed that Hattie Carol didn’t get any justice, that the answer was blowing in the wind and that the times indeed were a changing. His new songs engaged the mind through rhyme, image and association, and the language of dreams. The intensity of his focused phrasing and his rapid fire delivery gave his audience nowhere to stand and no easily identifiable heroes or villains. To take in ‘Visions of Johanna’, ‘Desolation Row’ and ‘She Belongs To Me’ back to back must have sent them reeling even before Dylan added the electric rhythms that demanded a physical response to haul the audiences, ass and body into the fray of the show’s second half. The music’s undercurrent of impatience and agitated sexuality was Elvis, Old Weird America writ large, but the audience didn’t know how to respond. Really, how do you shimmy and shake your hips to ‘Ballad Of A Thin Man?’

The closest Dylan ever came to approaching the same level of chaos as he achieved on the 66 tour was when he once again abandoned his old songs in favour of his new Christian gospel music. Then, as years before, he confronted his audiences with new language and imagery. That, the next time around, he presented a landscape marked by sin, struggle and redemption rather than jewels, binoculars and ghosts of electricity didn’t make any difference. The effect on his audiences was very familiar, but in the eighties as in the mid-sixties, he changed when he was ready. And, he has changed often. The motorcycle crash in the summer of 1966 opened another doorway into a period of bucolic family life that ushered in another new phase in Dylan’s music. If being sidelined and taking a break from recording gave people a chance to catch up and absorb ‘Highway 61 Revisited’ and ‘Blonde On Blonde,’ by the time anyone heard from Dylan gain, he was onto something else. Desolation Row had receded into the distance and he reinvented his approach to music again with the simple direct sound and parables of ‘John Wesley Harding.’ That brief moment of time and all of the chaos, boos, drugs, poor health and the demands of walking the razor wire of thin white mercury would never come again. That kind of sincerity, such naked vulnerability is something a person could only survive once.

By the time Bob Dylan toured again with The Band in 1974, almost everything had changed. The culture had caught up, the artists were icons, the songs were enshrined classics and the concert PA sound systems were much better. And, if audiences at that time missed the by the seat of the pants hysteria of complained about the lack of anarchy of the 1974 tour, consider that if things had continued on in the direction they were headed, things could have gone dreadfully wrong. For my part, I am happy to have been spared that train wreck in exchange for all of the great music from ‘Blood On The Tracks’ to ‘Love and Theft’ to ‘Modern Times’ that we may not otherwise have had the chance to hear if things had been allowed to carry on in the direction they were heading.

Still, in terms of sheer excitement and straight out on a limb artistry there are very few expressions of creativity anywhere – in any form – that equal the music Bob Dylan unleashed on unprepared audiences in the winter and spring of 1966. If you weren’t there, ‘Bob Dylan – The 1966 Live Recordings’, the handsomely presented and meticulously prepared record of that tour is as close as any of us are going to get. As daunting as the prospect of listening to 36 discs from 22 very similar concerts may seem, it’s more than worth all of the time it takes to absorb and appreciate the music. It was truly a tour like no other.

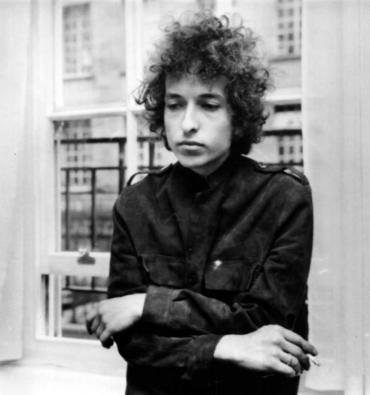

Bob Dylan.

He’s an artist. Look Back.

This posting originally appeared at www.restlessandreal.blogspot.com