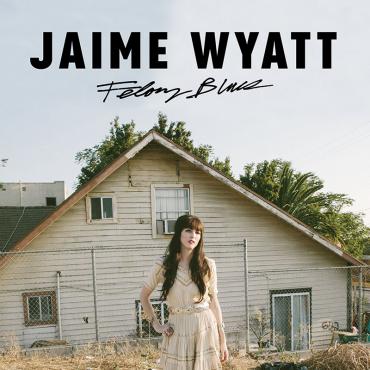

Jaime Wyatt Paints an Outlaw Country Masterpiece in Felony Blues from Forty Below Records

“Who the fuck is Jaime Wyatt?”

It’s the question asked by the stickers she hands out at every show. Yeah, ok, it’s derivative, but it lets you know right off the bat where she’s coming from. She reveres tradition but equally reveres its rebel origins. She knows those who founded establishments were those who dislodged the old ones. She respects what works and she ain’t about to let anyone tell her her business. And the stickers? They’re effective. “Who the fuck is Jaime Wyatt?” are almost invariably the first words out of the mouth of any new visitor to My Stately Manor when he or she sits down and views the logos plastered over my vinyl cabinet. We serve a classy clientele.

So, who the fuck is Jaime Wyatt?

Her label wants you to think she’s an outlaw. And it’s true, Jaime’s got the spirit of her outlaw country forebears and a stint on the wrong side of a big white wall to certify her credentials. It’s right there in the name of her most recent album, Felony Blues. That’s gotta be worth some street cred. But while her P.R. team may eat the backstory up, cred is the last thing on Jaime’s mind.

“I fought a prison sentence for 8 months in L.A. County Jail,” she says. “I took a plea deal for a felony strike 211 robbery, with 6 months rehab and 3 years felony probation.”

But when you brand someone an outlaw you risk making her into a rebel, and Jaime’s experience left her with a few… light critiques of our correctional apparati.

“The judicial system does not rehabilitate,” Wyatt continues, outlining the social and political observations that underlie her hard-luck stories. “Once you’re in it, you’re paying the government for a lifetime, for what could have been but a moment of poor decision making.

“I’m convinced it’s another way to control the public, especially the lower and middle class, since the upper class can buy their way out of most every legal problem. I robbed my dope dealer and still can hardly get a decent job nine years later. Had I been wealthy, I don’t think I would have taken such a plea deal. But the D.A. wanted to drag it out, scare the shit out of me and my family so we would keep paying for attorneys, crazy phone bills, and overpriced commissary hygienes and junk food.”

“I don’t think it taught me a lesson,” she replies when asked if she believed she gained anything from the experience. “It really has made more of a struggle in my life. The system prevents people from getting better jobs and getting ahead or even having any sort of financial security. From what I’ve seen in L.A., it kept a lot of people selling drugs and doing crime to feed their families and pay legal bills. For me, my record just kept me sleeping on couches forever, working random jobs and missing out on promotions.”

She says these days she’s embarrassed by her record and the stigma attached to it and she’s working to get it expunged, so I asked why she was nevertheless willing to focus on it so directly in her art, going so far as to dedicate an entire album to that portion of her life.

“I bitch about this on a public level,” she explains, because “other folks have similar and much worse stories of oppression at the hand of the U.S. judicial system. It would be rad to see a change someday soon. Or hey, take a chance on hiring a felon by your own intuition, since someone who has never been busted might be more likely to steal from their employer.”

So ok, she’s an outlaw, whatever. She’s a rebel. Fair enough. But who the fuck is Jaime Wyatt?

Well, ok. I’ll tell you something I know. At her core, Jaime Wyatt is a woman who lives and breathes contradiction. What is it Kris Kristofferson said about the outlaws, “partly truth and partly fiction”? Well, then, pilgrim, Jaime fits the bill.

Onstage, she’s a wild, brash, devil-may-care temptress, there to sing hard luck songs with the voice of a siren & love songs with the heart of a succubus, ready to kick your sorry Saturday-night ass straight through to next Sunday and to drink down everything the bartender can throw her way. But when the lights aren’t trained her direction, you’re more likely to find a quiet, reserved woman, introspective, maybe even a little shy, and quite possibly in need of a good hug. A flighty streak often makes it appear as if she’s not quite sure where she is or what she’s doing, even when she’s exactly where she’s supposed to be, doing exactly what she’s meant to do. She’s wistful even through giant, toothy smiles, and sparkles with hope even through forlorn eyes. She’s road weary and street smart, hurt too many times to let her personal walls crumble, and yet she carries a deep reserve of compassion within her and wants to be the trusting spirit she could have been in a perfect world. Even her felony conviction is a paradox: “strong-arm robbery” from a girl who doubles her weight when she hitches a belt buckle around her size -4 jeans, pulls on her boots, and cocks back her Stetson.

Contradictions. Yeah, boy.

