Boxing Little Richard

He’s the originator, the agitator, the disturber, the upsetter, the architect and the anti-christ of rock and roll. There’s never been anybody or anything like him, before or since. Little Richard started something that nobody knew they needed till he created it, then found they couldn’t do without it. Others tried to usurp his raucous magnificence, but Little Richard Penniman did it faster, harder and raunchier than anybody else.

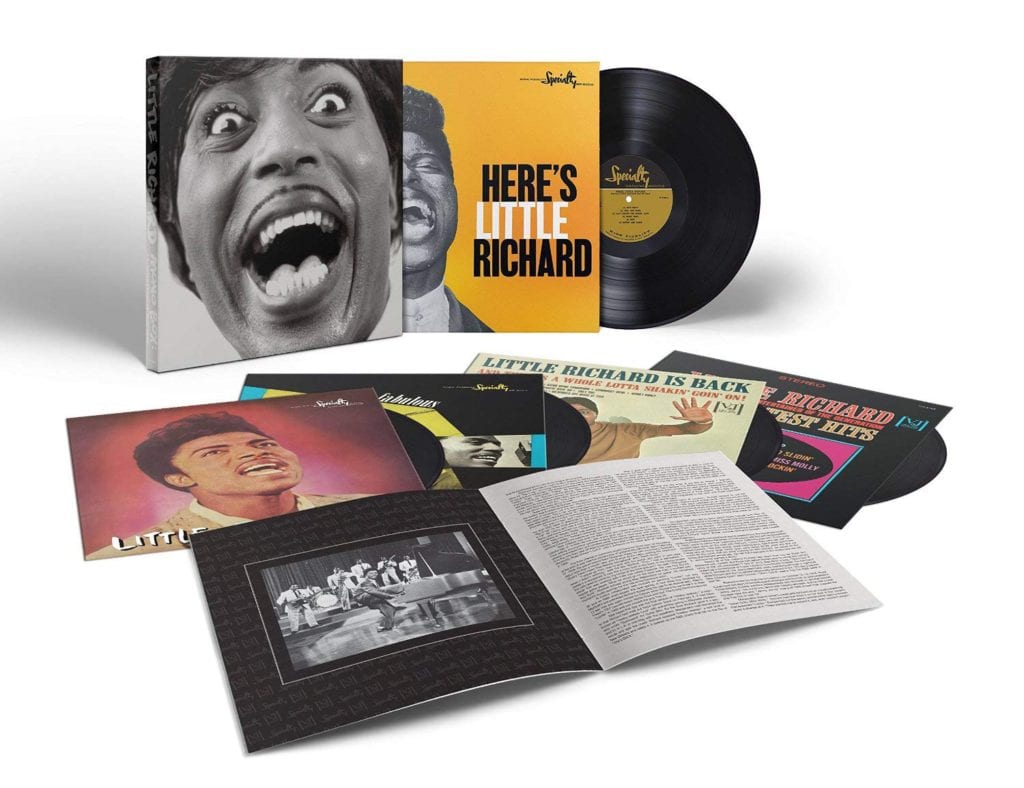

Concord Music Group has re-released Richard’s catalog from 1955-1964, three on Specialty, his first label, and two more released later for Vee-Jay. The five album box set is on vinyl with the original sleeves recreated faithfully, with original liner notes intact on the back.

It’s as recorded, in mono, but it sounds great. For those who didn’t grow up up with vinyl, even in mono there’s a depth of sound you just don’t get anymore. For those of us who had it as the soundtrack to our lives, it’s a welcome shock to put this stuff on again and have it leap out of the speakers, rattling your windows and vibrating the floor with its power and glory.

The packaging is just as startling as the music. On the box set sleeve, Richard’s larger than life visage leaps out at you in all his full blown, bug-eyed glory on the front and back cover. Inside, the imagery is just as jarring. The cover of his eponymous `58 release has Richard looking so churchy that you’d almost believe he’s about to fall on his knees and ask forgiveness for all the wop-bop-a-loo-bop he’s committed over the years. Not yet- that’s still a few years down the road. The material included here would have shaken any house of worship to its very foundation with Richard cutting loose on “Lucille,” “Keep a Knockin’”and “Good Golly Miss Molly.”

