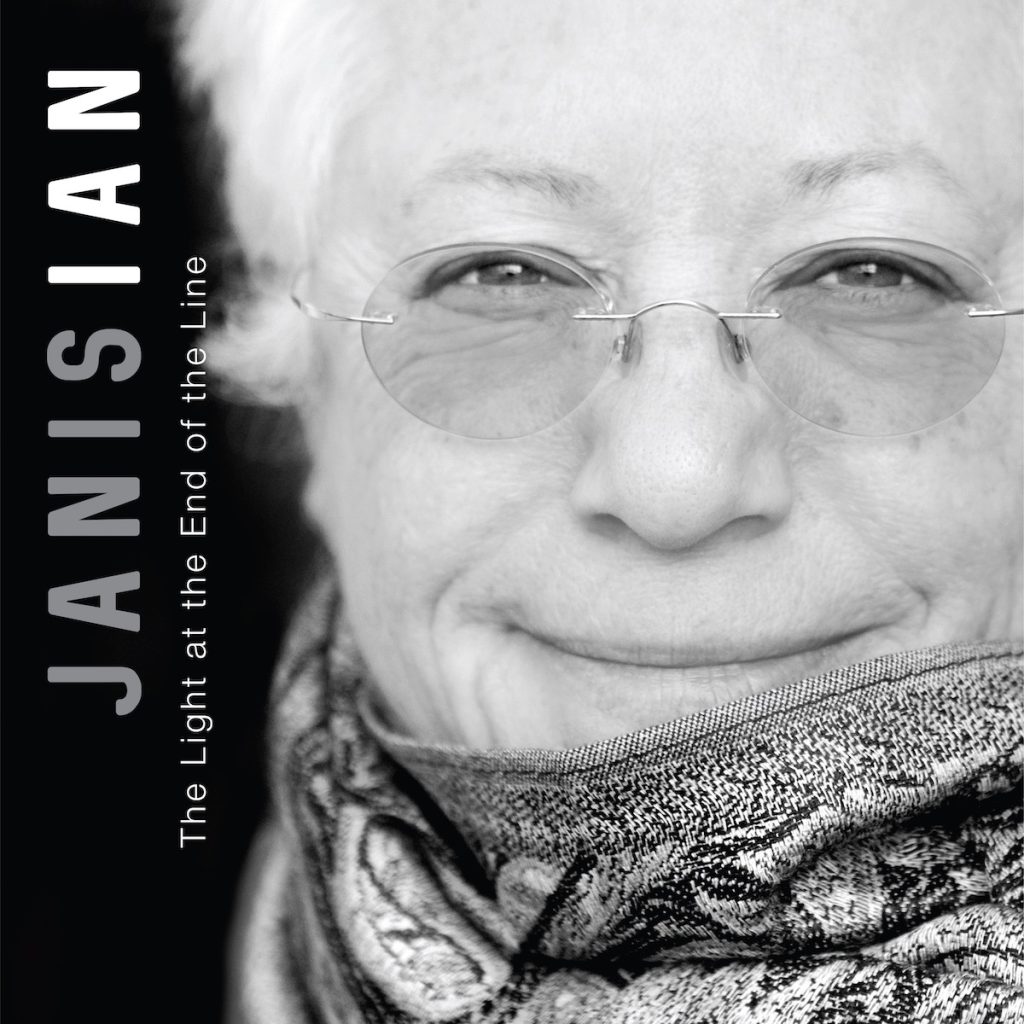

Janis Ian Affirms Her Legacy with ‘The Light at the End of the Line’

With The Light at the End of the Line, her first collection of new material in 15 years and, apparently, her farewell project, Janis Ian moves seamlessly between activistic declarations and descriptive verse, her melodies crystalline, her voice imbued with hard-won wisdom.

On the album’s guitar-and-vocal opener, “I’m Still Standing,” Ian acknowledges the ineluctability of death (“Every story I begin / just means another end’s in sight”) while celebrating her own resilience (“See these lines on my face? / They’re a map of where I’ve been”). At the song’s conclusion, she repeats the title line three times, each delivery infused with infectious chutzpah, her voice sounding increasingly triumphant.

The more fully instrumented “Resist” brings to mind the pop-oriented palette of 1995’s underrated Revenge. Lyrically, Ian resumes a commentary that she has embraced since the beginning of her career (most popularly with “At Seventeen” from 1975’s Between the Lines), cataloging myriad ways in which women are educationally, vocationally, and sexually oppressed. In a notably searing couplet, she proclaims, “Put her in high heels so she can’t run / carve out between her legs so she can’t come.” Randy Leago’s drum part, gravelly guitar, and Leslie-inspired synths forge a roadhouse-ready blues vibe, Ian’s voice towering over the mix.

While “Resist” directly confronts the toxic effects of patriarchy, “Perfect Little Girl” addresses the reality of gender-based inequality in more oblique fashion. The singer is presumably an older woman encouraging a younger one, assuring her that despite her struggles she “will find [her] season too.” “Stranger,” replete with Ian’s moody vocal, shimmering acoustic guitar, and empathic message re: the life of an immigrant circa the Trump era, illustrates Ian’s role as a vital bridge artist, how early in her career she absorbed and reconfigured the zeitgeist of the American folk revival and early 1960s songbook, in turn influencing a subsequent generation of neo-folk songwriters.

On the portentous “Dark Side of the Sun,” Ian interprets the relationship between God and the fallen angels of Genesis, as well as postlapsarian human life, her lyrics effusing a doomsday tone (“It doesn’t seem so far to fall / when you are up there, looking down / but from the ground you see eternity / and a distance so profound”). Ian’s guitar sounds bass-y, as if the strings are tuned down a half or whole step, her voice slightly strained (it would be interesting to hear Emma Ruth Rundle or A.A. Williams cover this tune).

While “Nina” is a lyrical tribute to the iconic musician Nina Simone, “Summer in New York” is an unabashed aesthetic tip of the hat, Ian’s piano part alternately staccato and fluid, her vocal performance simulating Simone’s effortless transitions from muted rage to tenderness, aggression to vulnerability. The album ends with “Better Times Will Come,” a bluegrassy cut perhaps prompted by Stephen Foster’s 1854 classic “Hard Times Come Again No More.”

If The Light at the End of the Line is indeed Ian’s final release, she retires on elevated ground, affirming her stylistic and perspectival legacies while exhibiting once more how she has continued to evolve artistically and, more importantly, as a human being.