She’s an unrepentantly unreformed veteran of the correctional system turned soft-touch insurgent troubadour, but that’s a tiny fraction of what defines her. She’s a SoCal-born, PacWest-raised reAngelena with the sweet-tea-flavored heart of a Southern belle. She’s never had a damn thing and maybe she never will. Forget Jesus; music is her only salvation. She plays because she needs the money—like she said, even the sweetest little ex-con this side of the San Andreas has trouble finding a straight job—but you can hear the search for personal redemption in every song, oozing out and mixing with the blood, sweat, and tears that underlie each story she tells. And on top of everything she’s a fuck up. God love her but she is. Beneath all the vintage glam and the brazen showmanship, intertwined with the immense talent that makes her writing so relatable and her performances so enthralling, and bubbling up from the deep longing she’s so desperate to fill that she’ll pour anything into the hole that might make it seem just a little bit shallower, is a woman who needs to roll the hard eight one time and just can’t get the dice on her side. Townes, Blaze, Billy Joe, Lucinda, Nikki, Jaime: they all belong on some list together.

So what kind of album does a woman like that produce when she’s at the absolute top of her game? Felony Blues, plain and simple.

Two pickup notes and the screaming guitar of “Wishing Well” open the album with the strutting attitude that marks Wyatt’s style. The Orwellian down-and-out in Southern California story that unfolds on the back beat is ripped right from Jaime’s time on the razor’s edge:

I wanna wake up somewhere where you don’t have to lose.

Bought my ticket for the rainbow and it just hasn’t come through.

Say there, City of Angels, won’t you just send me one or two?

Always try to be a good girl but I can’t really say that that’s true.

And I don’t wanna go down just like that,

So damn hard I just can’t get back.

Might be living in a Pontiac, but I ain’t cryin’.

And I’m wishin’ on a wishin’ well.

I can hear the mission bells.

The sense of longing for salvation that comes through when she holds the coda on that last line is absolutely sublime. As on the rest of the album, Wyatt’s vocal performance is spectacular, imbued with a method actor’s style and inflected with every drop of the torrential emotion she pours into her songwriting.

The more joyful duet “Your Loving Saves Me” features fellow Angelino country singer Sam Outlaw along with spritely drums and brightly rising slide guitar. Wyatt likes to say it’s “a song about Jesus” when she introduces it, but that’s only tangentially true:

Here we go around again,

Closer than we’ve ever been.

Will you lead me through the night?

I can almost see the light.

To see you two-step gliding across the floor,

Chasin’ that high hat door to door.

Maybe a little jazz or rock ‘n’ roll

To feed that Yankee heart and Southern soul

There ain’t no borders; there ain’t no boundaries.

Good, good people all around me.

Hard as concrete; soft as gravy.

Jesus is cool, but your lovin’ saves me.

That line about the diverging heart and soul strike me as emblematic of her contradictory nature, but it was to whose love the author referred in which I was most interested. Jaime was uncharacteristically cagey. Three thousand miles away, I pictured her blushing just slightly and looking away before she answered.

“All I can say is that life is really hard and painful,” she told me. “This is coming from an overly sensitive recovering drug addict, but so many people struggle in this life. But I feel like my life has been saved by friends, lovers, drugs (yes I mean that), and/or a higher power (god, Jesus, universe, whatever) on many occasions. Even once at an ER in North Ridge, California.

“Kindness and compassion change lives forever. It’s been my experience that that loving kindness can keep changing someone’s path and prevent them from ruining other lives as a result.

“So it’s either about brotherly love, a good lay or maybe just a casual smile that changed mine. I can’t recall.”

Well, that’s good enough for me.

Some of the most heartfelt songwriting on the album is found on “From Outer Space.” It’s a second bite at the apple for Jaime on this one, which was also the title track of her last album. But pairing Jaime’s mournful voice with gorgeous, seemingly boundless pedal steel and weeping violin really brings out the sense of alienation around which this piece revolves. The conceit of the astronaut is meant to stand in for Wyatt’s life as a touring musician and her feelings of isolation on the road. But for Jaime, the alienation goes deeper:

Honey, I’m an astronaut.

I can’t give you what you want.

But I, I’ll try, I’ll try to be there when you call.

Honey, it’s a long way home from outer space

And I can never predict the radio wave

Floatin’ through the atmosphere.

(I know it’s strange.)

And I can never forget where I’ve been.

Baby, it’s a long way home from space.

It’s a long way home from outer space.

Honey, it’s a long way home from outer space.

“I’m sure my feelings of being an outcast in this world stemmed from long before drugs and incarceration,” she tells me. “I think I was born with depression and a deep sensitivity to humanity, but I also come from a family rich in mental illness and addiction so that could be part of it. It also doesn’t help that my life’s calling is one of isolation and extreme criticism. Basically I hate not being accepted but will put all my flaws out into the open, in hopes that someone will identify so I won’t feel so alone. Inevitably I will be judged more than I will be loved, but I have to remind myself that love and understanding is exponentially stronger.”

