Eric Bibb Finds Hope and Humanity on the Refugee Road

Eric Bibb is back, though he was never really gone, along with a boatload of new blues. And, like John Cephas once said of him, Bibb is right on time. He has an uncanny knack for being both timely and timeless, not by following the headlines, but by keeping his eye on the ball. When the culture is often obsessed with left vs. right firebombs, and with the straw men of one-sided stacked-deck debates that treat people as bowling pins to be knocked down, Bibb stays the course. He does so by refusing to be moved from the civil rights values of his upbringing. His co-conspirators on this outing are string wizard Michael Jerome Browne, and harp master JJ Milteau.

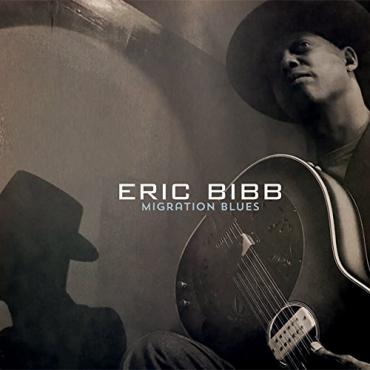

Which brings us to Migration Blues, Bibb’s new album. Fifteen tracks steeped in the traditions of the pre-war blues elders that Bibb honors, even as he brings their legacy to bear on our current times. Today’s struggle may appear different on the surface, but at its core it is still the story of people yearning to be respected and allowed to live in peace.

As he did with 2014’s Blues People, Bibb shines a light on dark moments in human history, while holding out the belief that people can choose to change for the better. Talk to the man and you see an artist who is gracious and engaging, unwilling to bow to discouragement or fear. Despite newsreels full of mankind’s lowest accomplishments, Bibb refuses to let anyone drag his spirit down. This is not a rose-colored Pollyanna view of the world. Instead it is the determined resolve of a man not afraid to stare the devil down, all the while pointing out for us a better way to live. If at times this seems out of fashion, it is all the more reason we need him.

Migration Blues is at times discomforting. It does not offer easy answers or cardboard characters we can easily dismiss. The album grew out of Bibb’s study of the Great Migration, a time in American history when millions of blacks moved from the rural south to northern cities like Chicago, seeking shelter and gainful employment. Driving this migration was poverty and starvation, and the desire to escape the domestic terrorism of the Jim Crow south. What Bibb does is place that historical moment at the center of the album and then draw connecting points to our current sociological seismic shift.

As with Blues People, Bibb uses the sequencing of the tracks to create a story arc that serves his larger purposes. “Refugee Moan” starts off the record. It is an unusual track for a number of reasons. The melody, which is sparse and starkly arranged, along with Bibb’s tentative vocal delivery, paints a portrait of uncertainty. Bibb is not singing in full voice here, but in a more restrained, locked down manner. The song is a prayer for safety and deliverance. The joyous preacher Bibb is not present, this is the sound of a desperate soul seeking protection. The song represents a prayer that has not been answered, at least not yet. The crisis is not resolved by the end of the song. The central character of the piece finds some comfort in praying not only for his own journey, but also for others who share his fate.

Next up is “Delta Getaway,” co-written with JJ Milteau. Here Bibb shows us the plight of a man on the run.

Saw a man hangin’

From a cypress tree

I seen the ones who done it

Now they’re comin’ after me

Photo by Keith Perry

“Praying’ for Shore” puts us in a boat, fleeing war. As before, the future is unclear, arrival is not guaranteed, and, if achieved, neither is the reception awaiting these refugees. Hungry and thirsty, time is running out for this band of castaways. Though they may have escaped certain death in the war, they are nearly out time, food and water. Bibb, long known for a joyful, even playful, take on the blues is travelling a trail of tears here. Leaning more on tension than release, his take on the refugee road is centered on life, and the very real chance of losing it.

Wisely choosing people over policy, Bibb reminds us that, at the center of this global crisis, there are human stories and lives at stake. The songs on Migration Blues humanize an issue that has become hijacked by rhetoric and politics, not to mention fear. While the record does not address legitimate questions about security and assimilation, it doesn’t have to. Bibb leaves those matters to others, he knows his part in the play. His role is to remind us to care for our fellow man, and, if it is necessary to err at all, to err on the side of compassion.

This is not to say the album is all gloom and doom because it isn’t. Bibb looks at a world in tribulation, and brings a steamer trunk full of hope and faith with him. That resilience underpins the whole affair and keeps it from sinking into despair. Michael Jerome Browne and JJ Milteau bring their considerable talents to the fore and provide layers of emotion to the compositions with intuitive and subtle turns. Together they buoy and challenge Bibb in his effort to tackle a complex issue in song.

While this album is birthed out of Bibb’s singular vision, it is also one of his most collaborative works to date. Three of the fifteen tracks find Bibb sharing writing credits with Browne and Milteau. There are covers of two songs by Browne, and one track, a delightfully giddy Cajun number, written by Browne and Milteau. The album also contains three excellent instrumentals. The liner notes give producer credits to all three men. Sitting in the lounge of the General Lewis Inn after his recent West Virginia gig, Bibb expressed his excitement for this project. “I’ve recorded with JJ before, but I’ve never done a whole album with Michael, and I was glad we got to do this. It was time.”

Bibb lightens the mood of the subject matter, again by sticking to the personal stories. “Diego’s Blues” tells the story of a child who is a product of migration. Born to a Mexican woman who migrated to the Delta, and a hard-working black man, Diego lives in a world of two cultures. “I was raised on tamales, collard greens and blues,” sings the young Diego. The picture is one of blending cultures through mutual assimilation.

The three instrumentals on the album are as good as it gets. “Migration Blues” would make a perfect theme song for a documentary on the Great Migration. The Cajun number, “La Vie C’est Comme un Oignon” is a nod to Milteau and Browne. Browne, an American who has lived most of his life in Canada, and Milteau, who is French, celebrate the cultural gifts that the Acadians brought to America and the world. Expelled from Nova Scotia by the British in the mid-1700s, many migrated to Louisiana, and we are made richer as a result of their travails. This exuberant tune shows the resolve of a people and way of life in the midst of forced change. It is a subject also covered in The Band’s classic, “Acadian Driftwood.” Here Browne and Milteau seem to be having a hell of a good time.

There are also covers of Dylan’s “Masters of War” and Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land.” The Dylan number addresses the origin of the current crisis, and the latter asks us if our values still hold true. If the album is lacking anything it might be a cover of Guthrie’s classic “Deportee (Plane Crash at Los Gatos).

All in all, Bibb manages to keep the subject entertaining while presenting it to the listener in a way that raises the questions. Faced with the reality of the human stories behind this great population shift, it is impossible to accept the broad strokes of the issue painted by so many in the news media. This is a result of Bibb’s quest to revere a musical tradition while striving to keep it relevant. “The trick is to be honest in the writing, while moving the blues forward so that it is relatable,” he says. With Migration Blues, Bibb has more than accomplished his mission. www.theflamestillburns.com