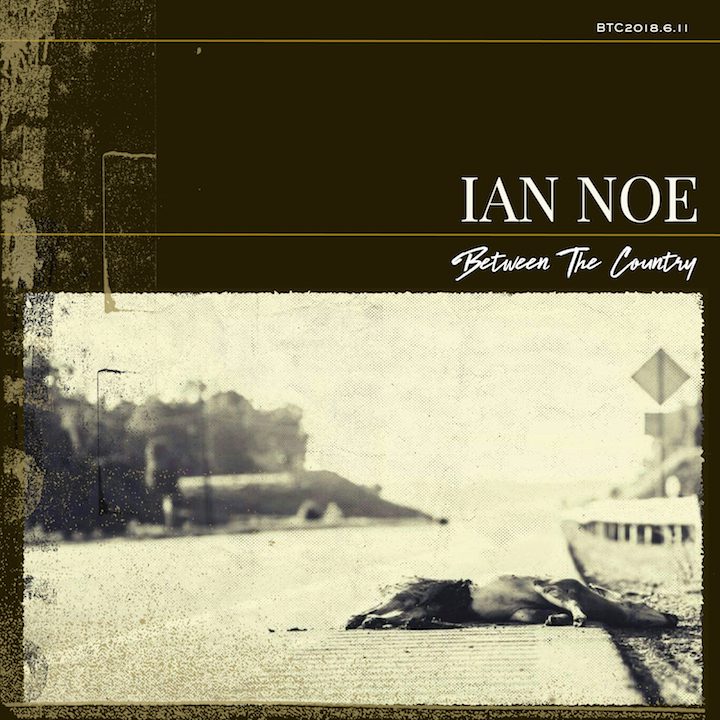

Ian Noe Brings Folklore into Stark Focus in ‘Between the Country’

Ian Noe draws a forlorn portrait of his Eastern Kentucky home in his debut album, Between the Country. The project’s songs are populated by characters who often seem drawn straight out of dark folklore: A train-hopper meets his demise on a collapsing bridge, a fugitive clutches an unmailed letter for his beloved to his breast as the law closes in on his hiding place, and a young mother washes up tied and drowned on the banks of a river.

The stories Noe tells aren’t so much sharp-edged as they are sad. With the off-handed and unassuming style of songwriters like John Prine and Bob Dylan, he takes the long view on tragedy, as if he was recounting a fable that took place a long time ago. There are, however, a few clues that (in most of the album, though not “Barbara’s Song”) we’re in the present day. The project’s first track, “Irene (Ravin’ Bomb),” sees an alcoholic woman dropping Visine into her eyes at the dinner table, for instance. Noe doesn’t shy away from tackling the addiction crisis that ravages Appalachia’s small towns in tracks like “Junk Town” and “Meth Head.” In the latter track, the narrator watches the epidemic from the outside, describing the drug’s wreckage as a zombie apocalypse. Finally, he heads outside to dig a mass grave, hoping to bury the undead as they tumble into the pit. Addicts, he reasons, are already too dead to kill — the best you can hope for is to cut your losses and start all over again.

Even darker, however, is “Junk Town,” which looks at addiction from within. In this track, the narrator’s drug of choice and his rural, impoverished hometown are inextricably linked — and he’s got about as good a chance of getting free from either. “Sometimes when I’m drinking I sit alone and wait for the sun to fade out of the sky / And I wish I was leaving to find another fate, and all the while knowing where I’ll die,” Noe sings.

Love doesn’t stand much of a chance either in this project. If relationships aren’t dogged by poverty, drugs, or alcohol, they’re typically doomed by one or both lovers’ imminent demise. As is the case in any good folk tale or murder ballad, the purest love declarations come from the lips of the dying and are passed along secondhand by a stranger who happens to be at the scene.

Despite all the sadness, Noe clearly loves the world he describes in the songs. Over and over again, his voice duets with an acoustic guitar line as meandering and delicately crafted as a spiderweb. Noe doesn’t seek to glamorize the everyday tragedy of the songs, but even in its most downtrodden moments, the album seeks out and gently cradles the real-life people and places that, in rougher hands, would be mined for parables, then tossed aside.