And now that she’s totally torn your heart out and crushed it under her boot heel, “Wasco” adds a form of uptempo levity. It’s your classic girl-loves-boy, boy-loves-girl, boy-and-girl-are-both-behind-bars Shakespearean-style star-crossing story. And it’s taken straight from her time in jail. In fact, it turned out to be some of the best entertainment of her stay.

“My cellmate exchanged booking numbers with a dude at court and they began a love affair—via letters between two correctional facilities—and were planning a wedding, even though they hardly knew each other,” she says, delivering the TV Guide synopsis. “Quite courageous to dream such a dream I think.”

It’s a romance born to be romanticized, and Wyatt delivers with clever, finely drawn characters and the defiant declaration “Ain’t nobody gonna tell me who to love!”

Gentle waves of pedal steel signal the opening of “Giving Back the Best of Me,” a dirge-like dream of temporal and romantic redemption on the road:

‘Cause you are the sun setting to the west of me.

And you are the moon turning out the light so I can dream.

Maybe I could be your only rider.

Would you have me? I surrender.

Never gonna need another hour.

‘Cause I got you and you’ll know it.

Mmmmmm, I’m givin’ back the best of me.

It’s Jaime at her emotive best, the tremble in her voice pulling the listener right into the passenger seat with her.

The autobiography of a “pawn shop girl,” “Stone Hotel” is the epic retelling of Wyatt’s arrest, conviction, and incarceration, told from her own shoe-gazing point of view. It starts with an absolutely gorgeous line worthy of Billy Bragg’s “Milkman of Human Kindness,” but then immediately snatches it back, mirroring the expectations of one who lives on the shady side of the street:

Hello, neighbor. Are you hungry? Are you screaming out for love?

‘Cause something tells me that you’re likely to stick me up.

Don’t be mistaken, I’m a pirate. I’m a thief from way back.

And all this time I was just trying to get my money stacked.

“Everyone is hungry in jail,” Wyatt says. “The food sucks. Everyone is kicking drugs, facing massive time in prison, sitting in fear, and dealing with years of trauma. My experiences have led me to see the darkest depths of humanity, where humans are animals, killing and conniving for drugs and money and the worst in jail. People wanna punk you, get you high, kick your ass, or con you out of a top ramen constantly.”

Despite the bleak outlook, the chorus makes light of the situation:

Time holds still at the Stone Hotel.

Three free meals on the county bill.

Takes my calls at the Stone Hotel.

Might be forsaken for now,

But I got someone waiting on me.

I’d always taken that last line as redemptive, as in she might be alone, but she’s got something, specifically someone to look forward to on the outside. Yeah, no. When I finally asked Jaime about it, she slapped that shit right down. Yup. Homonyms’ll get you every time.

“No one was waiting for me when I got out of jail, except maybe my mother,” she said with a laugh. “My greatest love to this day has been with drugs and alcohol. It just seemed like a cheeky way to convey the intense struggle and despair of imprisonment and condemnation. I try to undersell such things. So I was really making a joke that the cops were waiting on me hand and foot—taking my calls, preparing my meals, and even doing my laundry. Of course, it was only in trade for my dignity and freedom.”

The cover “Misery and Gin” closes out the collection. A sedate barstool lamentation, it was originally written by John Durrill for Merle Haggard, whose version was included in the 1980 Clint Eastwood feature “Bronco Billy.” Now, I understand that the late 70s and 80s were a hard time for most of the old outlaws, but the plain truth is that Jaime’s version is much, much better. Haggard’s take is full of Nashville overproduction and delivered with all the emotional resonance of a man reading the ingredients on his cereal box. With the authenticity of one who’s occupied that barstool herself, Wyatt delivers a glorious vocal performance, finding the soul of a legitimate old-school outlaw song that needed a little redemption itself.

She even makes a subtle but beautiful change in the lyrics while rearranging the genders:

Light a lonely cowboy’s cigarette

And we start talkin’ about what we wanna forget.

His life story and mine are the same.

We both lost someone and only have ourselves to blame.

By replacing the original “woman” with “cowboy,” she adds a little flourish of atmosphere that does the song a service. Great songwriting—and performance—is in the details.

So, who the fuck is Jaime Wyatt? Damned if I know. She’s one of the most intriguing people I’ve met in a business that tends toward intriguing people, but everything I learn about her only fuels more inquiry. What I know for sure is she’s a damn good person who’s been through a whole hell of a lot most of us can relate to, whether or not we share similar biographies. Combined with a tremendous reservoir of innate talent, those experiences have molded her into a frank, gripping songwriter and an emotive, captivating performer, and those features shine on Felony Blues. One of these days her dice might come up snake eyes, but Jaime Wyatt is a survivor and I’m betting she’ll shoot that eight the hard way.

tldr: Who the fuck is Jaime Wyatt? Who the fuck cares? Felony Blues is real country at its best.

Originally published by No Surf Music