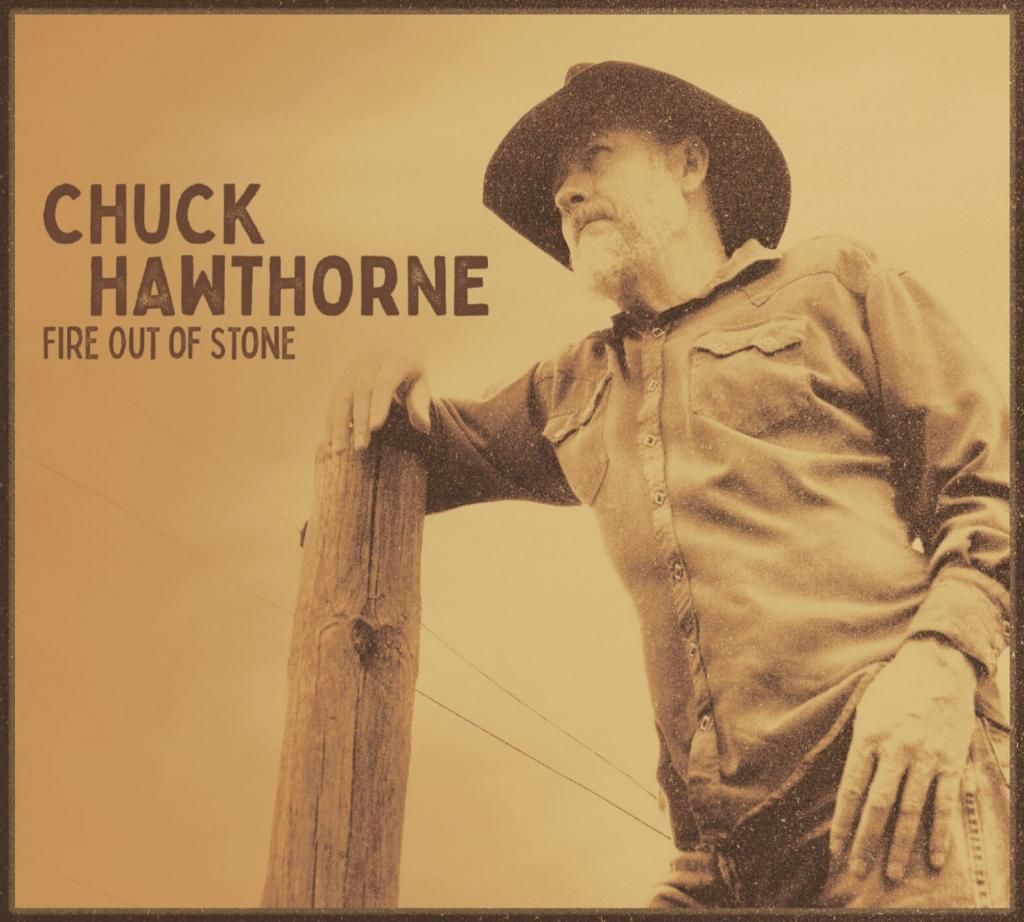

Chuck Hawthorne Balances Confidence and Vulnerability on His Second Album

Building on his debut album, 2015’s Silver Line, Chuck Hawthorne follows up with Fire Out of Stone, further honing his vocal style and exploring complex themes. Opening track “Such Is Life (C’est La Vie)” combines a folkish melody with country tones, including an old-timey viola part courtesy of Marian Brackney. Hawthorne and Libby Koch are well-matched vocally (as were Hawthorne and Eliza Gilkyson on Silver Line), offering textural harmonies, a blend of Koch’s warbly/trebly tones and Hawthorne’s solid/midrange delivery. “Amarillo Wind” opens with a sultry guitar part, Hawthorne’s vocal reminiscent of Springsteen circa Ghost of Tom Joad or the recently released Western Stars. “Her golden hair a tangled mandolin,” Hawthorne and Koch sing in unison, offering a memorably poetic image. “Arrowhead and Porcupine Claw” features Ray Bonneville’s breathy harmonica, Hawthorne opting for “talking verses” that may remind some listeners of a country-infused Jim Morrison (consider if American Prayer had been recorded in Nashville) or John Prine’s droll presentation on “The Missing Years.”

“Here lies Lonesome Jim,” Hawthorne sings on “New Lost Generation,” “paid for all our sins / he believed in everything / that he done / he believed in football scores / and far off Asian wars,” offering a “Sam Stone”-esque commentary on the hardships of the contemporary US vet (Iraq, Afghanistan), often neglected as a result of a greater cultural intrigue with World War II, the Korean War, and Vietnam. At just over three minutes in length, the track stands as one of Hawthorne’s most precisely crafted and sophisticated songs. “Broken Wire” is another stunningly oblique lyric, a nuanced portrait of the embattled survivor striving to navigate rage and addiction (PTSD), his life wrapped in “broken wire,” a metonymic reference to fuses, traps, tanks, metal shredded by explosion.

Geoff Queen’s steel guitar and dobro are notable on “Standing Alone,” a tribute to an unnamed individual and a relatively unlimned relationship. Despite Hawthorne’s lyrical minimalism, his images (“beer cans on the floorboard,” “feel like a road sign / shot full of holes”) coalesce into a haunting snapshot, a man dead in a collision (“shattered on that stone”), another man grieving his demise. The album closes with the Richard Dobson-penned “I Will Fight No More Forever,” a tribute to the Nez Perce chieftain Chief Joseph. “I will say goodbye to anger / in all of my endeavors / I will leave these tears behind / fight no more forever,” Hawthorne sings, ending his album on a seemingly triumphant and possibly appropriative note, given that Chief Joseph — whose words were, I think, spoken resignedly rather than in the spirit of resilience — died in 1904 from, according to his doctor, “a broken heart.”

While Hawthorne, who served in the military, is at his most articulate when addressing the theme of the “wounded warrior,” as he does directly or implicitly on the majority of Fire Out of Stone, his vision is more expansive, suggesting that each generation, in its own way, is ill-equipped to confront the unique problems it faces. Then there are the more universal and perennial concerns: love, intimacy, justice. Also, the constancy of change and the open-mindedness, flexibility, and equanimity required to navigate it. Throughout Fire Out of Stone, Hawthorne explores elusive social and existential issues via accessible melodies and precise lyrical strokes, his vocal characterized by a compelling blend of unshakable confidence and vulnerability to life’s inevitable losses: the singer-songwriter’s paradoxical sensitivity expressed through a well-studied craft.