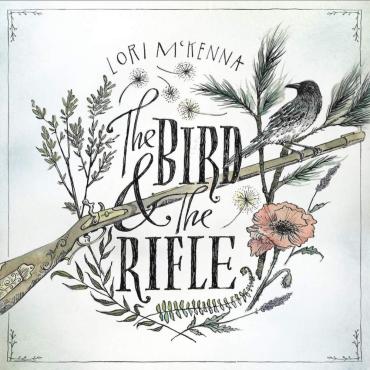

Lori McKenna has one of the most expressive voices I’ve ever heard; the fact that she can summon the words to match is a testament to the integrity of her songs. She has penned hits for Tim McGraw and Little Big Town — the latter of which, “Girl Crush,” won her a Grammy earlier this year — and has released nine albums of her own in the last sixteen years. The Bird & The Rifle is the latest and best, the crowning achievement that establishes Mrs. McKenna as a worthy successor to Lucinda Williams, a peer to Jason Isbell (with whom she shares Nashville’s most prolific producer, Dave Cobb) and — most significantly — an artist in her own right. Unsung, her lyrics read less like verse than they do prose, more Carson McCullers than folksinger. Take the stunning tercets that begins the record: “I get dressed in the dark each day / You used to think that was so sweet / By 6AM I’m in the car driving / I keep my change in the car ashtray / I haven’t smoked in years and years / But lately I’ve been craving.” Or on “Halfway Home,” the devastating resolution of the pre-chorus: “Calling the dreaming girls / Looking for a savior / He ain’t gonna save you / That’s just what you think his eyes say.” When McKenna sings these lines, the novelistic detail assumes a new dimension, her wisdom of experience made all the more real by the unsanded edges of her otherwise lilting voice. And then there’s the music itself, performed live in the studio by McKenna and a handful of session musicians, their time-tested foundation of acoustic guitar, bass, and drums adorned with just enough flourishes — piano, mellotron, electric guitar — to complement the vocals rather than swamp them. Of the innumerable artists leading the mass folk-and-country revival around the country right now, Lori McKenna has dispensed with the cliches and broken from the pack entirely.