Bruce Springsteen at the Starting Gate Plus More New CDs

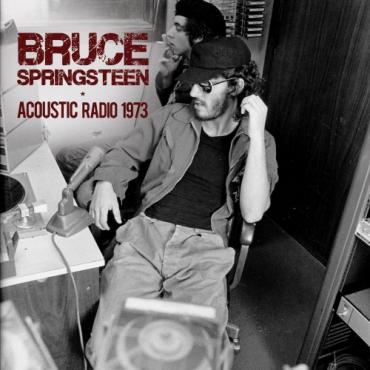

For Bruce Springsteen fans, hearing the two-disc Acoustic Radio Broadcast Collection will be a bit like Beatle lovers listening in on the Fab Four at the Cavern Club in Liverpool.

The recently issued set includes his very first radio appearance, on Boston’s WBCN on Jan. 9, 1973, which occurred within a week of his debut album’s release (though he performs only one number from it), plus broadcasts from May 31, 1973 (WGOE, Richmond, Virginia); March 9, 1974 (KLOL, Houston), and April 9, 1974 (WBCN again).

A little over a year after that last date, in August 1975, Springsteen would play a series of important dates at New York’s Bottom Line, release Born to Run, and ride a rocket to fame. But when these broadcasts occurred, he was struggling and little known. I talked with him in January 1974 for one of his first interviews for a national publication, and he spent a big chunk of the conversation telling me about his financial problems and how he could barely afford to pay his band members. (At the time, he was making a reported $75 a week.) At the end of our conversation, after I told him I loved his new second album but hadn’t heard his first, he offered to send me his copy because, he said, he couldn’t afford a record player to play it on.

Acoustic Radio Broadcast Collectionis by no means the only surviving example of how Springsteen’s music sounded during this period. There’s an independently released collection called Before the Fame that captures even older performances—from 1972, before he signed with Columbia—and there’s vintage material on the 1998 four-CD Tracks box set. There are also lots of bootlegs. Even fans who have some of these recordings, though, will likely be fascinated by Acoustic Radio Broadcast Collection.

On these recordings, it is mostly the spoken parts that suggest we’re listening to a relative novice: talking with DJs, Springsteen sounds much less articulate than he does in later interviews and offers a lot of nervous laughter. On the January 1973 WBCN broadcast, he says, “This is my very first time on the radio, and I want to say hello to my mother, who lives in California. Hi, Mom!” Back at that radio station in 1974, he thanks it for airing his music, noting that when the band first came to Boston, they played to audiences of 10 or 20 but that now, “there must be about 50 people in the place.”

Though Springsteen had yet to achieve major success when these broadcasts were recorded, however, his music was already inventive and often fully realized—which should perhaps come as no surprise, since he had by this time been a working musician for years. The performances, which most resemble those on his Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. debut LP, include several numbers that surfaced on that record: “Does This Bus Stop at 82nd Street?” (three versions), “Growin’ Up” (two versions) and “Mary Queen of Arkansas.” Compositions that turned up on his second album, The Wild, the Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle, include “Wild Billy’s Circus Story” (four versions, two called simply “Circus Song”); “4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)”; a joyous “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight); and “New York City Serenade” (here called “New York City Song”). These last two differ the most from the versions Springsteen later released.

Other originals on these CDs include “Bishop Dance,” which you can also find on Tracks; “The Fever,” which became a concert staple for both Bruce and Southside Johnny; and the rather obscure “Song to Orphans” and “You Mean So Much to Me.” Also here are two takes of “Something You Got,” the Chris Kenner oldie (one melded with Martha & the Vandellas’ “Heat Wave”), and a few surprising covers: “Sentimental Journey,” the pop standard, and Duke Ellington’s “Satin Doll” (four versions, no less), featuring Garry Tallent on tuba and Danny Federici on organ.

In none of these performances do I hear any hint of the sound that would emerge on Born to Run and later albums; but you can already sense in these recordings Springsteen’s love of language, musical adventurousness, and originality. Certainly, there’s more than enough here to explain why John Hammond wasted no time in signing him to Columbia.

BRIEFLY NOTED

Tony Joe White, Bad Mouthin’. Tony Joe White is known primarily as the writer of such hits as Elvis Presley’s “Polk Salad Annie” and Brook Benton’s “A Rainy Night in Georgia.” Now 75, he steps front and center on this album, which shows how much you can accomplish with just a voice, a guitar, and a sterling batch of material. Though a drummer backs White on a couple of tracks, the bulk of Bad Mouthin’ finds him performing solo with his 1965 Stratocaster. He applies his variously anguished and menacing vocals to a half-dozen originals, including two of his earliest compositions, as well as to such blues chestnuts as Big Joe Williams’s “Baby Please Don’t Go,” Luther Dixon’s “Big Boss Man,” and “Charlie Patton’s “Down the Dirt Road Blues.” Also here: “Boom Boom” from John Lee Hooker, an obvious influence on White’s vocals; and a slow-paced “Heartbreak Hotel” that conveys a whole lot more misery than the famous Presley recording.

Joe Ely, Full Circle: The Lubbock Tapes. Veteran country rocker Joe Ely has been delivering some of his best work in recent years, but his early stuff—while not quite as distinctive—has its merits as well. This CD offers 15 examples culled from two sets of demos. The first batch, from 1974, led to Ely’s debut on MCA Records three years later; the second bunch, from 1978, preceded his third LP for the label, which—according to liner notes here by his steel guitar player Lloyd Maines—spent 20 years trying to decide “if Joe was too rock for country or too country for rock.” In fact, he does have a foot in each camp, but the blend generally serves him well, except perhaps in the view of some pigeonholing record company executives. Ely penned nine of the songs on this anthology; another came from Ed Vizard, a one-time Asleep at the Wheel member; and the remaining five are by Butch Hancock, who cofounded the Flatlanders in 1972 with Ely and Jimmie Dale Gilmore. A few tracks are below par but the bulk of this package showcases what is obviously a burgeoning talent.

Galen Ayers, Monument. Galen Ayers, the daughter of Soft Machine cofounder Kevin Ayers, had no intention of getting into the family business. “I tried so many things not to be a musician,” a press release quotes her as saying. “But it just keeps coming back.” I’m glad it does, because this pop/folk debut is a winner. Her unaffected soprano conveys intimacy; and in the rhythmic songs—all written by Ayers on the Greek island of Hydra, where Leonard Cohen also lived—she finds original ways to tackle familiar turf about love and loss. There are echoes of 50s and 60s pop and folk singers in these tracks—everyone from Astrid Gilberto to Shelley Fabares, as well as more recent acts like the Sundays’ Harriet Wheeler and Aimee Mann. The dreamy instrumentation fits beautifully with Ayers’s vocals and impressionistic, often sad lyrics.

________________

Jeff Burger’s website, byjeffburger.com, contains more than four decades’ worth of music reviews and commentary. His books include the recently published Dylan on Dylan: Interviews and Encounters as well as Lennon on Lennon: Conversations with John Lennon, Leonard Cohen on Leonard Cohen: Interviews and Encounters, and Springsteen on Springsteen: Interviews, Speeches, and Encounters.