But on the ’57 Specialty debut entitled simply Here’s Little Richard, what you see is what you get. Richard’s in full cry on the front cover, eyes shut, brow furrowed, rivulets of sweat running down his face. If that isn’t enough, on the back Richard is painted head to toe in devil red, squatting like man howling in gastric distress on the bottom left, and up top, caught in mid-roar, glaring at the mic like he’s either gonna swat it or eat it if it doesn’t deliver his message properly. But the real message is on the inside, breaking loose with “Tutti Frutti,” “True Fine Mama,” “Ready Teddy,” “Slippin and Slidin’,” “Long Tall Sally,” “Rip It Up,” “Can’t Believe You Wanna Leave,” and “Jenny, Jenny,”- the core of a set list Richard would use for the rest of his career ensuring that whoever was on the bill with him would not want to follow this.

Little Richard was considered dangerous to young morals with his flamboyant appearance (wearing eye liner and pancake makeup in the ’50s) and raunchy, rip it up style of music that had teens gyrating in ways that had elders of the era proclaiming that the younger generation was surely going to hell.

Some tried to dilute his music, homogenizing it for what they thought would be a broader audience. But kids weren’t fooled. Clean cut Pat Boone’s recording of “Tutti Frutti” was ludicrous, and no cool teen wanted anything to do with Mr Clean’s lame rendering of Richard’s raucous original. As Richard said in an interview in the ’87 Chuck Berry documentary Hail, Hail Rock and Roll, “they played Pat Boone covering my songs in the living room, but they put me on in the bedroom.”

Bill Dahl has compiled an exhaustive account of the recordings in an accompanying booklet big enough to read without squinting. For those born too late, back in the day, albums came in packages with print you could read from across the room and part of the thrill of getting a new record was reading new gossip about your favorite entertainer as the disc spun, filling the room with the stuff your parents didn’t want you to hear.

Richard didn’t read music, but knew what he wanted. For the intro to ’57’ s “Keep A Knockin‘,” Richard tried every instrument in the band and his own vocal, but wasn’t satisfied. Finally drummer Charles Connor, who had worked with Professor Longhair and Smiley Lewis as well as Shirley and Lee suggested he try it, making rock and roll history with the first 4 bar drum intro, and netting himself a thousand dollar award from Richard.

On the road and in the studio, Richard always had a band that could blow the doors off anything he came up with. Jazz drummer icon Earl Palmer played on Richard’s ’55 debut, Here’s Little Richard, recorded at Cosimo Matassa’s New Orleans studio. He had two of the best blasters on the planet, Lee Allen and Red Tyler blowing buzzsaw saxes on that date as well. “Tutti Frutti” was a smutty ode to booty boppin’ that Richard composed while washing dishes at the Greyhound bus station in Macon before he was discovered. Local songwriter Dorothy LaBostire sanitized the song, but Richard’s frenetic delivery pounding piano and top of the register WOOOO! made sure it still had quite a punch.

Listening to this stuff today still brings a smile to your face. It‘s fun music, everything that rock and roll’s spozed to be-loud rude, and dangerous. “Tutti -Frutti” still pops. I dare you to stand still when “Long Tall Sally” comes on. Even when he tackled filler like “By the Light of the Silvery Moon,” it crackled and snapped when prodded with his raspy vocal lash. But he could handle the slower, soulful, bluesier stuff as well, sounding like a slightly rougher version of Ray Charles on “I’m Just A Lonely Guy,” from ’59’s The Fabulous Little Richard. Jerry Lee Lewis‘ signature tune “Whole Lotta Shakin’” isn’t safe from Richard’s makeover, Richard trying to exceed Jerry Lee’s land speed record for rapid fire lyric spittin’ and frantic piano pounding. Even the band’s name, the Upsetters, was a warning about what to expect when the show hit town. “We were supposed to go and upset every town we played in,” Connor says. Richard told the band “If another band jumps off the stage, I want you to jump off the roof of the house.” Richard’s shows were famous for starting riots when he started ripping off his clothes and tossing them in the audience.

All that wildness comes through on vinyl, his raucous essence preserved in wax as pristine sounding as it was when recorded over half a century ago. The music hasn’t aged. You could put this stuff out today or play it live and still get everybody upset. Thanks, Richard, for a lifetime devoted to showing us how to rip it up.